Ministry of Justice proposes to abolish habeas corpus (unless we stop them)

A radical and unconstitutional guidance note for court legal advisors sneaks in removal of the foundational guarantee of liberty in English justice

I have been passed an extraordinary confession from the administrative state that carries explosive legal and political consequences. It is an internal guidance note for legal advisers in the magistrates’ courts. There used to be an independent Justice Clerks’ Society, but that has now been absorbed directly into the Ministry of Justice as the Justices’ Legal Advisers’ and Court Officers’ Service — the authors of this document. This entity has no public website, but the note is not confidential or secret: anyone could obtain a copy under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. As a minor public service, I have uploaded a copy to my own website — link here.

I strongly suspect this paper is a direct response to the challenges that I and a small group of others have been mounting to “ghost courts”: labels of “courts” on summonses and in IT systems that do not map to any statutory instrument or constituting warrant. The timing is revealing — dated August 2025. Such documents take months of drafting, review, and approval. That timing aligns with my own litigation history. If it is indeed a response to our collective pushback, then this is a major win. The state has been forced to say aloud what was previously unspeakable. A casual reader might miss it, but what lies within is a constitutional earthquake.

The title is prosaic enough: “Challenges to legality based on court names, LJA [Local Justice Area] titles, and alleged errors in process in magistrates’ courts.” But the content is remarkable. It is half political polemic, half legal analysis. The polemic is obvious: its tone drips with derision, its content cherry-picks supportive law, its purpose is damage control, and its effect is to delegitimise scrutiny. It constantly uses terms such as “pseudo-law,” “invented technicalities,” and “frivolous challenges.” That is political rhetoric, not neutral guidance. It is advocacy disguised as instruction.

The legal analysis is even more radical. The note pretends to be conservative but is in fact revolutionary. It downgrades a “court” from a verifiable truth-claim to a disposable label. According to this model, a “court” is either irrelevant text or a typo that can be reinterpreted away. This abandons the centuries-old requirement of a tribunal established by law. Instead, the document asserts that power flows simply from magistrates by virtue of their commission. That is the logic of the Star Chamber restored.

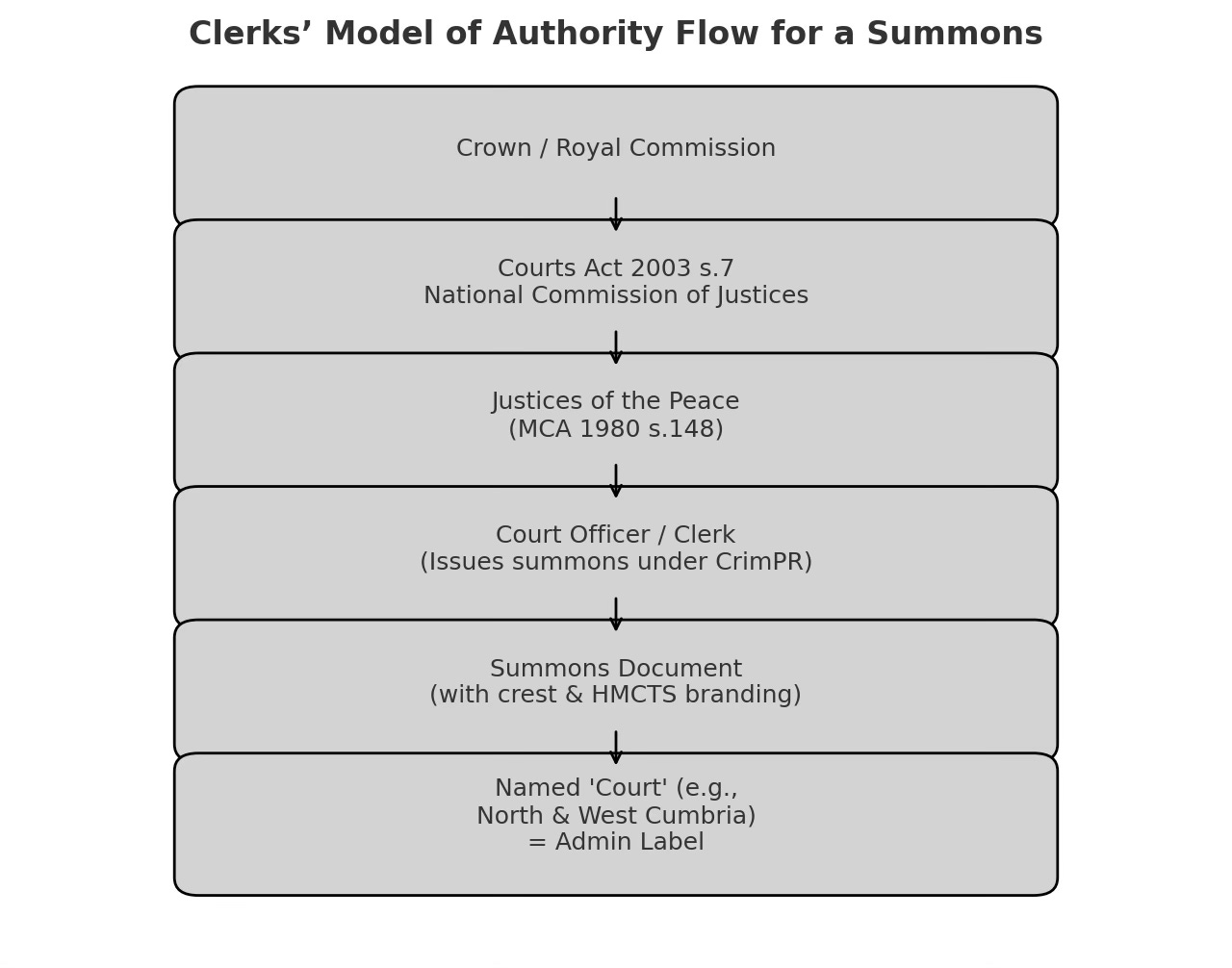

This is the model they imply, where authority flows through the administrators without any counter-balance of a tribunal established in law:

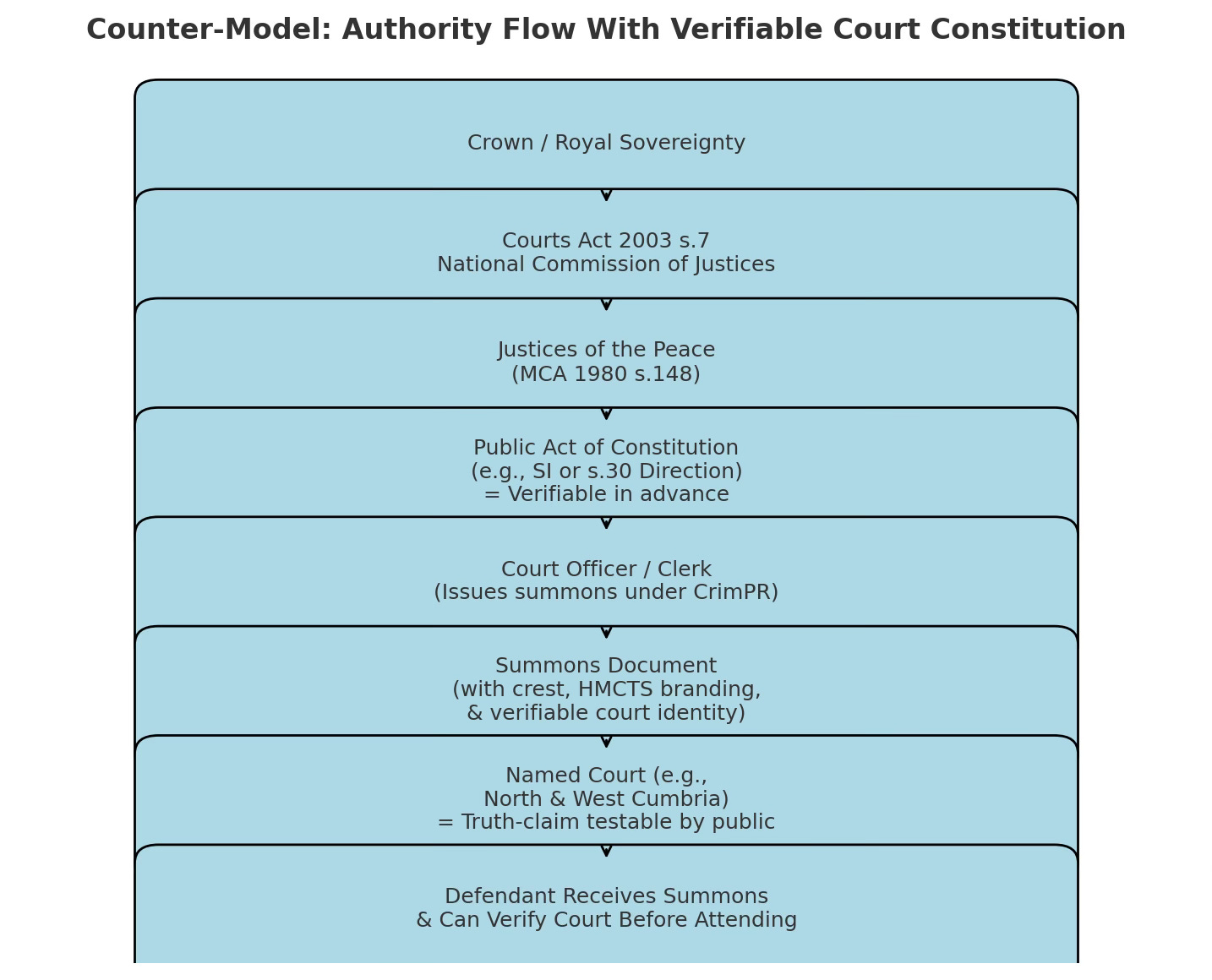

This is what is supposed to happen with a named court so the public can validate the authority claim of any coercive document or instrument:

Why is this switcheroo so serious? Because a court is not just a word — it is a public ledger of judicial events. The name of the court must be unambiguous, to prevent abuses like shadow courts or off-books punishments. What the Ministry of Justice is effectively normalising is taking all prosecutions off the books. You can be convicted and stripped of liberty without an explicitly named juridical entity behind the order. That reverses centuries of English law, reaching back before Magna Carta, when the people first insisted that authority be traceable and accountable. It is radical in the most dangerous sense of the word.

The tell comes at the enforcement stage. You can be fined or jailed based on an “order” that names only an IT label or administrative fiction. (Notably, in my own case, HMCTS refuses to give me an actual order for my supposed “conviction.”) The last protection against tyranny in English law is habeas corpus: “show me the body and the warrant.” But if the state no longer needs to name the court with traceable juridical ancestry, then habeas collapses. The clerks have manoeuvred themselves into an indefensible position: their sophistry abolishes the Great Writ.

The document’s claim that a court name is mere “surplusage” is staggering. They are not even arguing that the tribunal exists under some obscure statute. They are saying that it does not matter whether the named tribunal exists at all. That transforms the summons into an instrument of compulsion without any verifiable authority. And that, plainly put, is the abolition of the constitutional order of England.

Under their model, a tribunal springs into being whenever a case officer types a label into a computer. Jurisdiction no longer comes from Parliament but from bureaucratic usage. That is constitutional overreach of the highest order: the power to create courts by clerks and software. It is compounded by inequality: the defendant must state his identity truthfully, under penalty of perjury, while the state may respond with a name that is shifting, ambiguous, or untraceable.

This is why the memorandum is not a restatement of orthodoxy but an extreme doctrine of administrative supremacy. It hollows out habeas corpus, abandons equality of arms, and reduces law to whatever the executive says it is. That is indistinguishable from raw prerogative power — the very thing English constitutional development was designed to abolish.

It is the state, not the challenger, that peddles pseudo-law: conjuring tribunals from IT labels, delegitimising scrutiny with polemic, and redefining law as administrative habit. The accusation points backwards. What they call pseudo-law is, in truth, the defence of law; what they promote as law is the most dangerous pseudo-law of all.

The stakes are maximal — if we allow this, there is no lawful constraint on power.

Tacit abolition of habeas corpus must be resisted and stopped.

For the record, here is the AI analysis I did — you can perform your own.

The Overreach of the Clerks’ Argument

The August 2025 clerks’ memorandum purports to be practical guidance on “pseudo-legal” challenges. In truth it advances a radical constitutional claim. Its errors are twofold: first, in what it positively asserts; and second, in what it conspicuously refuses to confront.

1. What the Document Says — and Why It Is Wrong

(a) Court names are “surplusage.”

The memorandum asserts that the name of the court on a summons or warrant has no legal significance, that jurisdiction lies in “the justices” in the abstract, and that any label will do.

This is wrong. The Criminal Procedure Rules 2020 (Statutory Instrument 2020/759), Rule 7.4(c)(i), requires the summons to identify the court that issued it. That is not decoration but binding law. Its purpose is to allow a defendant to test the tribunal’s authority before compulsion. To call it “surplusage” is to contradict Parliament’s command.

(b) Section 123 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 cures all defects.

The memorandum treats section 123 (“no objection shall be allowed…for any defect in substance or form”) as a magic solvent.

But section 123 presupposes a valid tribunal. It can heal irregularities in a lawful summons; it cannot conjure a court from nothing. To treat a curative clause as a constitutive one is a category error.

(c) National commissioning makes identity irrelevant.

The memorandum leans on section 7 of the Courts Act 2003 (national commission of justices) as if it removed the need for tribunal identity altogether.

This collapses two distinct ideas: (1) justices may sit nationally; (2) therefore any administrative label suffices. The first is true; the second is false. Deployment does not abolish the need to know what tribunal sits.

(d) Challenges are “pseudo-legal.”

The memo calls all objections “pseudo-law,” thereby assuming the conclusion it is meant to prove. This rhetoric displaces argument: it sidesteps statutory requirements (like CrimPR 7.4) by labelling them frivolous rather than answering them.

2. What the Document Does Not Say — and Why It Matters

(a) Silence on habeas corpus.

The Great Writ is never mentioned. Yet habeas corpus exists precisely to test whether a detention flows from a lawful court. If court identity is “surplusage,” then the prisoner cannot demand “By what court am I held?” That omission is not minor; it is fatal.

(b) Silence on Article 6 ECHR and Article 14 ICCPR.

The memo ignores the state’s binding duty to guarantee a tribunal “established by law.” This is not peripheral: it is applied daily in UK courts via the Human Rights Act 1998. To omit it is selective and misleading.

(c) Silence on statutory basis for names.

No statutory or administrative act (such as a direction under section 30 of the Courts Act 2003) is identified to ground names like “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court.” Instead, the memo leans on IT codes and usage — precisely the gap critics highlight.

(d) Silence on reciprocity.

The defendant must declare identity truthfully on pain of perjury. Yet the state offers an ambiguous, shifting, or untraceable tribunal name, with no acknowledgement of the asymmetry. That collapses “equality of arms,” a core requirement of Article 6.

3. Why These Errors and Omissions Are Polemical

What the memorandum asserts is wrong (e.g. surplusage, section 123 as a panacea). What it omits is fatal (habeas corpus, Article 6, constituting instrument). The combination shows its true character: not neutral guidance but partisan polemic designed to deter scrutiny.

The overreach lies here: by redefining “court” to be irrelevant, contingent, or opaque, the clerks claim to defend orthodoxy while advancing a radical proposition — that the public has no right to verify the authority of the tribunal that seeks to punish them.

Conclusion: Habeas Corpus as the Final Test

At the end of the line, the memorandum’s theory cannot survive habeas corpus. The writ demands a lawful warrant from a lawfully constituted court. If court identity is dismissed as irrelevant, then habeas is stripped of content — a prisoner could not demand “By what lawful court am I held?” That is the very definition of constitutional collapse.

The choice is binary: either “court” remains a verifiable truth-claim, and habeas corpus still lives; or it is not, and habeas corpus is pseudo-law. The clerks have chosen the latter without admitting it. It is for the High Court, and ultimately Parliament and the people, to decide whether to tolerate such an extreme and radical departure from centuries of English law.

So interesting to see the writer has avoided naming Martin to avoid what happened to the last ‘useful idiot’ Joann Middleton the ‘Editor’ of the government funded JCS Matters who disseminated similarly biased prejudicial ‘advice’ to the judiciary during live cases designed to sway the outcome and in effect pervert the course of justice. What you are seeing here is the M.O. displayed for all to see and the inner workings of how ‘our’ government rinses its citizens through its pseudo-Courts.

At some point the guard will slip entirely and everyone will recognise the Government Revenue Courts ( previously called Magistrates’ courts ) as exactly that. Either the MOJ need to convene the courts on a lawful basis or suffer the pushback that this ‘guidance note’ attempts to resist. The impartiality of legal advisors is nowhere to be seen as they have degenerated into a 5th column shill army and they need to shape up or ship out…

At last, things are getting deliciously interesting. What a find. But I am still interested in finding out whether the original legislation on which these three layers of courts were reconstituted into national courts sitting at various locations were tightly written such that the bureaucrats are exceeding their authority or whether the legislation was designed to allow/encourage bureaucrats to slide around the constitution and precedent to enable wealth extraction via confusion and obfuscation. Where does the malfeasance begin? Where is its root?