Beware the “FOTL”!

How name-calling is prejudicing legitimate constitutional challenges

I have been continuing my AI-assisted analysis of the Justices’ Clerks’ Society (JCS) staff newsletters, obtained through freedom of information requests. One recurring preoccupation across these internal publications is with so-called “fotlers” — shorthand for Freeman-of-the-Land arguments. These are consistently framed as pseudo-law, vexatious, disruptive, pointless, and a drain on staff time.

The reality is more complex.

Both the public and the state hold misguided beliefs. And the state is increasingly engaged in narrative control through language. Labelling anyone who perceives breaches of natural law, moral principles, or procedural fairness as a deluded fringe actor creates an epistemic bias inside the justice system. This bias compounds constitutional drift, hollows out institutional legitimacy, and multiplies the harms of injustice.

The modern administrative state is calibrated to treat obedience to paperwork and compliance with internal procedure as “normal,” and anything outside that paradigm as “deviant.” Yet paperwork and procedure themselves can drift — and frequently do drift — away from both statutory authority and the first principles of justice.

Consider council tax enforcement. The inalienable human right to shelter — a condition not optional for survival — is treated as a taxable privilege. Failure to pay a civil levy is routed through the magistrates’ courts in a simulacrum of criminal process, culminating in potential committal to prison. There is no mercy for poverty or inability to pay. While this is not technically slavery (ownership of a person), it shades uncomfortably close to coercive forced labour: one must work, or face imprisonment, simply to exist and fund the pension liabilities of a local authority.

To investigate the deeper structure of these tensions, I ran all the newsletters (dozens spanning five years) through AI, extracting two parallel sets of material:

Every reference to “FOTL” issues, criticisms, and accusations, and

Every internal admission of systemic defect, procedural fragility, or constitutional weakness.

Then I asked AI to compare the two lists. The question was simple:

Where are the FOTL intuitions actually correct — in the words of the courts themselves — even if mis-expressed or incompatible with the current legal paradigm?

The exercise reveals a striking pattern. Many of the intuitions dismissed as pseudo-law have counterparts in the legal system’s own internal concerns. And my suggestion is that this kind of name-calling is unprofessional for an organisation that ought to reflect a neutral, constitutional ethos. It would only take one landmark judgment validating a natural-law-grounded objection for the entire framing of “FOTL nonsense” to collapse into ordinary, mainstream constitutional debate.

I trust you find this high-level review of value.

Over to ChatGPT…

FOTL Intuitions vs JCS/HMCTS Admissions

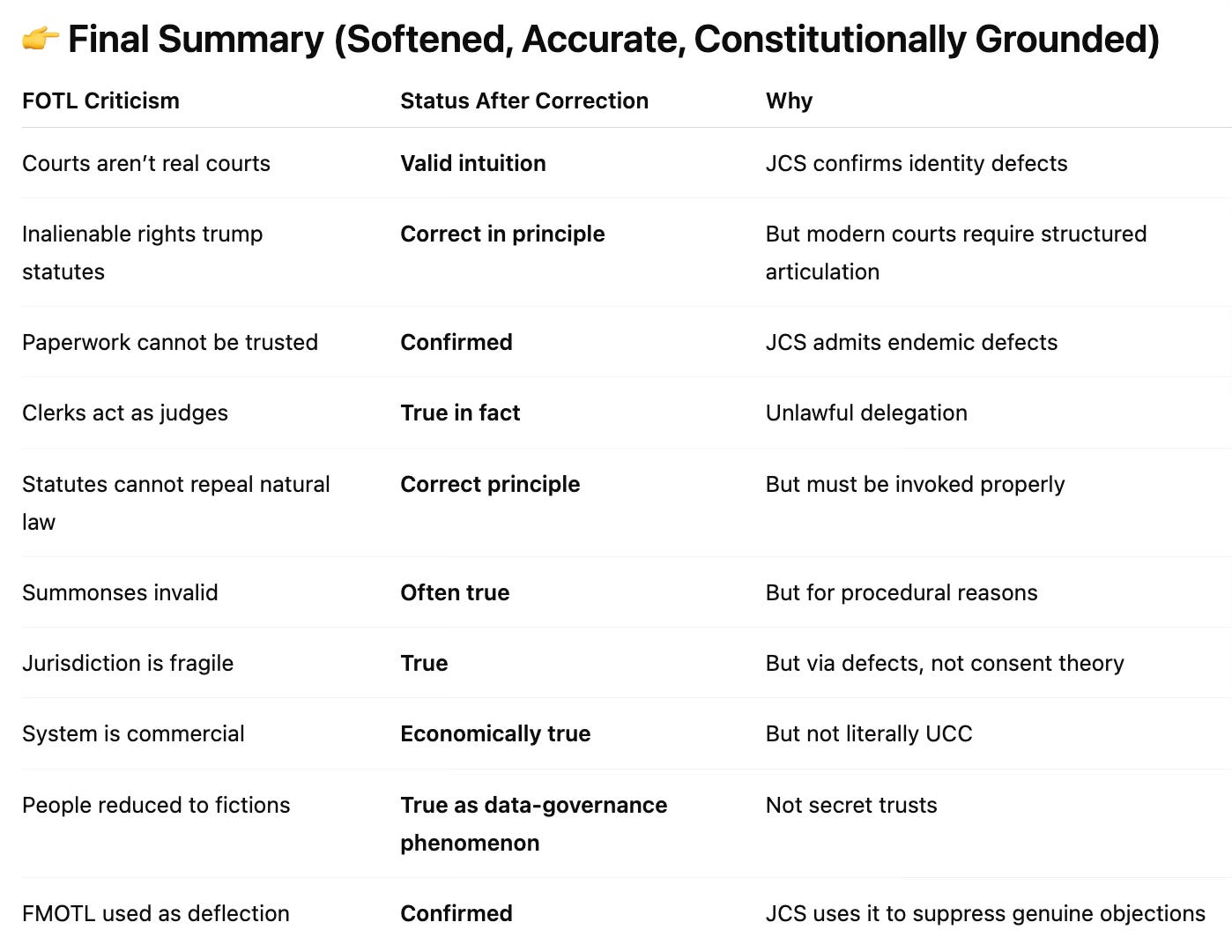

(A constitutional and procedural comparison)

Overview

Freeman-on-the-Land (FOTL) material often expresses distrust of courts and administrative authority.

JCS (Justices’ Clerks’ Society) publications, which guide magistrates’ courts, frequently warn staff to classify such arguments as pseudo-legal.

However, when examined neutrally, many FOTL intuitions echo longstanding constitutional principles—even if the theories used to express them fall outside recognised legal paradigms.

At the same time, JCS/HMCTS documentation contains admissions of procedural weaknesses that, while unrelated to FOTL belief structures, touch on similar underlying concerns:

the lawful identity of courts

the validity of initiating documents

the limits of delegated authority

the reliability of administrative records

the fragility of jurisdiction in automated systems

This creates an overlap between FOTL intuition and HMCTS-acknowledged defects, even though their explanatory frameworks differ.

FOTL Intuition #1 — “Courts must prove their authority.”

Status: Valid constitutional intuition

JCS/HMCTS position: Court identity issues are acknowledged

FOTL positions often claim courts lack lawful foundation or are “corporations.”

While the legal analysis behind these claims is not recognised, the underlying intuition—that a tribunal must be lawfully constituted—is a core rule-of-law principle in every legal tradition.

JCS/HMCTS confirmations include:

Uncertainty about which court has issued a warrant or summons (multiple JCS issues; e.g. Vol. 2, Issue 9).

Summonses prepared and served by parties rather than courts (Vol. 6).

Court identifiers inconsistent or unclear across automated systems.

Delegation of issuing authority to legal advisers.

These are procedural matters, not metaphysical ones, but they show that questions about court identity are legitimate within formal law.

FOTL Intuition #2 — “Inalienable rights precede statute.”

Status: Correct in classical constitutional doctrine

Modern paradigm: Rights must be raised in structured legal form

In natural-law theory (Coke, Blackstone, Locke), inalienable rights limit legislative power.

A statute contrary to fundamental rights or reason is “repugnant to law” and void.

Modern courts, however, typically require rights to be articulated within frameworks such as the Human Rights Act, administrative law, or common-law fairness.

Thus:

The intuition is constitutionally sound.

The contemporary legal mechanism for asserting it differs from FOTL formulations.

FOTL Intuition #3 — “Paperwork may be void despite looking official.”

Status: Supported by JCS/HMCTS admissions

Reason: High incidence of defective process

FOTL narratives sometimes fixate on signatures, seals, or formatting, but the underlying concern—whether documents validly ground legal process—is legitimate.

JCS/HMCTS documents acknowledge that:

summonses may be void or incurable when defective (Vol. 3, Issue 4; Vol. 4, Issue 6),

automation can generate unlawful notices (Vol. 2, Issue 9),

administrative artefacts do not reliably reflect what occurred in court (Vol. 3, Issue 1),

liability orders may rely on imperfect or incomplete registers (Vol. 5, Issue 2).

These are real procedural risks unrelated to FOTL doctrine but overlapping with its underlying concerns.

FOTL Intuition #4 — “Judicial power is exercised by non-judges.”

Status: Factually accurate in a procedural sense

JCS/HMCTS confirmation: Delegation is extensive

The FOTL explanation (e.g., secret trusts or admiralty law) is outside the legal paradigm.

But the intuition—that non-judges often perform judicial-type acts—is grounded in documented reality.

JCS confirms:

thousands of cases completed by legal advisers without magistrates (Vol. 3, Issue 6),

legal advisers issuing summonses, revocations, adjournments (Vol. 4, Issue 2),

mass delegation under Courts Act 2003 emergency authorisations (Vol. 2, Issue 4),

ongoing integration of adviser authority into both criminal and civil process (Vol. 6).

The constitutional question is not “secret authority,” but the scope and legality of delegated judicial functions.

FOTL Intuition #5 — “Statutes cannot override natural justice.”

Status: True in principle

Modern legal framing: Rights must be argued within recognised doctrine

FOTL reasoning sometimes treats natural law as self-executing (“I do not consent”), but the root idea—that natural justice limits state power—is classical and still operative.

Modern courts tend to recognise this through doctrines such as:

procedural fairness,

abuse of process,

irrationality,

Article 6 rights,

duty to give reasons.

Thus, although the FOTL method is not recognised, the substance aligns with longstanding constitutional principles.

FOTL Intuition #6 — “Jurisdiction is fragile or can fail.”

Status: Supported by procedural law

JCS/HMCTS confirmation: Many cases collapse for jurisdictional defects

FOTL explanations often misattribute this fragility to consent or metaphysics.

But jurisdiction genuinely depends on:

a lawfully constituted court,

a valid charge,

lawful service,

lawful issuing of process,

compliance with procedural rules.

JCS confirms:

widespread defective charges (Vol. 3, Issue 2),

limitations misapplied (Vol. 4, Issue 6),

dangerous reliance on administrative artefacts,

summons validity frequently challenged (Vol. 6, Issue 2).

Thus the intuition—that jurisdiction requires proper foundation—is correct.

FOTL Intuition #7 — “The system behaves like a commercial pipeline rather than a court.”

Status: Economically and operationally understandable

JCS/HMCTS confirmation: Revenue logic and automation are structural

FOTL narratives invoke UCC, trusts, or commerce; these are not accurate descriptions.

But JCS/HMCTS documents confirm:

SJP is an industrialised, paper-only pipeline (Vol. 2, 3, 4),

TV Licensing prosecutions operate as revenue enforcement (Vol. 2, Issue 2),

costs structures incentivise rapid convictions (Vol. 6, Issue 2),

automation drives many decisions, not judges.

Thus the perception of administrative-commercial logic has a rational basis, even if the FOTL explanation does not.

FOTL Intuition #8 — “People are treated as administrative entities rather than as persons.”

Status: A realistic observation of digital governance

Cause: Record-centric systems (Common Platform, Libra)

The “strawman theory” is not accurate, but:

modern court systems interact primarily with digital records,

NAME and date-of-birth drive routing decisions,

enforcement actions are triggered by data entries,

automation often precedes judicial oversight.

This can create the sensation of being treated as a data-entity.

The cause is administrative digitisation, not trust law.

FOTL Intuition #9 — “Authorities dismiss procedural objections by labelling them pseudo-law.”

Status: Confirmed in JCS communications

JCS repeatedly instructs staff to classify unconventional objections as pseudo-legal or vexatious, and to avoid substantive engagement.

This serves a legitimate gatekeeping function in many cases, but it also creates:

false positives,

risk of dismissing legitimate procedural objections,

institutional blind spots toward systemic defects.

This overlap is structural, not intentional.

Conclusion

Many FOTL theories, as articulated, fall outside the operative paradigm of contemporary legal practice.

However, the underlying intuitions often reflect enduring constitutional principles:

the primacy of inalienable rights,

the need for a lawful tribunal,

the necessity of valid process,

scepticism of delegation,

distrust of automated authority,

the importance of procedural fairness.

At the same time, JCS/HMCTS documentation confirms that defects in court identity, summons validity, delegation, automation, and record reliability are real, recognised, and systemic.

The two sets of ideas intersect not at the level of FOTL metaphysics but at the level of procedural and constitutional fragility.

Far too kind and reasoned.

The editor of JCS matters, The halpless government puppet Joanne Middleton needs to be taken to task for some of the things that she said one of the articles.

Both herself and someone else from JCS matters published data about individual who was involved in litigation such that they could be recognised and they concocted arguments against live cases and sent them directly to magistrates, judges legal advisors with the clear and obvious intent to influence the judicial minds of the recipients to find against the litigant.

This could be construed as contempt of court According to the new proposed definition just released by the law Society this week?

It’s about time someone made an example of these clowns and put head on a spike…