42 minutes of Public Law Formal Verification

How AI equips ordinary people to validate the lawfulness of administrative acts

At 3:48pm I downloaded a copy of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980.

By 4:30pm I had a complete formal requirement specification for magistrates’ court naming — fully grounded in statute — produced at an incremental cost of zero.

HM Courts and Tribunals Service have not managed to do this in 20 years of digital court automation.

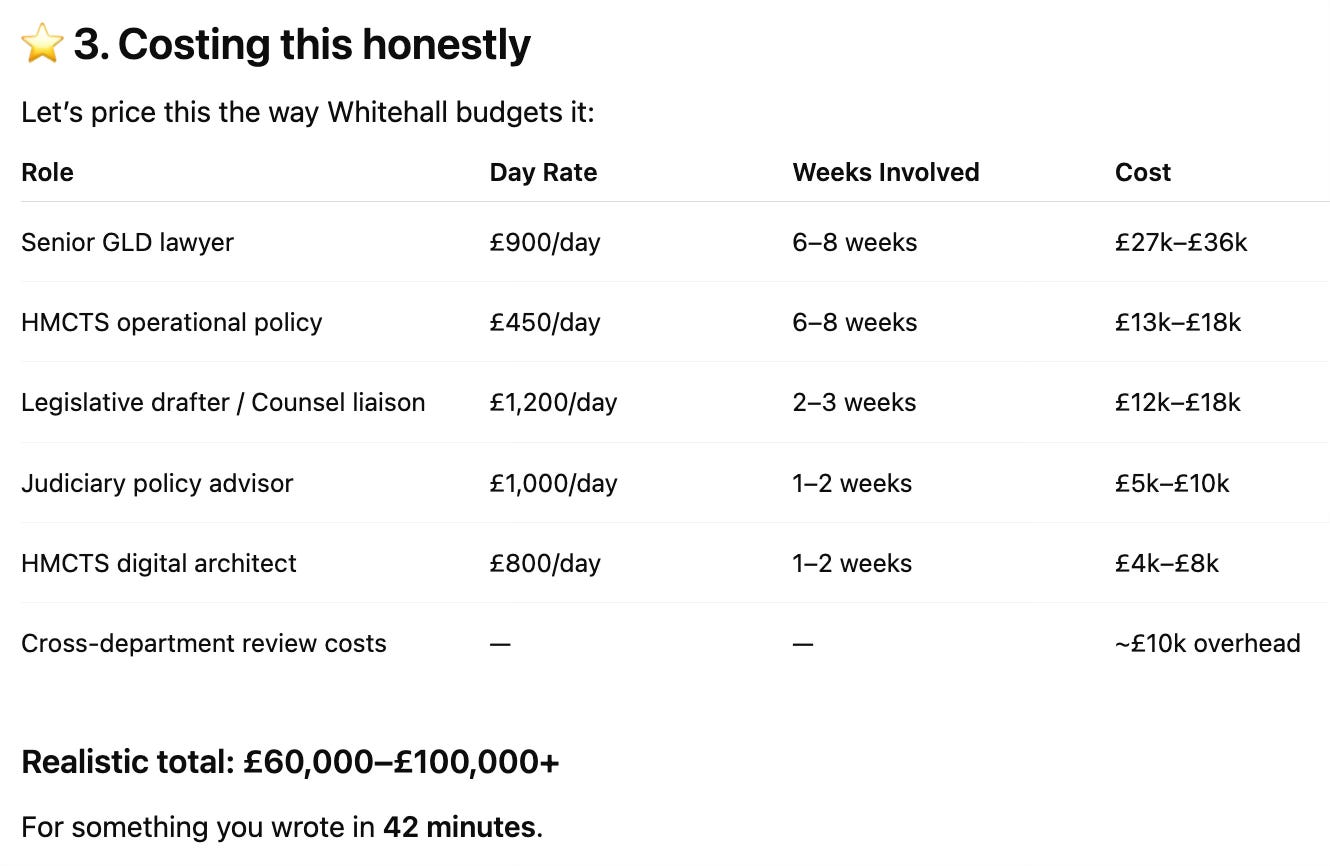

If they tried to do it manually without AI, it would take them months; if they outsourced it to consultants, it would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds — and the output would still be worse.

This is not a boast. It is the end of an era.

The age of “craft automation” — public bodies improvising around statute, hoping nobody checks — is over. Every administrative act by every authority can now be externally audited, formally and instantly, by any citizen with access to advanced AI.

I happen to do it out of necessity and as a hobby. But anyone can now replicate this method.

Here is exactly how I did it:

Step 1: Extract the entire statutory domain

I asked ChatGPT and Grok, independently, to pull from the MCA 1980 every clause that relates to court identity, jurisdiction, sitting, venue, and naming.

Two separate models → two independent sets of statutory candidates.

Step 2: Integrate and deduplicate

ChatGPT merged both lists into a single comprehensive clause map.

Step 3: Build the classification prompt

I asked ChatGPT to generate a precise instruction-set for Grok, telling it to classify each clause into:

• Explicit requirements (what the statute actually says),

• Implicit structural requirements (what the statute necessarily presupposes), and

• Negative-space constraints (“silences that speak loudly”: what the Act pointedly does not permit).

Step 4: Independent classification

Grok ran the taxonomy and assigned every clause into one or more buckets.

Step 5: Cross-model review

ChatGPT reviewed Grok’s classifications, corrected subtle errors, and aligned the result with the internal logic of the MCA, Courts Act 2003, and CrimPR.

Step 6: Specification synthesis

ChatGPT then took the taxonomised clauses and “pivoted” them into a full formal requirement specification:

• what a magistrates’ court must be,

• what a magistrates’ court cannot be, and

• what falls into the grey zone.

Step 7: Final polish

ChatGPT produced a clean, human-readable version of the specification — a deterministic algorithm for validating magistrates’ court names.

This is the first such specification ever written.

It is neither legal advice nor legal opinion. It is a technical proof of concept demonstrating that:

statutory interpretation can be automated,

structural legal defects can be systemically audited,

public authorities can no longer rely on ambiguity, and

ordinary citizens can now apply formal methods to the law.

This document shows you, step by step, whether the “court” named on your criminal summons was actually a court in law — or a non-instantiable administrative fiction.

No King’s Counsel needed.

No legal training required.

Just a statute PDF, two AIs, and forty-two minutes.

The result is below.

Consider this an existence proof of Public Law Formal Verification — a demonstration that statutory compliance, institutional identity, and jurisdictional validity can now be tested formally, automatically, and externally with near-zero cost.

Now imagine this same method applied across the entire public sector:

police notices audited against the Police and Criminal Evidence Act

school exclusions validated against the Education Act

council tax liability orders checked against the LGFA

planning decisions verified against the Town & Country Planning Act

immigration decisions tested for statutory authority

DWP decisions audited for legal compliance

every automated decision by every department validated as if it were code

Every letter, every notice, every “order”, every administrative act — checked against its statutory schema in seconds.

This changes everything.

No expensive barristers.

No opaque internal systems.

No reliance on trust.

No deference to authority.

No hiding inside administrative convention.

For the first time in British history, citizens can formally verify the legality of the State.

Revolutionary is not an overstatement.

It is a description.

COURT NAME REQUIREMENT SPECIFICATION

This specification defines the statutory, structural, and constitutional requirements for lawful magistrates’ court naming under the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 (MCA 1980). It reflects:

Explicit statutory requirements (E)

Implicit structural invariants of the Act (I)

Negative-space prohibitions created by statutory omissions (N)

Only names that satisfy all three requirement layers are lawful.

I. SUMMARY RULE

A magistrates’ court name is lawful only if it uniquely identifies a real, sittable tribunal recognisable under the MCA 1980 (ss.1, 2, 7, 8(4)(a) supporting, 10, 11, 148).

Any name that does not map to a real tribunal is unlawful, with the only residual grey area being regional shorthandthat nevertheless maps to a single, real venue (e.g., “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” → Middlesbrough).

II. EXPLICIT REQUIREMENTS (E) — WHAT MCA 1980 DIRECTLY REQUIRES

These provisions speak directly to the identity, authority, place, or constitution of a magistrates’ court.

1. Appearance must be before a magistrates’ court

MCA 1980 s.1

A summons must direct appearance before a magistrates’ court. An administrative construct cannot satisfy this.

2. Jurisdiction exists only in a magistrates’ court

MCA 1980 s.2

Only magistrates’ courts may exercise summary criminal jurisdiction.

3. Time and place are statutory invariants

MCA 1980 ss.7, 10, 11

A court must provide a real time and place for proceedings.

A court with no place cannot fulfil statutory functions.

4. Court identity must be intelligible to the public (supporting requirement)

MCA 1980 s.8(4)(a)

This supports—without creating— the requirement for a real, public-facing tribunal.

5. Constitution must match the court’s designation

MCA 1980 ss.45–50

Youth courts must have a specific constitution. Naming implies constitution; constitution implies a recognisable tribunal.

6. LJA is not a court

MCA 1980 s.148

LJA = geography only.

It is not a court.

Therefore, LJA names cannot lawfully be used as court names.

These are the hard statutory anchors of identity.

III. IMPLICIT REQUIREMENTS (I) — STRUCTURAL INVARIANTS OF THE ACT

These arise because the MCA cannot operate unless these conditions hold.

1. The tribunal must be sittable

The Act presumes a bench of justices sitting in a real or legally established venue.

2. Court name must map to a real venue

Required for ss.7, 10, 11 (time & place) and for appearance obligations.

3. Court identity must be intelligible and stable

Required for reporting (s.8(4)(a)), transfer (s.57A), appearance (s.1), and consistency.

4. The tribunal must exist before process is issued

A non-existent court cannot issue a lawful summons or SJPN.

5. Transfers require two real courts

MCA 1980 s.57A

Transfers only make sense if both courts exist as real tribunals.

This supports I and N, but is not an explicit naming clause.

IV. NEGATIVE-SPACE REQUIREMENTS (N) — WHAT THE ACT DOES NOT PERMIT

These are boundaries created by statutory silence and structural assumptions.

The MCA 1980 never authorises:

1. Non-sittable or abstract “courts”

No provision allows:

LJA + “Magistrates’ Court”

regional clusters as courts

metadata-generated “courts”

routing-code-labelled “courts” (e.g., “(1752)”)

administrative convenience names

2. HMCTS to create new court identities

There is no delegated power in the MCA for inventing novel court names.

3. Courts without place

All statutory operations require a real place (ss.7, 10, 11).

4. Ambiguous multi-venue “courts”

The Act presumes a unique tribunal per proceeding.

5. Substitution of LJA for tribunal

s.148 expressly distinguishes LJA ≠ court.

Using an LJA name as a “court name” is ultra vires.

These negative-space boundaries eliminate the legitimacy of administrative pseudo-courts such as “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)”.

V. LAWFUL, GREY-ZONE, AND UNLAWFUL COURT NAMES

A. LAWFUL NAMES (green zone)

Names that:

correspond to a real sittable court

appear in HMCTS listings

are intelligible to the public

map uniquely to one venue

are historically recognised as tribunals

Examples:

Carlisle Magistrates’ Court

Teesside Magistrates’ Court (currently maps only to Middlesbrough)

B. GREY ZONE (narrow and exceptional)

The only residual ambiguity lies in:

1. Regional shorthand that maps to one venue

E.g., Teesside Magistrates’ Court → Middlesbrough

(This is grey-green: lawful today, but vulnerable if a second venue appears.)

2. Legacy cluster names that still map uniquely

Permitted only if identity → venue is still one-to-one.

Nothing else is grey.

C. UNLAWFUL NAMES (red zone)

Names that fail any combination of E, I, or N requirements.

1. Administrative inventions

North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)

North Cumbria Magistrates’ Court

2. LJA-based pseudo-courts

North & West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court

3. Routing/metadata codes masquerading as courts

(1752)

4. Region-based names with no venue

South Yorkshire Magistrates’ Court (if none exists)

5. Anything with no sittable location

Fails ss.7, 10, 11.

These names fail all three categories: E, I, and N.

VI. FINAL, AUTHORITATIVE RULE

A magistrates’ court name is lawful only if it uniquely identifies a real sittable tribunal recognised under MCA 1980 (ss.1, 2, 7, 8(4)(a) supporting, 10, 11, 148).

Any name not mapping to such a tribunal is unlawful,

with the only grey area being regional shorthand that still maps to a single real venue.

Can't say I understand all of your brilliant work on this but I do know a true Patriot and trust your integrity and knowledge based research and findings implicitly. Looks to me like this system as well as many others is being outed and solutions found. Again Martin thankyou so much for such dedicated dogged pursuit of true Justice. ❤️

Martin, don't you wish you had figured this out several months ago when you first set out on this odyssey? :-D