My "slave man of the sea" weekend retreat

A trip report from a private gathering in southern England of freedom activists

I have just enjoyed a short break from my laptop at a camping weekend with colleagues on similar journeys — challenging the lawfulness of state bodies, and exploring how parallel systems might be built on foundations closer to natural justice. Not everyone agrees on what a better world should look like, only that the one we have is unsatisfactory, unfair, and in many places openly criminal. The themes promoted are often smeared under the “freeman of the land” or “sovereign citizen” labels, but that caricature hides the complexity and nuance of this space.

There is a whole spectrum of responses to tyranny — from the well-meaning but naïve, through to the dutifully proper and constitutional. Being outside the current orthodoxy does not make something false, but neither is it true simply because it challenges what is broken. It may indeed be that we have been turned into surety for birth-certificate bonds and denied our status as children of God. Yet at the same time, “your” property can still be seized for unpaid Council Tax, since ownership is ultimately a Crown loan with use-rights only. If you choose to live inside their debt-money system, you play by their rules.

My own path is paradoxical. Where others seek to exit the system, I have gone in the opposite direction — fully embracing my “slave man of the sea” status under maritime law. I make no special claim to sovereign status; I simply give voice to my legal name and use my role as “defendant” to stand within their framework. I do not resist, defy, or obstruct. Rather than trying to collapse the Single Justice Procedure or magistrates’ courts, I merely show that, on their own terms, they have already collapsed — because they rely on non-statutory names on their own legal instruments.

With that framing in mind, let me take you on a tour of some of the talks and themes I heard over the weekend.

As with many such gatherings, several talks circled familiar ground. How administrative edict has displaced constitutional law. How in personam (legal fictions) have been substituted for in rem (real things) to abstract away rights. How the metaphor of vessels and cargos is applied to men and women. How language is twisted so that we trick ourselves into surrendering what is already ours. The Bar guild as gatekeepers. Jurisdiction fraud, name fraud, trust fraud, and high treason. Status correction, usurpation, usury, usufruct. Corporatisation, securitisation. Affidavits, notices, juries, arms, fiduciaries, crowns, commoners.

Others are better placed to evaluate these claims. Someday I may attempt a write-up of “freeman of the land” assertions and score them on a “truth-to-trope” scale. Almost always there is a thread of truth somewhere in the weave, but law is messy — it always has been. I do not see salvation in grammar, paperwork, or dictionaries. What came through again and again is that we are dealing with a spiritual malaise, but defining that is harder than issuing notices or drafting trusts. Much of the sovereignty movement operates in self-will, and so inevitably reconstructs the same systems of rules and adjudication as those it claims to oppose. The cycle repeats.

There were specific legislative references I wrote down, with (skeptical) AI-aided explanations:

English Civil War Statutes (1640s) — Parliament passed laws such as the Triennial Act 1641, reducing royal prerogative and strengthening habeas corpus. Historians see this as the beginning of parliamentary supremacy and the end of absolute monarchy. Sovereign claim: proof that the people can lawfully resist and overthrow unlawful government.

Act of Settlement (1701/02) — The Act secured Protestant succession and restricted the monarch’s power. It is generally regarded as a cornerstone of constitutional monarchy. Sovereign claim: it nullified all earlier statutes, creating a jurisdictional reset.

Acts of Union (1707) — United the parliaments of England and Scotland into Great Britain. Generally accepted as the legal foundation of the United Kingdom. Sovereign claim: voided the “Bar guild,” triggered riots, and delegitimised the courts.

British Nationality Act (1948, s.17) — Allowed certain Commonwealth and Colonial subjects to register as Citizens of the UK and Colonies. Seen as post-war nationality reform. Sovereign claim: converted Englishmen into “British persons,” reducing them to corporate entities.

Births and Deaths Registration Act (1953, s.17) — Consolidated prior laws on birth/death records and allowed corrections. Seen as administrative record-keeping. Sovereign claim: registering a name creates a state-owned legal fiction.

State Immunity Act (1978) — Codified the principle that foreign states are generally immune from suit in UK courts. Recognised internationally as a diplomatic law instrument. Sovereign claim: proves the UK state and its officers enjoy blanket immunity from accountability.

British Nationality Act (1981) — Replaced CUKC status with new categories like British Citizen and British Overseas Citizen. Generally seen as a decolonisation-era update. Sovereign claim: reclassified all English people as “British persons,” stripping natural rights.

“British Corporation” (1967) — No Act of Parliament exists; the reference stems from corporate or IMF records misreadings. Generally accepted as myth or confusion. Sovereign claim: 1967 marked the state’s conversion into a private corporation trading citizens as assets.

Civil Contingencies Act (2004) — Grants ministers temporary powers in emergencies to override statutes. Seen as a framework for disaster response with safeguards. Sovereign claim: Parliament gave itself dictatorial powers to suspend common law at will.

“Kilmore letter” to Edward Heath (1960) — Said in sovereign circles to prove Parliament/police are corporate bodies. No historical record confirms its existence. Sovereign claim: evidence of post-war treason and corporate takeover of governance.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (signed 1982, ratified 1997) — Defines maritime zones, navigation rights, and resource jurisdiction. Seen as an international treaty on ocean law. Sovereign claim: imported admiralty law into domestic courts, converting people into vessels/chattel.

Companies Act (2006, s.790) — Modernised UK company law and required registers of “persons with significant control.” Accepted as a corporate transparency reform. Sovereign claim: proves all persons are treated as corporations and individuals as sureties.

European Union (Withdrawal) Act (2018) — Repealed the European Communities Act 1972 and preserved retained EU law. Generally seen as Parliament reclaiming sovereignty while ensuring continuity. Sovereign claim: Parliament and EU law placed above common law, erasing ancient rights.

Data Protection Act (2018, s.170) — Created an offence for unlawfully obtaining or disclosing personal data. Seen as an implementation of GDPR standards. Sovereign claim: government officers and courts are personally liable for any request of personal data.

All I know for sure is that the procedures for things like Council Tax collection offend ordinary conscience and due process. My own sense of the sovereign claims is that they are often “mostly true, but unhelpful.” They point to something real — systemic fraud, jurisdictional sleight-of-hand, exploitation — yet they do not by themselves provide a remedy. What is missing is a wider cosmology, one that accounts for multi-generational infiltration, covert wars, and the primacy of military power over civilian law. No land is truly “owned” unless it can be defended; feudal structures return again and again because armies must be funded, and the people always pay.

This suggests that neither the mockers of the sovereignty movement, nor the “rebels with a statement of fees,” hold the full picture. The deeper treason, and the invisible tussles of power behind it, are likely known only to a very few. What we see on the surface is always partial, while what is hidden in plain sight often shapes events far more than official history admits. The legal system can be both corrupt and, at the same time, a mirror of the people’s own selfishness. After the lockdowns and medical coercion of the Covid era, it is natural that many now question the legitimacy of the whole edifice.

A few things did get my attention:

That the legal system is not Satanic (i.e. inverted), but leveraged for Satanic uses.

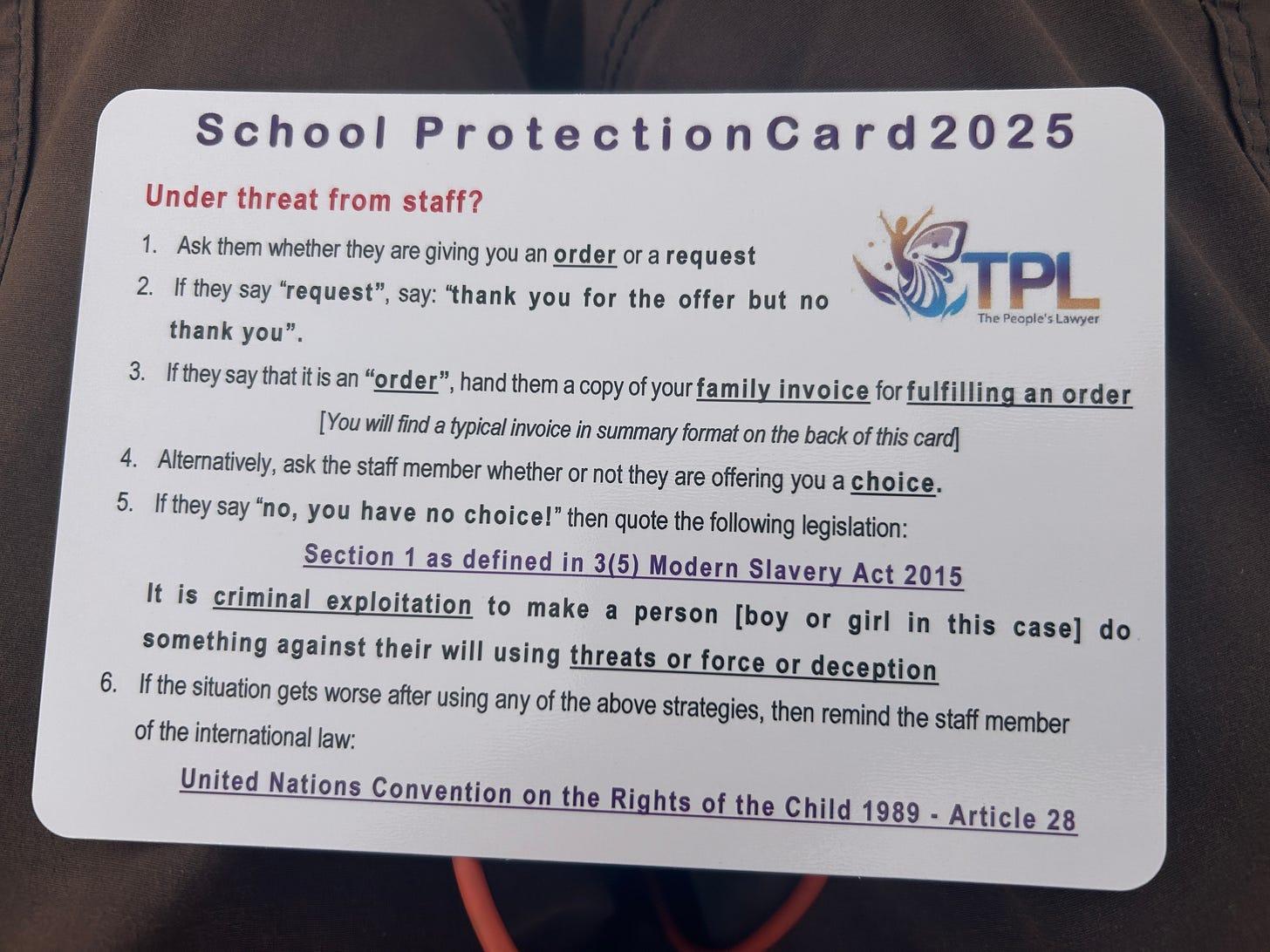

The coalface of WW3 is the classroom — and indoctrination of the young.

“All horses in a race go somewhere, even if not winning post” — so there is learning value in every challenge.

Many people are doing good things inside the existing structures in innovative ways: developing land, protecting debtors, and even learning traditional “defence of the realm” skills like archery. Much of the sovereign movement is “just people going about their private business without asking the state for permission first”. Nowt wrong with that!

As I fed my notes into AI, it seemed to articulate why the sovereignty movement, shorn of an anchor into military intelligence and theology, tends to struggle. You may or may not agree with this diagnosis, but it is a provocation that begins a conversation:

The sovereignty movement struggles first because of misunderstanding. Many of its adherents sense real corruption — trust fraud, language manipulation, the conversion of people into legal fictions — yet they lack the precision to separate genuine constitutional defects from folklore. As a result, truths are mixed with tropes, and valid grievances about jurisdiction or due process get lost in claims that rest on shaky readings of statutes, grammar, or etymology.

It also struggles because of the nature of the problem itself. The corruption is not a surface error that can be fixed with paperwork; it is multi-generational infiltration, covert financial warfare, and the primacy of military power hidden behind civilian courts. Sovereign remedies often try to confront symptoms with documents or declarations, but the underlying architecture — debt money, Crown ownership, feudal structures — is what drives the injustice. Without acknowledging that deeper cosmology, many of the solutions cannot work.

Finally, the movement struggles due to contradictions within itself. It condemns the state’s rule by edict, yet often reproduces mirror-image systems of rules, fees, and gatekeepers. It prizes independence, yet frequently collapses into self-will and fragmentation. It calls for higher law and divine order, yet remains bound up in paperwork, affidavits, and notice-serving — tools borrowed from the very system it opposes. These contradictions keep the cycle repeating, preventing the movement from cohering into the constitutional repair it longs for.

If nothing else, the sovereignty debates have already achieved something significant. They have made many people pause to question the language they use in public affairs, rethink their assumptions about the state’s power and remit, and challenge the state to prove its authority where it may be lacking. That alone is no small achievement.

In my own case, the fact that the Justices’ Clerks’ Society was compelled to publish its doctrine on court names is itself the “win,” even if it was delivered with rudeness. Once a doctrine is laid out, it cannot be hidden again. The ambiguity in court names and their legal meaning is no longer an obscure quibble — it is now a matter of ordinary political and legal debate, precisely where it belongs.

The people do, and must, have a seat at the table to ask whether our legal structures truly serve the public interest, and whether they feel legitimate. That is not obstruction; it is citizenship. And once such questions are asked openly, legitimacy has to be earned, not presumed.

It is often in the micro-behaviours that one glimpses the unconscious truth, and the sovereign space is no exception. There is plenty of “herding cats,” as the undisciplined energy of the movement continually rubs against the rigid proceduralism of state bureaucracy. The contrast itself is telling: both sides are caught in patterns, one of disorder and the other of over-order.

Perhaps the most noteworthy fruit of the weekend was not a new legal template or affidavit, but a professional-grade song — setting an existing poem about sovereignty and not being reduced to a number into music. Such cultural artefacts may shape the long run more than another notice of estoppel posted to a council office. Music speaks where paperwork falters.

Whatever happens with central banking or the architecture of debt slavery — whether those delinquent institutions stand or fall — the “sovereign show” goes on. It mutates, evolves, and continues to embody the restless search for legitimacy, dignity, and freedom.

The rule of law is intentionally being removed from the western world , this in part serves the Great Reset and the role out of the CBDC and the asset stripping of the proletariat.

How can you seek justice in a lawless state?

This best video I have so far seen on this is:

The Market Sniper (utube channel)

John Titus on the end of the rule of law.

I would urge all to watch🙏👍🤝

Another channel well worth watching is : Windows On The World 🏁

There could be an easy way to stop it:

we do a mass walkout and don't turn up at work and put our governmental on notice and give them the terms of our own reset.

As usual, a very worthy tome, Martin. What speaks volumes are our own failings. Spiritual enlightenment and personal humility are key to ending our slavery, but few humans will rise to the occasion, our egos always get in the way. We will get there, but it will take time. It will be hard on those whose Christ consciousness has set them on the good path because they will have to accommodate the ignorant. But, hasn’t it always been thus? At least, we know humanity is going in the right direction now. I am reminded and comforted by the words in “Desiderata”: “…no doubt the Earth is unfolding as it should.”