Courts of Convenience: From human honour to machine void

How "we have always done it this way" is half-true, and very problematic today

I have been digging into why HMCTS would attempt to justify the absurd: that court names don’t matter, court buildings don’t matter, Local Justice Areas don’t matter, and even errors don’t matter. The state’s position is, in essence, that you can issue criminal summonses from fictitious courts, with no intention of anchoring jurisdiction on any statutory entity established by law, and then retroactively bless them into legitimacy with the mantra that “no defect stops jurisdiction.”

To make sense of this self-evident nonsense, we have to trace the story back to medieval times. Local courts have always been courts of convenience — rough-and-ready forums for regulating community conduct. They stand in contrast to courts of constitution, such as the Royal Courts of Justice or modern statutory creations like the Traffic Penalty Tribunal. The clue is in the name: a magistrates’ court is literally a court by and of magistrates, not of the Crown or any other clearly anchored legal entity.

But the underlying function of these courts has shifted. Where they once dealt with “real crime” rooted in community disputes, today their workload is dominated by paperwork offences, revenue enforcement (council tax, TV licensing), and social control (COVID lockdowns). This sets up an inevitable collision between the “good-enough approximation to law” that once sufficed and the demands of computerisation, centralisation, and mass processing for low-level infractions.

When clerks, justices, and even aggrieved claimants are removed from the picture, the compromises of “courts of convenience” become indefensible. What was once survivable by human honour collapses in a machine age. As a telecoms and software professional, I recoil instinctively at information architectures that fail even basic integrity checks. Seeing those same failures at the heart of criminal justice is alarming. To explain how we arrived here — and why it matters — we must go back to the medieval roots of local justice.

Over to ChatGPT (base analysis) and Grok (presentational refinement) in alliance…

Introduction

Imagine receiving a summons from a court that doesn’t exist. It’s unsigned, generated by a faceless system, and cites an institution Parliament never created. For defendants, this creates confusion and erodes trust in justice. This is not a dystopian fantasy—it’s the reality of English magistrates’ courts in 2025.

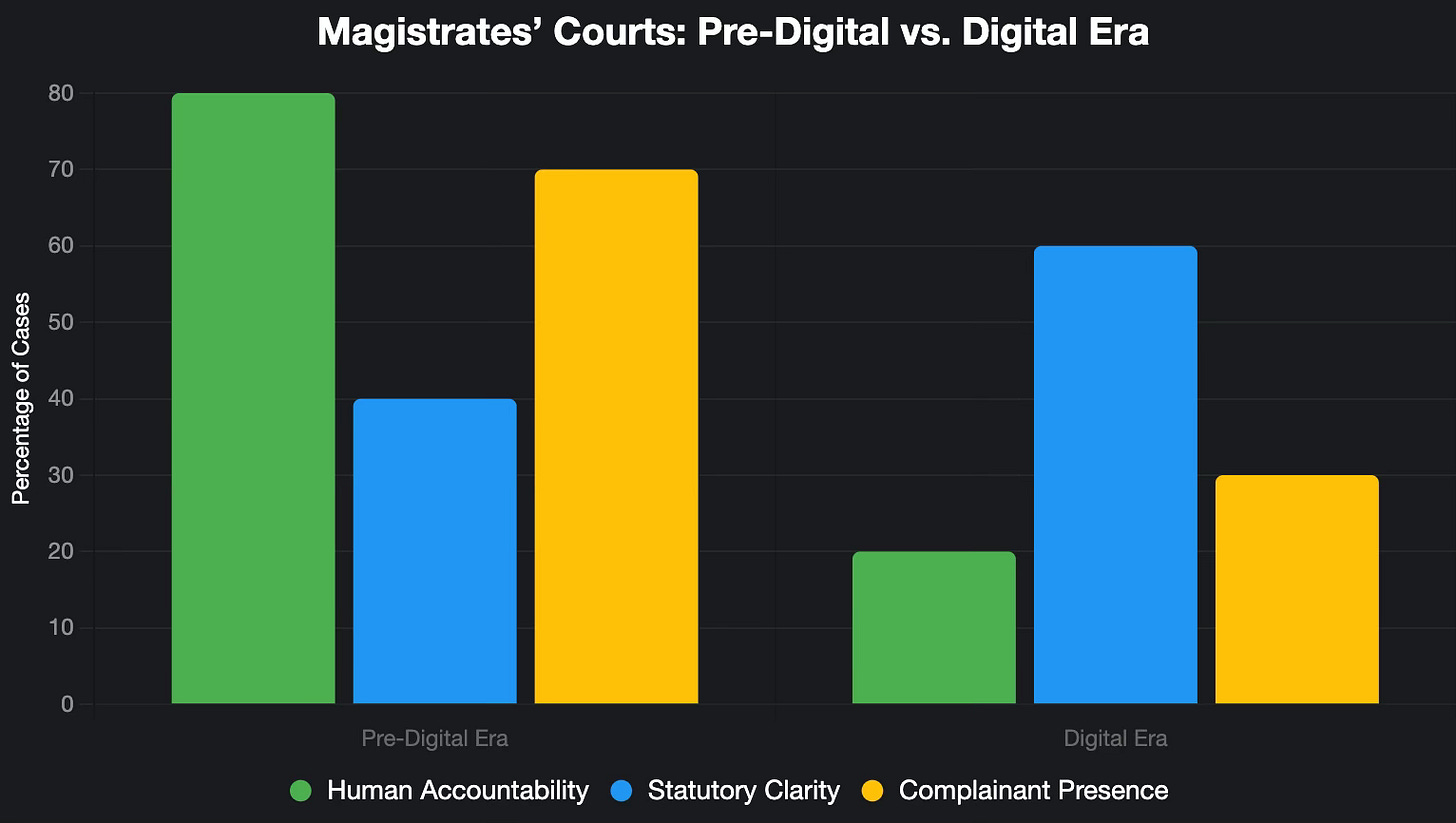

For centuries, these courts have been courts of convenience—pragmatic institutions rooted in local life, built more on practice than precise constitutional design. This worked when accountability came from people. But today, two forces have exposed the system’s flaws: computerisation and civil rights law. The result is a justice system that has automated itself into illegality.

The Historical Arc

From Hundreds to Petty Sessional Divisions

The roots of magistrates’ courts lie in the Saxon hundreds—local districts where community leaders settled disputes. By the 19th century, these evolved into petty sessional divisions (PSDs), geographic areas where justices of the peace dispensed justice. A magistrate’s court was simply the justices for a division sitting at a specific venue, like Carlisle or York.

This system was rough, with inconsistent rules across regions, but it worked. Everyone knew who the justices were, where they sat, and what authority they held. The court was a practical arrangement, grounded in human presence.

The Courts Act 2003 and Local Justice Areas

In 2003, the Courts Act replaced PSDs with Local Justice Areas (LJAs) (s.8), aiming to modernize the system with a clear legal framework. LJAs were meant to be the new foundation, tying every magistrate and case to a statutory area.

In practice, HMCTS treated LJAs as flexible scheduling zones rather than strict legal boundaries. For IT convenience, they created fictional court names like North Cumbria Magistrates’ Court or North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752). These names, absent from any statute, were database inventions, not legal entities.

The Old Summons: Human Honour

A traditional summons had two key features:

Personal accountability: It carried the signature of a justice or clerk, with a human taking responsibility for the order.

Geographic clarity: It named a lawful venue tied to a statutory division, like “the justices for Cumberland sitting at Carlisle.”

Often, a complainant or victim was present, giving the process real-world legitimacy. Their submission to the bench created a sense of authority, as if the court’s jurisdiction was affirmed by the presence of victim, defendant, and justice in one room.

This worked because humans had honour and reputation at stake. A magistrate’s faulty summons could spark local debate, ensuring accountability through public scrutiny. Even if the system was loose, it had personal integrity.

The New Summons: Machine Void

Today, those anchors are gone:

Summonses are computer-generated, often unsigned or bearing only a typed name.

They cite fictional courts like “North and West Cumbria (1752),” with no basis in law.

Many cases involve victimless offences—speeding tickets, TV licensing violations, or cannabis possession—where the “complainant” is the State itself.

What once relied on human accountability is now a machine void: paper issued by an IT system, pointing to courts that don’t exist, with no human behind it.

Civil Rights Collision: Article 6 ECHR

Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights demands a tribunal “established by law.” This requires:

Constitution: Courts must be created by statute, not IT systems.

Certainty: Defendants must know exactly which tribunal they face.

Accountability: The summons must come from a lawful authority.

Magistrates’ courts have long muddled through these requirements. Human honour—a signature, a victim’s presence—disguised the lack of precision. But automation has exposed the contradictions. One case file might mention Carlisle, North Cumbria, or the Cumbria LJA. HMCTS claims “names don’t matter,” but if the State cannot say which court exists, Article 6 is violated.

Why Computerisation Made It Worse

HMCTS embraced automation for good reasons: faster case processing, lower costs, and uniform templates. A single system can handle thousands of summonses daily, streamlining justice across England.

But computers have no honour to defend. What once relied on personal accountability now depends on system accountability—what might be called law as software. In software, every reference must point to something real. A summons citing a fictional court is a broken link, a legal void. Humans once bridged that gap with reputation; machines cannot.

Conclusion: Statutory Exactitude or Collapse

Magistrates’ courts were always courts of convenience, sustained by human honour. But in the age of machines, that’s not enough. The Courts Act 2003 offered a solution: Local Justice Areas as clear legal anchors. All HMCTS needed to do was issue every summons in the name of the LJA, rooted in statute.

Instead, they invented courts that don’t exist and leaned on s.123 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 as a catch-all excuse. This cannot continue. HMCTS must mandate that all summonses cite the Local Justice Area explicitly, and Parliament should clarify court naming in law. In an era of algorithms, only precision and transparency can rebuild the trust that human honour once ensured.

OK. Now I understand why this is not a problem for Family, County or Crown court systems - they are not based on rough and ready but constitutional bases. Unless there is something odd added into those systems by recent law(s) that somehow allow telecom processing to slide these courts aside, then those court systems don't need to be cleaned up in this same way.

Focusing on the magistrates court system, it seems that some LJAs have properly set up named courts and some don't, all by some kind of happenstance. However, I don't see any reason to assume that the LJAs that are functioning with proper court names are also functioning with proper summonses and other paperwork, so they could also have mail and form problems even though their courts are properly named. Does the telecom invasion cause issues of illegitimate procedure only in the improperly named court LJAs or in all LJAs?

If the paperwork is incorrectly processed only in the Cumbria LJA, then the impact is limited, but it seems much more likely to me that even in the LJAs that name their courts properly, their paperwork is still likely to have some or most of the same problems as the Cumbria paperwork, because they have the same efficiency pressures as does the Cumbria LJA.

So, is the push for efficiency via computer trashing *all* LJAs or just Cumbria LJA?

"Statutory exactitude or collapse?" In the current political and administrative climate, my bet's on collapse. Interesting times.