Genuine or fraud? A taxonomy of court naming schemes

By describing the "shades of grey" in legitimate court names, the "red line" of fraud is defined — and HMCTS has crossed it with "ghost courts"

Would the rolling back of millions of low-level convictions, because the State committed fraud on the summons, be the biggest scandal in British legal history? I don’t relish the thought, but as a victim of a “ghost court” myself, I have felt the harm and prejudice that this misrepresentation of authority imposes. If HMCTS practice were truly legitimate, they would not need to brush off challenges as “pseudo-legal” while at the same time reaching for obscure case law to justify it. A real court would tell you what the name at the top of the summons means. When instead you are mocked for asking, that is the tell.

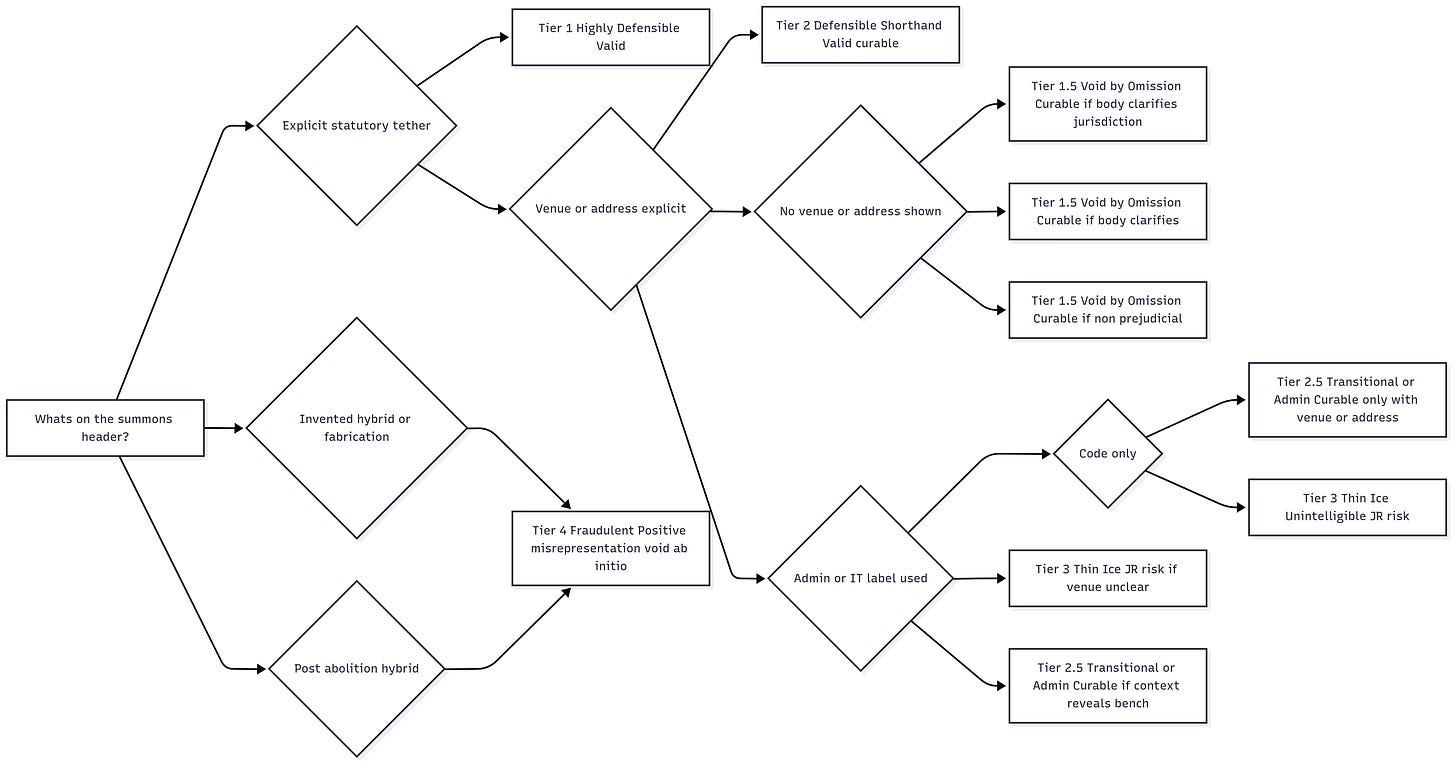

I spent my Sunday producing a 20-page white paper on court naming. To my knowledge, it is the first attempt to map out the full taxonomy of naming schemes used in magistrates’ courts — from the constitutionally defensible to the constitutionally void, even drifting into criminal territory. The header image is a schematic of that framework, with the detailed paper presented below. Think of it as an “executable essay”: feed it into your own AI engine and you can generate a tailored jurisdictional challenge for your own circumstances.

The key point is this: AI has broken the monopoly of the legal profession on constitutional analysis. You and I now likely have a clearer map of this terrain than the Ministry of Justice or the Government Legal Department did until now (and I suspect they are quietly watching — hi!). Anything that is not aligned with Logos is ripped apart by AI in seconds; contradictions and incoherences surface instantly. Systemic or architectural fraud cannot hide behind normalisation. Constitutional audit is now in the hands of every civilian willing to apply effort.

Here is an extract from the upcoming paper, with the core insight into the tiers of defensibility of court naming practises. Enjoy!

Tier 1: Highly Defensible (explicitly unassailable)

The following naming conventions are effectively bulletproof, as they point directly to the statutory base without need for interpretation or administrative gloss:

“The Magistrates’ Court for [Local Justice Area]”

— direct statutory tether under Courts Act 2003 s.10.“The Justices of the Peace for [LJA] sitting under the Courts Act 2003”

— emphasises the bench as the court, historically used in warrants.“The Magistrates’ Court constituted under the Courts Act 2003 for [LJA]”

— explicit statutory basis.“The Magistrates’ Court for the Commission Area of England and Wales”

— post-2003 national form, defensible for unified jurisdiction cases.

Tier 1.5: Void by omission (curable if non-prejudicial)

This tier covers cases where a summons satisfies the core statutory requirements — it is issued under lawful authority, specifies the alleged offence, and is served correctly — but fails to name the juridical court. The omission severs the direct link to the statutory base, creating a defect in form. If promptly clarified and no prejudice is caused to the defendant (for example, where the correct court can be readily identified from context or supporting documents), the defect may be curable. If not, the omission risks escalating into a jurisdictional nullity.

Typical examples include:

Blank heading with only venue in body (e.g., “Summons to appear at Carlisle Magistrates’ Court”).

Estate/Generic only (e.g., “North Cumbria Court House, Rickergate”).

“Magistrates’ Court sitting at [Venue]” with no header – omission variant, valid if clarified elsewhere.

While such forms fail CrimPR 7.4 identification, and are technically void, they are not fraudulent: omission is not misrepresentation. Equity may cure the defect if jurisdiction can be clarified from context (e.g. prosecutor or offence details) under MCA 1980 s.123 and CPR r.3.10.

Tier 2: Defensible shorthand (valid, curable by context)

This tier captures naming conventions that do not exactly mirror the statutory form but operate as widely understood shorthand. The summons can still be tied back to a lawfully constituted court, and defects are curable by context — for example, where the combination of LJA, venue, and prosecuting authority makes the tribunal’s identity clear.

Examples include:

“[Town/Venue] Magistrates’ Court”

— e.g., “Carlisle Magistrates’ Court,” historically standard shorthand for bench.“Magistrates’ Court sitting at [Venue]” with a header

— functional, historically common.“The Magistrates’ Court (as constituted under the Courts Act 2003)”

— generic statutory reference, valid if paired with address.

Tier 2.5: Transitional/administrative labels (marginally defensible)

This tier covers instances where a summons or order uses a label created for administrative convenience during periods of court consolidation or reorganisation. Such names may echo historic benches or estates (e.g. “North & East Cumbria Magistrates’ Court”) but lack a clear statutory root. They are not deliberate misrepresentations, yet they sit uneasily with CrimPR 7.4 because they obscure the juridical base.

These labels can sometimes be defended where context makes the intended tribunal obvious and no prejudice is caused — for example, if the correct LJA or venue is identified elsewhere in the documentation. However, reliance on transitional or invented administrative constructs erodes transparency and risks drifting into jurisdictional uncertainty.

Examples include:

“HMCTS Magistrates’ Court”

— reflects issuing agency (Courts Act 2003 s.2). Not a court name, but curable if context shows bench identity.“[LJA] Local Justice Area Magistrates’ Court”

— e.g., “North & West Cumbria Local Justice Area Magistrates’ Court.” Administrative, verbose, but tethered to statute.“[Code Only] (e.g., 1752)”

— lawful IT shorthand (CJS Data Standards), but curable only with venue and/or address for CrimPR 7.4 compliance.

Tier 3: Thin ice (confusing hybrids)

This tier covers hybrid naming constructs that mix statutory elements with administrative inventions, creating labels that look plausible but lack a clear juridical root. They are confusing because they gesture toward legitimacy while obscuring whether the tribunal exists in law. For instance:

[LJA Code + Venue] (e.g. “1752 Carlisle MC”)

— lawful if venue ties to reality, but risks judicial review if venue unclear.[Region + Venue] Magistrates’ Court (e.g. “North Cumbria Magistrates’ Court, Carlisle”)

— fuses a non-statutory regional label with a statutory venue, giving a false impression of legislative authority.[LJA + Courthouse Estate] (e.g. “West Cumbria LJA Court House”)

— blends a statutory LJA with an estate descriptor, but fails to identify the juridical court.“Magistrates’ Court sitting at [Venue], [Region]” (e.g. “Magistrates’ Court sitting at Carlisle, North Cumbria”)

— looks orthodox but introduces a regional overlay not found in statute.Code-only plus descriptor (e.g. “Court 1752 – Magistrates”)

— uses IT shorthand recognised in CJS data systems, but presented as a “court name” in its own right, falling foul of CrimPR 7.4.

Hybrids are still intelligible enough that HMCTS may claim “surplusage” if clarified elsewhere, but vulnerable to JR or appeal where prejudice is shown. Such hybrids undermine legitimacy, blur accountability, and create confusion across the process chain.

Tier 4: Borderline fraudulent (positive misrepresentation – void ab initio)

This tier marks the point where defective naming crosses from omission or ambiguity into prospective fraud. The label purports statutory authority where none exists, fabricating a tribunal rather than identifying one. Such misrepresentations cannot be cured under MCA 1980 s.123 or CPR r.3.10: they vitiate proceedings entirely, consistent with the principle in Anisminic [1969] 2 AC 147 that jurisdictional nullities cannot be insulated from review.

“[Hybrid Name + Code]” (e.g., “North & West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)”)

— fabricates entity, adds false specificity.“[Non-Court Body] Magistrates’ Court” (e.g., “[Council Name] Magistrates’ Court”)

— ultra vires, misleading issuer.Arbitrary inventions (e.g., “Narnia Magistrates’ Court”).

“Cumbria Magistrates’ Court” (if LJAs abolished post-Autumn 2025)

— post-abolition hybrid misrepresenting statutory structure.

Key distinctions

Valid (Tier 1/2): Statutory tether or accepted shorthand.

Marginally valid (Tier 2.5/3): Challengeable if unintelligible.

Void (Tier 1.5): Omission; curable to Tier 1/2 if no prejudice.

Borderline fraudulent (Tier 4): Affirmative misrepresentation of statutory authority.

While criminal fraud requires intent for prosecution under Fraud Act 2006 s.2, any fabrication is void ab initio for civil jurisdictional purposes.

Practical consequences

Quo warranto? No warrant, no jurisdiction!

The bottom line is: any invitation to show a warrant must show a warrant; if none can be shown, no jurisdiction arises.

Tier 1 (Highly Defensible): The warrant is evident on the face of the document — explicit statutory tether or lawful shorthand. Challenge unlikely to succeed (JR or appeal); treated as valid unless a separate procedural breach (e.g. no address).

Tier 1.5 (Void by Omission): The warrant can be inferred from the body (venue details, prosecutor, offence) but not the heading. Challenge possible via JR for failure to identify the court (CrimPR 7.4). Curable in equity if the underlying tribunal is clear. No fraud angle unless bad faith is proven.

Tier 2 (Defensible Shorthand): The warrant is recoverable from established statutory shorthand (e.g. venue name alone). Challengeable via case stated or JR if ambiguous, but curable under MCA s.123. Surplusage precedent (Argos [2022]) favours HMCTS.

Tier 2.5 (Administrative Labels): The warrant is obscured by HMCTS branding or codes, but traceable with effort. JR viable if confusion causes prejudice; equity may adjust. Not fraudulent unless dishonesty is shown.

Tier 3 (Thin Ice Hybrids): The warrant cannot be found on the face of the document (e.g. code-only, hybrid constructs). Likely JR success for unintelligibility under CrimPR 7.4. Fraud complaint arguable if deliberate obfuscation is proven.

Tier 4 (Borderline Fraudulent): The warrant is absent altogether — the entity named has no statutory existence. JR or appeal voids ab initio (Anisminic analogy). A criminal complaint is possible if intentional deception is evidenced. <<< YOU ARE HERE

This is content HMCTS never wanted published. I am sure you will, err, share it widely as a result!

😎

Standing back, the biggest takeaway from all of this is that the legal battlefield has been handed a new WMD and you are absolutely correct to point out that everybody can now obtain the depth of analysis that was previously reserved to chess champions.

A.I. Is here

NCSWIC

“Narnia Magistrates’ Court” - Delicious. :-D