No "escape hatch" from jurisdiction fraud

Why using a "ghost court" name is an incurable defect, not administrative error

I hope readers will forgive me for banging on about one topic at the exclusion of all others, but I appear to be at the “tip of the spear” of the biggest scandal to hit the British judiciary in approximately forever. Mass automation of low-level convictions has resulted in the use of fake court names as the origin of authority to summons, prosecute, and punish. This is not a trivial matter: if we let this slip by, it means we are willing to accept any kind of legal theatre that simulates justice, while disallowing redress, as the initiating entity is not real and cannot be sued. That is the end of the rule of law as we know it, and cannot be permitted.

As a companion to yesterday’s reusable piece giving a full statutory breakdown of the “ghost court” issue, here is another AI-generated analysis of why a “ghost court” is not some administrative error that can be overlooked. If the court name was misspelled, that would not stop the court from existing and proceedings being lawful; a “fix” is legitimate. If it was a transitional period between different names, and the court name had been used beyond its official “use by” date, that could also be excused. But to invent a court out of nowhere, templated off some other administrative name with no juridical authority, is plain old fashioned fraud. A “ghost court” is a non-court, and always stays that way.

I have lightly edited and annotated this analysis for my international readership, as it is quite educational. The silver lining in this painful episode is that I am being taught constitutional law at a visceral level, not out of curiosity, but because I need to preserve my right to travel and stop debt collectors stealing my few possessions on a false premise. I won’t be surprised if, as with the Post Office Horizon IT scandal, that the Single Justice Procedure’s architectural corruption has resulted in many suicides, ruined families, and destitute victims. The automation of injustice, sustained through administrative violence, is horrific to endure — and I speak from my own experience.

Over to ChatGPT… with a final commentary by me afterwards.

Overview

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS), or any presiding judge cannot lawfully evade the consequences of initiating proceedings under the name "North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)", which is not a court established by law. Every attempted 'escape hatch'—whether based on venue flexibility, transitional administration, or digital efficiency—fails under scrutiny. This document synthesises the original brief with expanded legal reasoning and doctrinal reinforcements from Grok, including:

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Response dated 14 May 2025 (Ref: 250429009)

Courts Act 2003 [which is the legislation that lawfully “courtifies” any tribunal]

Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 (MCA) [which governs procedure in lower courts]

CrimPR 2020 [the criminal procedure rules]

Judicial Review and Courts Act 2022 (JRCA) [the interface to supervisory courts]

Key precedents: Anisminic, Privacy International, Hill, Sunderland, Benham, Soneji

1. Courts Act 2003 s.30 – Flexible Venue

Apparent Escape: A magistrates’ court can sit “at any place” [like “sitting at Carlisle Magistrates’ Court”] so “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court” is just a venue label.

Why It Fails:

s.30 presumes a court already constituted under Courts Act 2003 s.4(1) and Schedule 1.

Venue ≠ institution. Sitting in a community hall doesn’t create a “Community Court.”

FOIA response confirms no such court has been established by Statutory Instrument [i.e. secondary legislation that fills out operational details] —this label is purely administrative.

CrimPR r.7.2(3)(b) requires naming the court, not the place. [There are residential blocks with the name “Court” at the end, but holding a tribunal there doesn’t make it into a court of law.]

Precedent:

Sunderland City Council v PS [2018] EWHC 56 (Admin) – Misidentification voids proceedings, even if held in a valid location.

2. MCA 1980 s.121 – Place of Sitting

Apparent Escape: Justices can sit anywhere within the Local Justice Area; therefore, the court’s name is immaterial.

Why It Fails:

s.121 applies after a court is properly constituted under MCA s.150.

A court must exist before it may sit [and any operational rules kick in]. “Sitting as a court” ≠ “being a court.”

FOIA confirms the administrative label does not denote a valid court.

Precedent:

Anisminic Ltd v FCC [1969] 2 AC 147 – Jurisdictional error renders a decision null regardless of apparent compliance.

3. CrimPR r.3.10 – Rectifying Mistakes

Apparent Escape: Naming a ghost court is just an error—CrimPR r.3.10 permits correction.

Why It Fails:

Rule 3.10 allows a court to rectify its own mistakes. If there is no court, there is nothing to correct [so ontology precedes procedure].

A nullity is not a clerical error—it is an incurable jurisdictional defect.

Precedents:

Privacy International v Investigatory Powers Tribunal [2019] UKSC 22 – Jurisdictional voids are unrectifiable.

R v Soneji [2005] UKHL 49 – Statutory non-compliance voids unless otherwise expressly allowed.

4. Judicial Review and Courts Act 2022 s.1 – Suspended Quashing

Apparent Escape: In Judicial Review [by the High Court], a judge could suspend quashing to allow administrative correction.

Why It Fails:

JRCA s.1 applies only where an error occurred within a valid proceeding.

You cannot suspend the consequences of a void. There was no valid court, no valid process, and thus nothing to quash.

Precedents:

Anisminic and Privacy International – A legal nullity is not remediable through discretion.

JRCA s.1(9) requires “adequate redress” be possible—no such redress exists for ab initio voids.

5. Courts Act 2003 s.109 – Transitional Provisions

Apparent Escape: Legacy naming conventions may still be in effect [as courts are merged or moved].

Why It Fails:

s.109 preserves known courts, not fictional ones.

The 2015 LJA Order (SI 2015/1506) governs current court naming. “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)” is not listed in any such instrument.

FOIA confirms: No statutory authority, no establishment, no lawful court.

6. MCA 1980 s.2 – Jurisdiction by Area

Apparent Escape: Jurisdiction is conferred by Local Justice Area—if the case is within the area, it is valid.

Why It Fails:

Jurisdiction is exercised by a court, not an area.

MCA s.2 cannot substitute for CrimPR r.7.2(3)(b), which requires naming an actual court—not a catchment zone.

Analogy: A postcode doesn’t substitute for a passport. Location ≠ institution.

7. Administrative Labels / Automation (JRCA Sch.2, CJA 2003 Sch.3)

Apparent Escape: Digital systems may abbreviate or administratively simplify court names.

Why It Fails:

CrimPR r.7.2(3)(b): The Single Justice Procedure Notice [that comes before the summons] must name the court, not an informal label.

MCA s.1: Information must be laid before a real court—not a placeholder.

Automation must comply with constitutional law. Benham v UK [1996] 22 EHRR 293 – Art.6 requires a “tribunal established by law.”

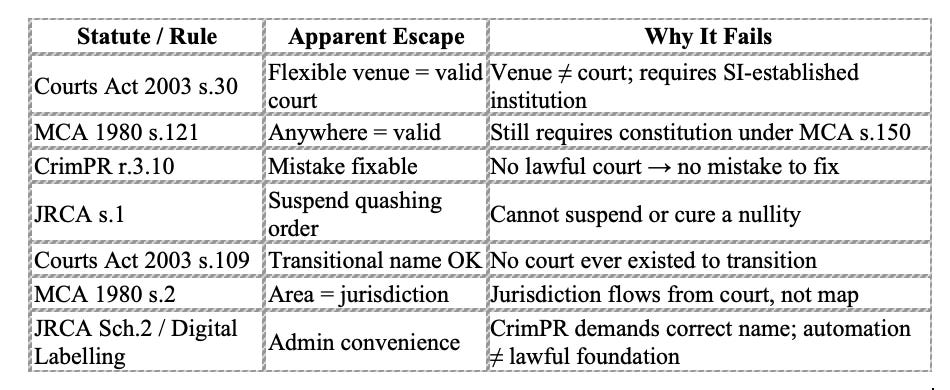

Summary Table

Final Conclusion

There is no escape.

Every proposed justification collapses under legal scrutiny. The failure is not procedural, but constitutional. No statutory provision cited can bypass the requirement that a magistrates’ court must be:

Established by law (Courts Act 2003 s.4 + SI),

Constituted under MCA 1980 s.150, and

Correctly named on the originating notice (CrimPR r.7.2(3)(b)).

The proceeding is a nullity ab initio. No CPS logic, HMCTS patch, or judicial workaround can repair it.

Back to Martin…

I know—intuitively and circumstantially—that HMCTS and CPS are reading these articles. They would be foolish not to. I am making one of the most serious and constitutionally grounded challenges to judicial authority in living memory. This is not some procedural quibble or disruptive tangent. It is common sense that a criminal conviction cannot arise from a misrepresented authority—neither legally, logically, nor morally. The nullity I describe is not something I invented; it pre-exists my exposure of it. The consequences—the voids—are not hypotheticals. They are “real non-realities”, and they are already harming lives.

This gross administrative failure is forgivable, but only if it is faced, acknowledged, and corrected. The solution requires courage, not cover-ups. Our society needs healing, not institutional self-mutilation. A system that respects the rule of law must demonstrate accountability when that law is broken—even by the system itself.

Civil servants and administrators deserve a “grace and mercy” exit ramp—a path that allows them to step away with dignity and honour intact. But if you continue to knowingly run void prosecutions, you forfeit that grace. You then deserve the same criminal penalties you so casually impose on others—often in breach of your own statutory duties. The hypocrisy is no longer hidden.

I am publishing this so that EVERYONE understands the stakes. This is not vexatious. It is not frivolous. It is the highest form of public service: to challenge the jurisdiction of a court that does not lawfully exist.

You are violating CrimPR. You are ignoring your duties under the Courts Act and the Magistrates’ Courts Act. You are abusing the Single Justice Procedure. And you are destroying lives—through administrative violence, constitutional evasion, and procedural collapse.

I can just about survive it. Others cannot. And that is why jurisdiction fraud is a serious crime.

It is also why misconduct in public office remains a common law offence carrying a sentence of life imprisonment.

Let that sink in. Let this be a turning point. And let justice be restored before justice becomes impossible.

I like to imagine them going back to the early days, Martin, when they started down this path with you. How they must regret their mistake!! It gives me such joy imagining their conversation, i.e. "what are we going to do with this Geddes fellow?!". I have posted this on FB for all to enjoy. You are a marvel, Martin, and I see great financial, as well as judicial, compensation resulting in due course. Get the bubbly ready!! :)

Martin, I have a question I have not seen you address before this. I know you have dealt with the non-court you. personally, have been dealing with. However, have you done any research to find out if this specific problem is only associated with North and West Cumbria or is in fact an issue in many other Local Justice Areas as well? If N&WC is the only instance, then this does not seem ultimately to be a general issue for your country. However, if other ghost courts do exist, it *is* a national and Constitutional issue.

Likewise, how similar is this issue to the weirdness you were subjected to in your Television invoicing from your local Council? It would seem to me that that situation is also national and actually similar, at least in concept.

I know focus is needed when developing a specific case, exactly as you have done with N&WC. However, once the case is fully processing, as it now appears to be in your case here, have you considered taking some time to see if you can prove that this is not just a one-off but is provably the case all over the country for both ghost court and ghost council billing and enforcement mechanisms?