Yes, I loved Park Hill, but I wouldn't marry it

A Brutalist council estate highlights the spiritual struggle for Britain's urban soul

When I research my “deprivation photo walks” I may ask an AI chat engine to recommend me areas to consider, based on things like high-density modern architecture that is controversial. As a spur of the moment choice, based on such a suggestion, I took a two hour train ride to Sheffield to visit Park Hill, a famous brutalist council estate that looms above the railway station up on a hillside.

The estate has an iconic feature: a piece of graffiti that says “I love you Will u marry me” — that has been erased in a refit and replaced in neon. As it happens, if you need to ask a woman like this, it probably means you are operating in self-will, and the best you can achieve is a tolerable contracted matrimony, and not a covenantal marriage. As an emblem for the contradictory love we can have for such an extreme piece of modern architecture, it is befitting, even if the message is not entirely a conscious one.

Some of the estate has been demolished, but the majority of it remains — in a variety of levels of repair and renewal, from derelict to fully refurbished as student flats.

The renewed parts are colourful and clean.

The effect is nothing less than spectacular as an urban photography expedition, but would you want to live here? That’s harder to answer, as it is an easy walk to the city centre and many cultural, transport, and shopping facilities, as well as green space nearby. The dirtied surface of the buildings’ fabric facade isn’t the whole story.

Yes, some of the property is dilapidated and derelict, but that is because it is due for renovation. In a paradoxical way, the older units without modern coloured cladding are actually the most characterful, bearing the marks of years of occupation and weathering.

While it looks superficially similar to Broadwater Farm Estate in London, the atmosphere is far more welcoming. I had to go and walk the streets to feel it; it is an intuitive thing that cannot be divined in advance from researching statistics or reading maps. It isn’t alienating, as it is well-connected to the world around it.

The surrounding area is quite perplexing, as it has the Duke of Norfolk’s almshouses, posh stone family homes, and nice parks.

Traditional “red brick” northern style is all around.

You wouldn’t guess a cobbled street is around the corner from Park Hill.

There is plenty of similar modern architecture nearby.

To make sense of it all, there is an essential context of Sheffield having been an industrial city, famous for the rise and fall of the steel industry, akin to Pittsburgh.

Now it is doing a trade in scrap metal, not manufacturing.

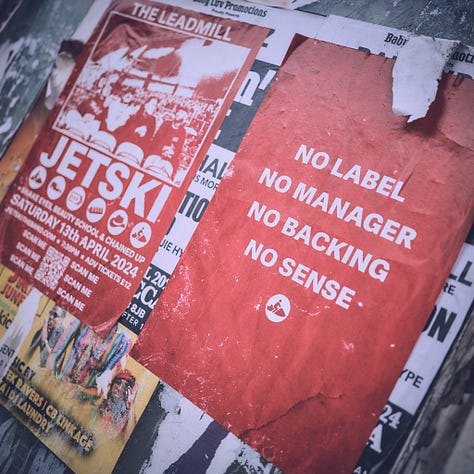

There is no lack of life in the city, that is for certain.

Sheffield has changed, and now is filled with temples from other cultures.

Along with a new demographic.

There is urban decay and renewal at the same time.

A pivotal part of the story is the decline of industry, particularly the miners’ strike in the 1980s, which I remember well. The Battle of Orgreave is a wound to this day.

I didn’t think I would like Park Hill, but it is a modern classic in its way, and in a weird way the ugliness of brutalism has elements of beauty too.

What I am finding is that notionally deprived areas are not necessarily “bad” places.

The Park Hill estate is far more memorable and worthy than many more modern but forgettable developments.

If you had to live here, it wouldn’t be a hardship. There may be some physical deprivation, but it is not a spiritually bankrupt place, and has endearing qualities.

The immortalised couple only stayed together three months, but their love lingers on.

Not quite marriage material, but Park Hill is loveable in its special way.

I’ve often been drawn to dilapidated areas. I used to dream I lived a trailer park by a freeway! God knows why. The aesthetic I cultivate iis far from it.

When I was a child, I visited my paternal grandmother every Sunday. She lived in a hugely deprived area in the Italian section of the Bronx in New York City. It was where my father had been raised and lived until he joined the US Army in preparation for WWII. We would leave our newly built, post WWII homestead in rural Long Island, New York and drive into the Bronx to visit with my widowed Nonna who lived in a tenement building, amongst dozens of other tenement buildings. It was a fearful place to me and, although I loved seeing my Nonna, I dreaded going because my parents would always send my brothers and I outside "to play". For a child who was used to being surrounded by green fields and nature, Nonna's habitat was alien. The only redeeming event was having Sunday lunch which I would help to prepare by removing the dried spaghetti dangling from the lines hung around her apartment. I know that the people who lived and worked in that area where Nonna lived were just hardworking, good people, in the main, yet there was, to me, a menace in the air. My soul could not accept that humans were meant to live this way. But, there was goodness and community there, evidenced by the way in which people shared what they had. My Nonna was always cooking for people, they were mostly her neighbors and her friends from Church, where she spent many hours, cooking and cleaning for the parish priests after my grandfather had died. Having lived in the community from the age of 15, when she married, until her death at 76, she would not have lived anywhere else. I think home and community is about the people who inhabit an area and there was much love where Nonna lived.