The Teesside test: exposing “admindiction” in the magistrates’ courts

Without constituting instruments, our lower courts cannot claim lawful authority

A friend of mine was recently summoned to Teesside Magistrates’ Court over a Council Tax matter. Beforehand, he lodged a jurisdictional challenge based on my “ghost court” research. On the day, he was left waiting while the bench spent 45 minutes reading his filing—plus three of my articles he attached. When they finally called him in, the case was adjourned for five months. One magistrate looked irate; another seemed puzzled and curious. Either way, the toothpaste is out of the tube: the “ghost court” issue cannot be put back.

HMCTS insists that magistrates’ courts don’t need to be properly named or constituted—claiming a “perpetual floating bench” suffices. But that position collapses against their own statutory rules, longstanding case law, international civil rights duties, day-to-day operational reality, and the ordinary practice of every other tribunal. The Single Justice Procedure, uniquely, issues documents in the name of IT codes rather than courts established by law. Jurisdiction is reduced to “the computer says so,” not the invocation of law. This isn’t down to frontline officials being lazy—it is the product of decades of poor governance of automation.

Because this filing got a tangible result, I am sharing it. You are welcome to adapt it for your own use. If you want the fully referenced version, ask me (or hit reply if you’re reading this via Substack). The material is in three parts:

A nutshell version, so you can grasp the issue in just a few paragraphs.

The filing itself, in more detail.

An afterword, reflecting subsequent research on this particular court.

The authorities never expected the public to conduct a forensic constitutional audit of court-naming practices using artificial intelligence. But anything incoherent, arbitrary, or irrational will now be exposed. This is only the beginning. There is no going back to the old way of doing things. For too long, criminal procedure has been misused—for social conformity (Covid lockdowns), for revenue generation (endless fines), and for morally dubious rules (notably Section 172). Those choices are now catching up with the system.

What follows is not legal advice. I am simply reporting what was filed and summarising the underlying hypothesis. Use at your own risk—and consult a solicitor if in doubt. Whether you agree or not, and regardless of what the law ultimately says, what this illustrates is that the playing field between the state and citizen has been levelled — in favour of the latter. The monopoly of the legal guild on deep statutory analysis of law has been broken.

Preamble

What you need to communicate to magistrates about court names and constitution

At the foundation of public law lies the distinction between law and arbitrariness. The gateway between them is establishment. A tribunal must, within the four corners of its initiating instrument, identify itself as a body established by law. This is not ornament; it is the juridical anchor that proves the tribunal’s constitutional existence before obedience is demanded. Without it, what issues is not law’s command but mere administrative paper. Article 6(1) ECHR crystallises this safeguard in requiring a “tribunal established by law” — a barrier against arbitrariness and self-will.

The Single Justice Procedure inverts this principle. SJP summonses are issued under inconsistent, invented labels that exist nowhere in statute. These are administrative fictions, not juridical anchors. They leave the tribunal unmoored, forcing the citizen to interpolate jurisdiction from IT codes and background statutes. Jurisdiction becomes a quiz, not a declaration. That is the essence of arbitrariness. Administration is supposed to facilitate law, not dominate it.

Jurisdiction cannot be guessed at; it must be declared. A summons must give the juridical answer, not a riddle. The House of Lords in Anisminic confirms that such defects are fatal: without a lawful tribunal invoked, everything downstream is null. Curative provisions (Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 s123, CrimPR 3.10) save only irregularities inside lawful proceedings; they cannot conjure jurisdiction where none was ever established. A summons that omits or obscures the court’s identity is void ab initio. The bridge from ordinary life to law was never crossed.

Comparative systems make the flaw obvious. Crown Court benches float across circuits, but always sit as “The Crown Court at [location],” a statutory entity under the Courts Act 1971. Courts martial convene anywhere, but always as “The Court Martial under the Armed Forces Act.” Employment Tribunals and Traffic Penalty Tribunals rotate members and venues, yet always act in the name of their statutory tribunal. Even private arbitral bodies like the Court of Arbitration for Sport maintain fidelity by naming the juridical body clearly. Floating benches are functional, not juridical. The tribunal’s identity is never improvised.

By denying the need for a juridical anchor, HMCTS has built arbitrariness into the SJP — the very opposite of law. As the process never establishes lawful authority up front, it cannot compel obedience. Establishment cannot be retrofitted; nullity cannot be cured. Other systems show the problem is solvable. Only the SJP chooses administrative fiction over juridical fidelity. The result is constitutional nullity: not jurisdiction, but admindiction — administration masquerading as law.

The Constitutional Illegitimacy of Teesside Magistrates’ Court

1. The Principle of Lawful Establishment

In the constitutional order of England and Wales, no court may exist merely by assumption, usage, or bureaucratic convenience. The rule of law requires that any judicial tribunal exercising coercive power over the public must be lawfully created by statute, charter, or other unequivocal legal instrument. The very concept of a “court” presupposes a valid chain of lawful authority traceable to Parliament, the Crown, or another recognised constitutional source.

Just as a birth certificate is the definitive record conferring legal recognition of an individual’s existence, and just as a registered vehicle identity arises from the lawful acts of a competent authority (DVLA), so too must a court have its own documented act of creation. Without such proof, there is no certainty that its jurisdiction exists in law. See also the natural-justice maxim from R v Sussex Justices, ex p McCarthy (“justice must be seen to be done”) which is engaged where the appearance of lawful foundation is missing.

Authorities: Courts are creatures of law; see statutory creations of the High Court (Senior Courts Act 1981), Crown Court (Courts Act 1971), Family Court (Crime and Courts Act 2013). Sussex Justices supports the proposition that even appearance defects taint outcomes.

2. Statutory and Constitutional Foundations of Magistrates’ Courts

Historically, magistrates’ courts were not free-standing corporate bodies; benches sat for petty sessional divisions. In modern law:

Courts Act 2003, s.8: England and Wales must be divided into Local Justice Areas by order of the Lord Chancellor.

The first LJA Order was SI 2005/554, which listed “Teesside” as an LJA (replacing the former petty sessions areas) and has been amended over time.

Courts Act 2003, s.10: lay justices are assigned to one or more LJAs (assignment can be changed).

Courts Act 2003, s.30: the Lord Chancellor (after consulting the LCJ) gives directions as to places, dates and times of magistrates’ sittings; the old statutory distinction of “petty-sessional court-houses” was swept away—jurisdiction travels with the bench.

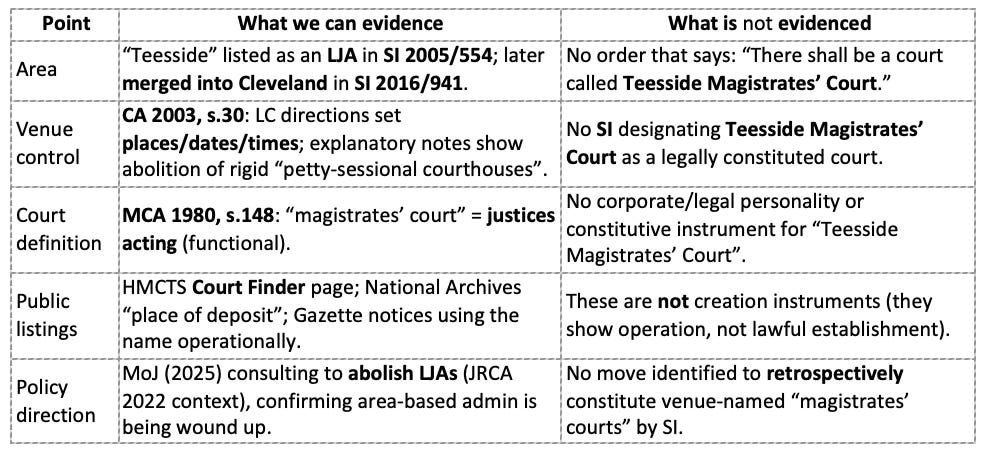

Crucially, these instruments create areas and allocate/seat justices, but do not create a named entity called “Teesside Magistrates’ Court”.

3. The Absence of Constitutive Evidence for “Teesside Magistrates’ Court”

No SI or Order in Council has been located that constitutes “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” as a court of law. (I checked the 2005 LJA Order and amendments; the 2016 LJA Order; Courts Act materials; and Gazette.)

What does exist: public-facing references confirming a venue and operational usage—HMCTS Court Finder page (address, codes), a National Archives “place of deposit” entry, and a Gazette notice that instructs objections to be sent to “Teesside Magistrates’ Court”. None of these are constituting instruments.

2016 LJA reorganisation expressly replaced “Teesside” and “Hartlepool” with “Cleveland” as the LJA from 1 April 2017. That confirms Teesside’s status as an area, not a court.

Inference: The area exists/existed (Teesside LJA → Cleveland LJA); the court as a named legal entity does not—it is a venue label governed by s.30 directions (which are not SIs and are generally not published as constitutive instruments).

4. Consequences of the Defect

If “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” has no lawful establishment instrument:

Proceedings are void (ultra vires): A tribunal must be established by law (Article 6 ECHR); decisions of bodies acting without jurisdiction are nullities (cf. Anisminic principle).

Personal/State responsibility can follow where coercive power is exercised without a lawful tribunal (jurisdiction cannot be cured by custom).

Rule-of-law legitimacy is compromised: the public cannot verify the court’s legal foundation in advance; at most they see a building and an HMCTS listing—not a constituting instrument.

These consequences are amplified by MCA 1980, s.148, which defines a “magistrates’ court” as the justices acting (a functional definition). In practice, that underlines the point: a named venue like “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” is not a legal entity created by statute; it is an administrative label for sittings directed under s.30 CA 2003.

5. The Analogy of Legal Identity

People (birth certificate), companies (certificate of incorporation), and even modern courts (e.g., Crown Court expressly created by Courts Act 1971, s.4) show the model: there is a point-of-creation record. By contrast, with Teesside:

There is no constituting SI naming Teesside Magistrates’ Court.

There was an LJA called Teesside (2005), but it was a statutory area, later merged into Cleveland (2016).

Venues and sittings are run by directions (s.30), not by naming/creating a “court”.

6. Stare Decisis, Per Incuriam, and the Duty Not to Disturb Settled Law

It is a fundamental maxim of the common law — stare decisis et non quieta movere — that the courts must stand by what has already been judicially determined and not disturb settled points of constitutional principle. This is binding and not subject to interpretation. The settled law is clear:

A court of law must be constituted by statute or charter. Jurisdiction cannot arise by assumption, practice, or administrative convenience. Without express statutory designation under the Courts Act 2003 or earlier enabling provisions, no magistrates’ court lawfully exists.

A tribunal acting without lawful constitution acts ultra vires. Its acts are not merely irregular but void ab initio (Anisminic v FCC [1969] 2 AC 147).

Public confidence depends upon visible legitimacy. In R v Sussex Justices ex parte McCarthy [1924] 1 KB 256, Lord Hewart CJ emphasised that “justice must not only be done, but must manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.” An institution that cannot demonstrate its statutory foundation fails this test.

Against this background, any judicial acceptance of Teesside Magistrates’ Court’s existence without the necessary proof would itself constitute a decision per incuriam — in ignorance of binding statutory provisions (e.g. Courts Act 2003, ss. 30–32) and controlling authority.

To persist in such error would not only be a dereliction of judicial duty but would also disturb the settled structure of English constitutional law. The maxims of stare decisis and per incuriam together reinforce the same conclusion: unless and until Teesside Magistrates’ Court demonstrates its lawful establishment, its decisions are nullities. To hold otherwise would destabilise the very system of precedent upon which our legal order depends.

7. Conclusion

On rigorous constitutional analysis, no public instrument can be shown that creates “Teesside Magistrates’ Court”as a court of law. The 2005 Order created/confirmed Teesside as an LJA (an area); the 2016 Order then replaced Teesside with Cleveland (again, areas).

The MCA 1980 s.148 and CA 2003 s.30 framework explains why: a “magistrates’ court” is the bench sitting, with venues set by ministerial directions, not a named corporate court.

Therefore: Unless HMCTS/MoJ can produce a constituting instrument (statute, SI, or prerogative order) naming and creating “Teesside Magistrates’ Court”, the body so-styled is not established by law. Under Sussex Justices, justice is not even seen to be done where a tribunal’s very existence cannot be shown; under Article 6 ECHR, a tribunal must be established by law. The present position leaves Teesside MC as a venue description—not a lawfully constituted court.

Side-by-side: what exists in law vs what’s missing

The Cleveland Angle

What Deeper Research Reveals

When Teesside was merged with Hartlepool in the 2016 reorganisation, the new “Cleveland Local Justice Area” appeared. From then, paperwork began to disclose a critical identity split: “Cleveland Magistrates’ Court (1460) sitting at Teesside Magistrates’ Court.” The code 1460 identifies Cleveland in national criminal-justice systems; the Teesside building is separately listed as venue code 1249. This dual identity is not trivial. It concedes that “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” is not a juridical body at all, but a building label where the Cleveland bench happens to sit.

The notices themselves reveal administrative sloppiness inconsistent with judicial acts. One adjournment letter gave two different phone numbers for the same venue. Another included a blank “Born:” field — a criminal template artefact in a civil liability case. Reasons for adjournment were reduced to dropdown stubs like “1. For the contested hearing” — not reasoned decisions. Summonses swung between “Teesside Magistrates’ Court” with and without an apostrophe, and carried no authorising name. All these defects echo an industrial mail-merge, not the solemn act of a tribunal established by law.

The deeper documentary trail is worse. Subject Access disclosures admit that councils prepare and serve the summonses and so-called orders, that no individual case file exists unless a matter is adjourned, and that liability orders are not produced by the court at all — councils hold them on their own computer systems. In other words, the court itself has no paper trail for the very orders it supposedly grants.

This is not just a 2025 discovery. Back in 2022, HMCTS staff confirmed in writing that “Cleveland Magistrates’ Court (1460)” was the administrative court code, and that notices were headed as Cleveland “sitting at” Teesside. The same correspondence included a hearing notice requiring someone “To Appear to Make Application” — when no application had yet been lodged. Staff went further: they told the party no liability order had been issued and that “liability orders are not made by the court.” Whether intended or not, these admissions reinforce the ghost-process thesis: administrative churn masquerading as judicial command.

The conclusion is clear. A tribunal that cannot keep its own identity straight, that relies on councils to generate its paperwork, and that cannot produce any authenticating record of summonses or orders does not meet the Article 6 standard of a tribunal “established by law.” What we have is admindiction — administrative process dressed up as jurisdiction. Under the Anisminic principle, such defects are fatal: proceedings are void from inception.

Fantastic work Martin. Going through the "legalese" would be a nightmare for me, you've made it understandable. I do wonder the reasoning for these changes back in 2003. Could this have been for future use by the EU on us British citizens? I recall 2 jaggs Prescot & his "devolution" of regions for use in a "federalism" system, which the EU desires. This does appear to be along the lines of "any court will do" as opposed to a British judicial law court, the ground work you might have just uncovered, not through their mistakes, but their future intentions. Thanks for all you do Mr Geddes 👊🤗

Brilliant, as always, Martin ! The fruit of your efforts is beginning to bloom. May it spread far and wide !