A doctrine of curability in court naming

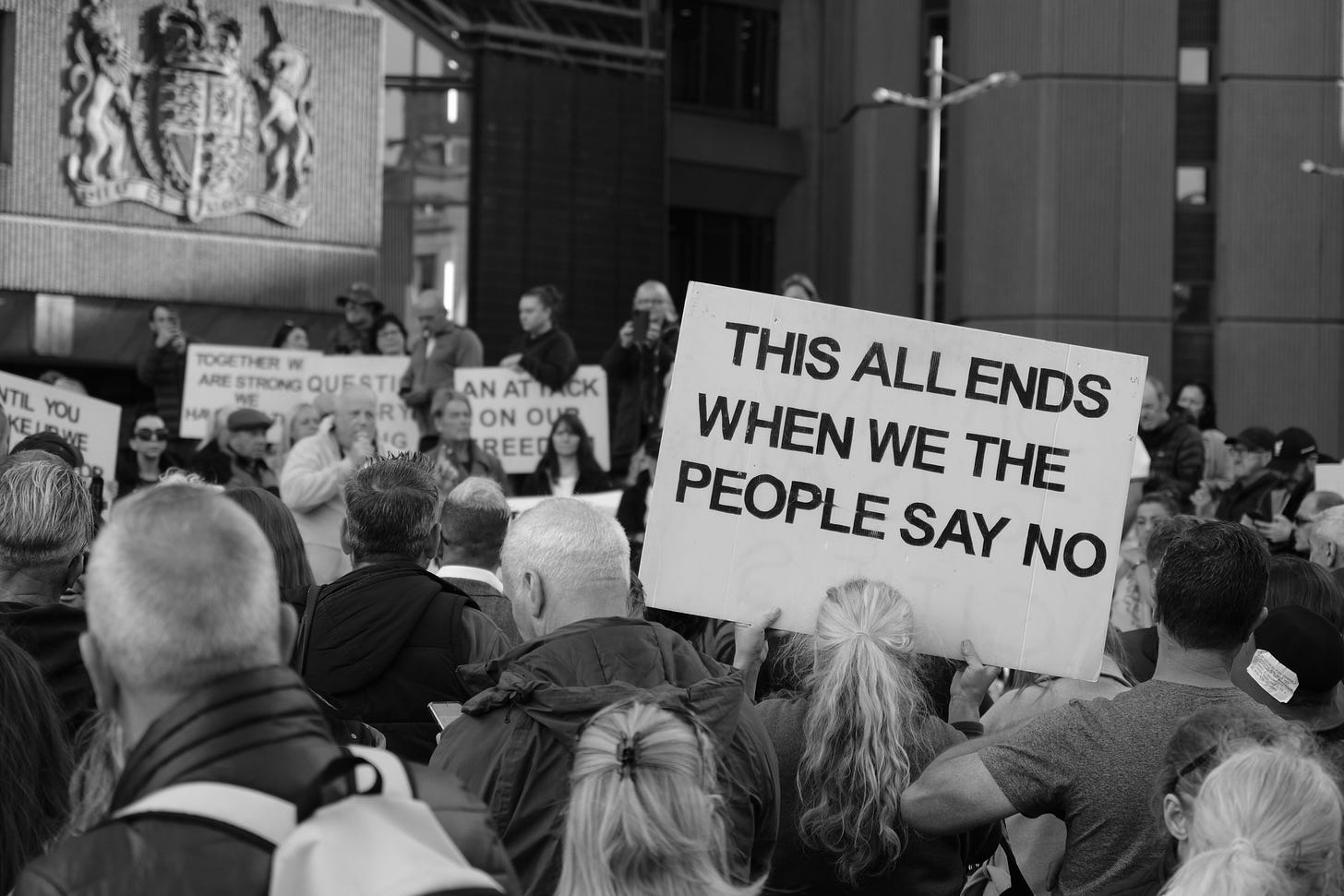

Demonstrating how a litigant-in-person, equipped with AI, collapses the legal profession’s gatekeeping and audits the State’s compliance with its own rules

For years, Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service has processed millions of cases under the Single Justice Procedure using what are now acknowledged to be “ghost courts” — tribunals not known to law. The State’s defence amounts to a series of hand-waves:

judges can wave a magic wand over any defect,

magistrates are like Uber drivers,

court names are decorative clip art,

so long as you can find the building on Google Maps you’ve had a fair trial,

and if all else fails, the High Court can bless yesterday’s fraud as today’s law.

Set against this bureaucratic improv, the doctrine presented here is conservative in the best sense: rooted in centuries of precedent, animated by the rule of law, and framed to preserve fairness rather than to invent novelty. It insists on a simple but unforgiving principle: the name of a court on a summons is a truth-claim to authority. If that claim is false, the process is void.

No fairy dust, no holy sacraments — just law, as Blackstone would have recognised it and as Article 6 of the ECHR still demands. The framework itself has taken only a week or two to shape, but it rests on a lifetime of systems thinking, leaning heavily on my computer science background — the same mindset that tells us garbage in means garbage out, and that a type error at root will always crash the system.

While the content itself matters — millions of convictions and billions of pounds are potentially at stake — it also signals something larger. I have never been on a law course in my life (I never even formally learned to type), yet the barriers to participation in the upper echelons of jurisprudential reasoning have collapsed. That means the monopoly of lawyers, judges, and officials on defining justice is broken.

If one outsider can expose this void, then anyone can audit the state’s claims to authority — and the system will never be the same again.

This is a working draft, offered into the public square. I would welcome feedback.

Definitions

Juridical Root Entity: A tribunal constituted by statute or statutory instrument, with authority tethered to a warrant of establishment (e.g., Courts Act 2003, SI defining LJAs). Ad hoc or hybrid constructs do not qualify.

Curability Floor: The minimum threshold below which naming errors render process void ab initio. Below this floor, there is no tribunal established by law, and nothing to cure.

Intentional Void: A naming failure by misrepresentation, where the description positively asserts a fictional tribunal. Misleads rather than falls short. Constitutionally incurable.

Denotational Void: A naming failure by omission, where the description does not fully denote the lawful tribunal but gestures towards it. Inadequate, technically void under strict reading, but tethered to something real. Potentially curable (or retrospectively regularisable by Parliament).

Operational Void: A jurisdictional failure where, notwithstanding lawful denomination, the tribunal in practice does not operate as established by law. Examples include failure of justices to sit, automated issue without judicial involvement, or breach of Article 6 standards. The machinery of process itself is void.

Anti-Logos Name: A name which, by its very form, obscures or falsifies the lawful warrant of a tribunal. Such a label is anti-truth and therefore void ab initio, beyond any statutory cure.

Logos Principle: The Logos is the covenant of law itself: the lawful word through which authority flows, however imperfectly. Without Logos, jurisdiction collapses, for the court’s claim to authority ceases to be anchored in truth. This reflects the rule of law principle in UNISON [2017] UKSC 51 (Lord Reed, [68]) and the ECHR requirement of certainty in DMD Group v Slovakia (2010) [60–65].

1. Case Law Precedents

Anisminic v FCC [1969] 2 AC 147 – Fundamental jurisdictional errors render decisions null; cannot be cured.

R v Manchester Stipendiary Magistrate ex p Hill [1983] AC 328 – Composition/timing errors only curable if tribunal identity remains intact; wrong type or jurisdiction is fatal.

R v Cripps ex p Muldoon [1984] QB 686 – Distinguishes between curable errors of expression and incurable substantive defects.

R v Lam [1999] 163 JP 409; Harlow Justices [2004] EWHC 296 (Admin) – Summons naming non-existent courts are void ab initio, beyond statutory cure.

Bradford Justices ex p Sykes [1999] COD 198 – Summons must provide sufficient detail to identify lawful tribunal; otherwise incurable.

Argos Ltd v OFT [2006] EWCA Civ 1318 – Curability depends on whether procedural defect affects substantive fairness; authority clear vs overreach void.

R (Parashar) v Sunderland Magistrates’ Court [2019] EWHC 927 (Admin) – Minor slips in magistrates’ process curable if no prejudice.

R (Privacy International) v IPT [2019] UKSC 22 – Jurisdictional error cannot be ousted; tribunal acting beyond remit is void.

Majera v SSHD [2021] UKSC 46 – Procedural defects can be cured purposively if statute so intends and no prejudice arises.

R (L) v SSJ [2008] EWCA Civ 97 – Confirms safeguards around LJA boundaries.

Boddington v British Transport Police [1999] 2 AC 143 – Affirms collateral challenge where jurisdiction is questioned.

2. Statutory and Procedural Anchors

Courts Act 2003, s.1 – Magistrates’ courts exist only as statutory creatures.

Courts Act 2003, s.8 – Local Justice Areas (LJAs) define jurisdictional basis.

Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980, s.123 – Defects may be amended if no prejudice; does not extend to non-existent tribunals.

CrimPR 7.2–7.4 – Summons must identify the issuing court clearly.

CrimPR 24.4 – Powers to amend at trial.

CPR 3.10 – Civil courts’ general power to rectify errors.

Contextual Differentiation:

Criminal: Higher prejudice threshold. Liberty at stake requires strict compliance. Summons naming void courts incurable (Harlow).

Civil: Greater flexibility. CPR allows broad rectification if no prejudice (e.g., slip rule in judgments).

3. Frameworks from Authority

Necessary vs Sufficient Certainty: Both required for curability.

Type Invariance: Court type cannot change (e.g., Magistrates → Crown) by cure.

Root vs Leaf Errors: Root errors (juridical identity, jurisdiction) void; leaf errors (typos, clerical) curable.

One-to-One Mapping: An erroneous name must collapse cleanly into one lawful referent. Ambiguity defeats curability.

Surplusage Rule: Extra words can be ignored only if core identity remains tethered to a lawful tribunal.

4. Maxims

Falsa demonstratio non nocet, cum de corpore constat – False description does not vitiate, if corpus certain. So what? Minor slips are tolerable if the real court is clear; but if the corpus is uncertain, the converse applies—jurisdiction is void.

Id certum est quod certum reddi potest – That is certain which can be made certain. So what? Shorthand may be cured if it collapses cleanly to a lawful tribunal.

Ex nihilo nihil fit – Nothing comes from nothing: void cannot be cured into jurisdiction. So what? A ghost court name creates nothing at all; it cannot be salvaged.

Ubi jus incertum ibi nullum – Where the law/identity is uncertain, there is no law. So what? Ambiguous court names (e.g., ghost constructs) cannot ground jurisdiction.

Contra Logos nulla potestas – Against truth, no authority. So what? A false or anti‑Logos name strips the process of lawful power.

Principium robustum (lex) – Accept broadly, emit narrowly: the state may be liberal in what it accepts from the public, but must be conservative in what it emits as authority. So what? Citizens’ slips may be forgiven; state misnaming (ghost courts) is fatal.

5. Under- vs Over-Specificity

Under-specific (Denotational Void): e.g., “Carlisle MC”. Incomplete, fails to finish the name, but tethered to the real LJA tribunal. Technically void, but potentially curable or retrospectively regularisable.

Over-specific (Intentional Void): e.g., “NWCMC1752”. Misrepresents the LJA as if it were a corporate tribunal, compounded by IT coding. This is misleading, not merely incomplete, and is incurable.

Correct Form: “The Magistrates’ Court for the [LJA]” is the only formula that avoids both under- and over-specificity.

6. Misrepresentation Dimension

Where HMCTS have acknowledged non-use of juridical names, this amounts to systemic misrepresentation rather than an innocent slip.

Ex p Smith [1991] and Three Rivers [2003] UKHL 48 highlight that concealment of jurisdictional truth aligns with misfeasance in public office.

Transparency principles (R (Corner House) v SFO [2008] UKHL 60; R (Miller) v PM [2019] UKSC 41) reinforce the duty to name real tribunals accurately.

Boddington [1999] confirms collateral challenges may be raised where jurisdiction is defective.

Ministerial correspondence in 2025 admitted certain “courts” (e.g., “North Cumbria Magistrates’ Court”) were not known to law. Public reports (BBC, Aug 2025) revealed IT mislabelling leading to missing evidence in thousands of cases. These illustrate systemic misrepresentation.

7. Comparative Analogies

Corporate Misnomer Cases: Minor slips (Ltd vs PLC) curable; naming a non-existent company void (Davison v Stenning [1895] 1 QB 48).

Companies Act Disclosure Floor: Companies must display true name, number, jurisdiction. Failure is a criminal offence. By analogy, HMCTS must not fall below a similar disclosure floor in naming courts.

8. Robustness Principle for Law

Rule: Be accepting of broad input; be narrow in what you emit.

Public → State (Input): Where a defendant or lay party misdescribes a tribunal but clearly intends the lawful LJA court, that denotational void may be cured (MCA s.123; Sykes), absent prejudice.

State → Public (Output): When HMCTS/CPS name a tribunal on an instrument, they make a truth-claim to authority. Their obligation is higher: output must meet the high quality floor (LJA-tethered, non-misleading). Any intentional void or anti-Logos designation is per se null.

Justification: Principle of legality, fair notice, Article 6 ECHR (“established by law”), and asymmetry of power. The burden of clarity lies with the state.

Analogy: Inverted Postel’s Law: tolerate imprecision from citizens; forbid it by the state.

9. Computer Science Analogies

Separation of Concerns: Juridical authority (root) must be distinct from administrative labels (leaf). Example: An IT code “1752” may exist internally, but if printed as a court name, the summons is void.

Fail-Fast Principle: Misnaming at the root is immediately fatal. Example: “NWCMC(1752)” should void process at issue stage.

Garbage In, Garbage Out (GIGO): A fictitious court name poisons all subsequent proceedings.

Type Safety / Invariance: A magistrates’ court cannot be retyped into a fictional tribunal. Such type errors are void ab initio.

Determinism / Idempotence: A valid designation must always resolve to the same lawful tribunal. If it produces multiple or shifting referents, jurisdiction fails.

Doctrinal Ratio

Errors in court naming are only curable where the description necessarily and sufficiently denotes a tribunal established by law. Orthographic and leaf errors are amendable under statutory or procedural rules. Root errors — wrong type, fabricated entity, anti-Logos naming, or systemic misrepresentation — are void ab initio.

Within this framework:

Intentional Voids (over-specific): misleading, fabricating entities → incurable nullities, beyond statutory cure.

Denotational Voids (under-specific): inadequate but tethered to something real → potentially curable, including under s.123 MCA.

Operational Voids: where, notwithstanding correct denomination, the tribunal fails in practice to operate as established by law. Examples include summonses generated without judicial involvement, courts failing to sit, or procedures breaching Article 6.

Anti-Logos Names: any name that obscures or falsifies the tribunal’s lawful warrant is automatically void, as it negates the truth-claim to authority.

Logos Principle: The Logos is the covenant of law itself: the lawful word through which authority flows. Without Logos, jurisdiction collapses, for the court’s claim to authority ceases to be anchored in truth.

The name on a summons or order is a truth claim to authority. If false, it misleads; if denied as a claim, no authority is asserted. The doctrine therefore requires a disclosure floor: authority must be declared, not simulated. Where misdescription is systemic, defects are presumptively intentional voids. Parliament may cure omissions by deeming shorthand sufficient, but it cannot conjure new courts into existence retrospectively. By analogy with company law, statutory fidelity is required: nothing can be cured from non-existence.

Conceptual Flowchart

Does the name denote a tribunal established by law?

No → Void ab initio (Anisminic).

Yes → Go to step 2.

Is the tribunal type preserved (type invariance)?

No → Void (Hill).

Yes → Go to step 3.

Is the error root or leaf?

Root (juridical identity, hybrid entity, misrepresentation, anti-Logos name, operational failure) → Void (Harlow, Privacy International, Three Rivers).

Leaf (typo, surplus word → Denotational Void) → Curable (Sykes, MCA s.123).

Is there prejudice to parties?

Yes → Void (Majera, Art 6 ECHR).

No → Curable.