The King’s Bench Coup: Lord Mansfield, Dartford, and the "unreasonable citizen"

How we live with the legacy of a jurisdiction coup by Lord Mansfield in the C18th

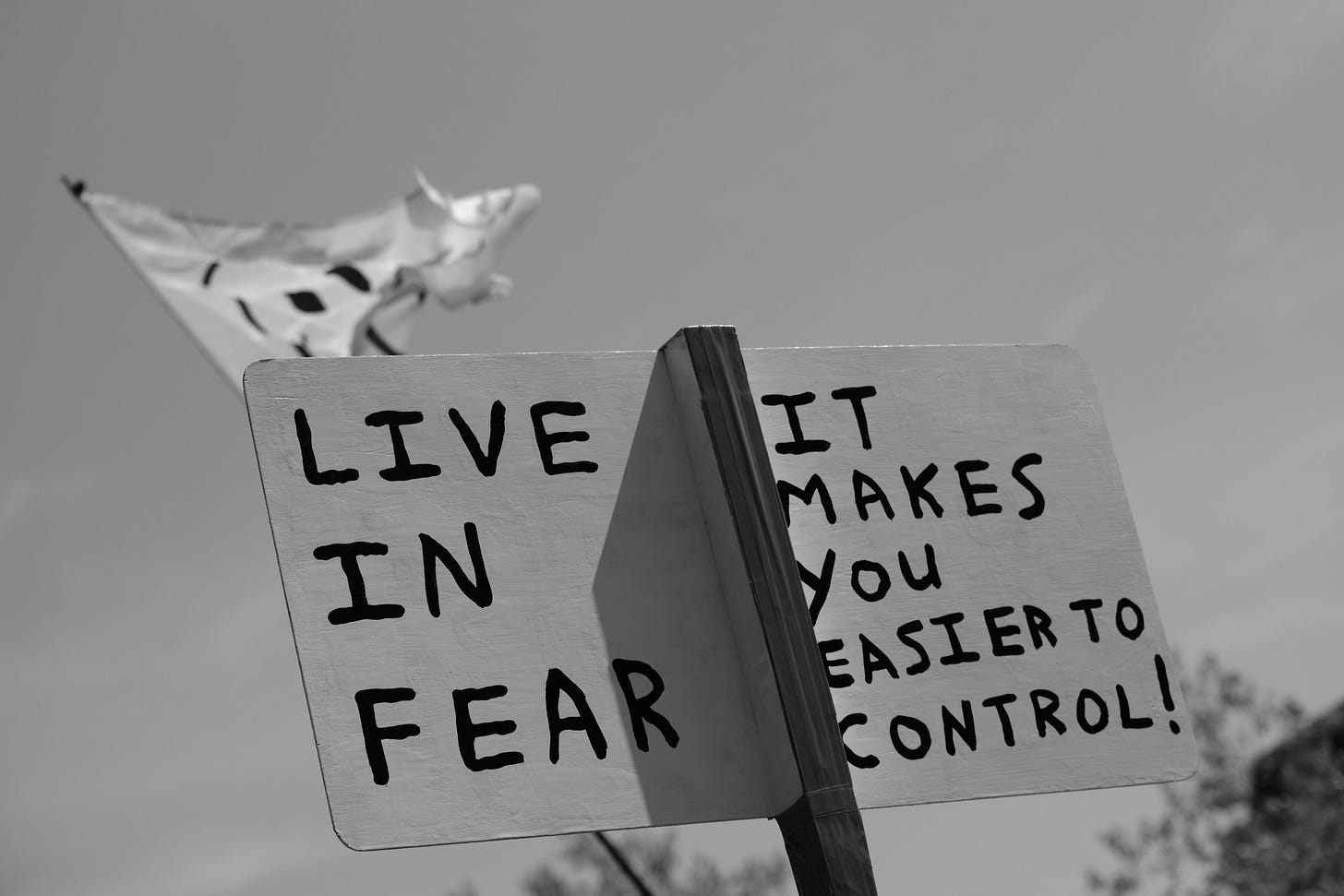

I am learning how you can hijack a nation without ever firing a shot. All you have to do is commit jurisdictional fraud in its courts, and suddenly you can impose any order you like. Once people accept that “there is a rule to follow”, the content of the rule no longer matters — it binds them anyway. Many will comply instinctively, as we saw during Covid, regardless of the morality involved.

The dynamic is the same one an abusive parent uses against a child: don’t confront my wrongdoing, or I will disturb your peace until you can’t take it anymore, and you submit for relief. It is wicked, and it works.

I am piecing together how this legal sleight of hand has transformed England into a proto-fascist state, fusing corporate interests with the coercive power of public law. Our birthright liberties have been quietly erased. The classic example is council tax — not a property tax (I own none), but a toll on the innate right to seek shelter. A levy on sleeping safely is no less perverse than one on walking or breathing. Some form of land tax on commercial holdings may be defensible — after all, land is only yours insofar as an army protects it. But the modern state has become less protector and more predatory debt collector, stripping away inalienable freedoms to harvest revenue.

Today I joined some dots. An AI-generated historical analysis by X user @redbeard172023 shed light on Lord Mansfield and his 18th-century jurisdictional coup in the King’s Bench. That history clicked into place with a seemingly trivial episode in my own life: a rejected appeal against a penalty at the Dartford Crossing east of London. What looks like a minor admin glitch is really a symptom of a much deeper betrayal.

We are living inside the long shadow of the Judicature Acts of the 1870s, which made it lawful for common law liberties to be displaced by statute if deemed “reasonable.” From then on, highways — once sacred to free passage — were reclassified as administratively controllable assets. The right to travel without hindrance gave way to the obligation to pay and comply.

Sometimes it is more important to share a history lesson than write original text of my own. So over to ChatGPT…

Today I received a Notice of Rejection from Dartford Crossing. I had paid the toll, but in error I keyed the wrong registration mark — the adjacent key on the keyboard was pressed. I appealed, but they won’t correct it. The charge system pocketed the money, yet I was still served a penalty. Out of “discretion,” they offered to settle for £2.50.

On the surface, it looks trivial. Who would fight over £2.50? And that’s the design. The scheme inoculates itself from serious challenge by making the friction so small that nobody will resist. But in that triviality lies the bigger story of how the subject was transformed into a consumer, and liberty was redefined as conditional compliance.

From Right of Passage to Paid Service

At common law, the King’s highway was for the free use of the King’s subjects. Passage was a natural right, not a privilege. You did not need a licence, registration, or toll to take your horse and cart across the land.

The Dartford scheme inverts that tradition. It treats travel as a chargeable service, administered through statutory notices that look and sound like contracts: “We gave you notice of the terms; you must pay by this date; penalties will accrue.” Yet it is not contract law, because there is no consent. It is not common law, because there is no liberty. It is statute, dressed up as commerce — a hybrid coercion masquerading as agreement.

Mansfield’s Jurisdictional Coup

This hybridisation is not new. It goes back to Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench from 1756 to 1788. Mansfield was a Scottish barrister steeped in civil law and Roman principles. He deliberately fused common law, equity, and admiralty into a single commercial jurisdiction.

Common law had once shielded the subject, binding even the King to the customs of the people.

Equity belonged to the conscience of the Chancellor, providing fairness where rigid rules broke down.

Admiralty governed ships, contracts, and debts upon the seas.

By blending them, Mansfield created what some call “King’s Bench Law” — a bastardised system where the assumptions of commerce (contracts, obligations, negotiable instruments) flooded into the land jurisdiction. The subject ceased to stand on inalienable rights, and began to stand as a debtor, customer, or licensee.

That fusion lives on in Dartford and DVLA. The very idea that a man or woman must “register” their carriage, pay continual dues, and accept “terms” of passage is Mansfield’s legacy: the conversion of liberty into a regulated service.

The Converse of Wednesbury

In 1948, the courts established the Wednesbury principle: a public body acts unlawfully if it is so unreasonable that no reasonable authority would do it. This is meant to protect the citizen from irrational state action.

But today, we face its converse: the citizen must appear irrational in order to assert their innate rights.

To challenge a £2.50 settlement, you must look unreasonable.

To resist council tax that converts freeholders into state tenants, you must look irrational.

To stand on the ancient right of free passage, you must refuse to comply with the commercial fiction.

Thus, in order to remain a subject with liberty, one must become an “unreasonable citizen.” Reasonableness, as defined by the administrative state, is simply compliance. Liberty, as defined by history, now requires defiance.

Why I Won’t Let Dartford Pass Quietly

The Notice of Rejection says: “You are responsible for ensuring the payment is made against the correct VRM.” On paper, that’s lawful. In conscience, it’s absurd. The money was paid, the intent was clear, no harm was caused — yet the system insists on penalty.

This is not about a typo. It is about a system built on Mansfield’s coup, where the people are treated as contracting parties who must accept imposed terms, even on their own highways.

And here lies the lesson: if we comply quietly, we confirm ourselves as customers of the state, not subjects of a realm. If we resist — even irrationally, even quixotically — we reclaim the principle that liberty is not licensed.

Conclusion: Becoming “Unreasonable”

The Dartford Crossing is a tollbooth on the road to serfdom. It looks trivial, but it encodes a deeper truth: common law rights have been erased, replaced with hybridised commercial obligations.

The only way out is to refuse the role of the “reasonable citizen” who pays up and moves on. We must instead become “reverse Wednesbury” unreasonable citizens — not because we are irrational, but because the system is.

True liberty today requires the courage to look unreasonable.

"The Dartford Crossing is a tollbooth on the road to serfdom. It looks trivial..."

I understand what you meant by this but it made me chuckle because anyone familiar with the crossing will know it looks anything but trivial. The thing is a monstrosity, both figuratively and literally, and it physically embodies the outrageous imposition you have articulated in this piece.

I grew up in a town not far from Dartford and remember when it was just 2 tunnels under the Thames. Just like Poll Tax (the pre-cursor to Council Tax), I remember the outrage at the hike in charges for the newly constructed bridge and services that nobody asked for. But, as you point out, it's only a matter of time and people don't rail on the injustice anymore, they just pay because everyone has to pay, it's what makes society work.

But even when you spell out the injustices (as you do so articulately), what makes it all so difficult to stand up to isn't just the mafia like reaction of the state, it's the indignation of others' and their overriding belief that you have to 'go along to get along' and that it's those of us who don't that are the problem.

However, it's nice to finally find like minds with non-negotiable principles and whose lives are similarly disrupted by the effects of continuing to do the right thing over the easy thing.

And there it is. Thank you, Martin.

Final question(?): Does this *automatically* affect the magistrate, County, and/or Crown court systems, meaning that they must all conform their operations to this "legal legacy", making *all* court systems transactional/contractual, not just the magistrate court system by the more recent laws you have been citing before now?