Designer hospitality in a post-human world

When systems exceed human limits, what do they owe the humans subjected to them?

It is the end of the first working week of 2026, and I have yet to “get back into the groove” of legal work and essay writing after the holiday break. My nervous system is telling me to slow down and take time to “find my skin” again after a socially intense few weeks over Christmas with family and friends. I have been travelling too: earlier in the week I made a tiring drive to London, and back to County Durham.

On the way home, Apple Music cued up a track I had not heard before. It grabbed my attention so completely that I swapped from maps to music on the motorway to note its name, memorised it, and wrote it down at the next stop. From that single piece unfolded a deep musical exploration and an unexpected “aha!” moment about my legal work — an artistic and intellectual side-trip that absorbed me for days.

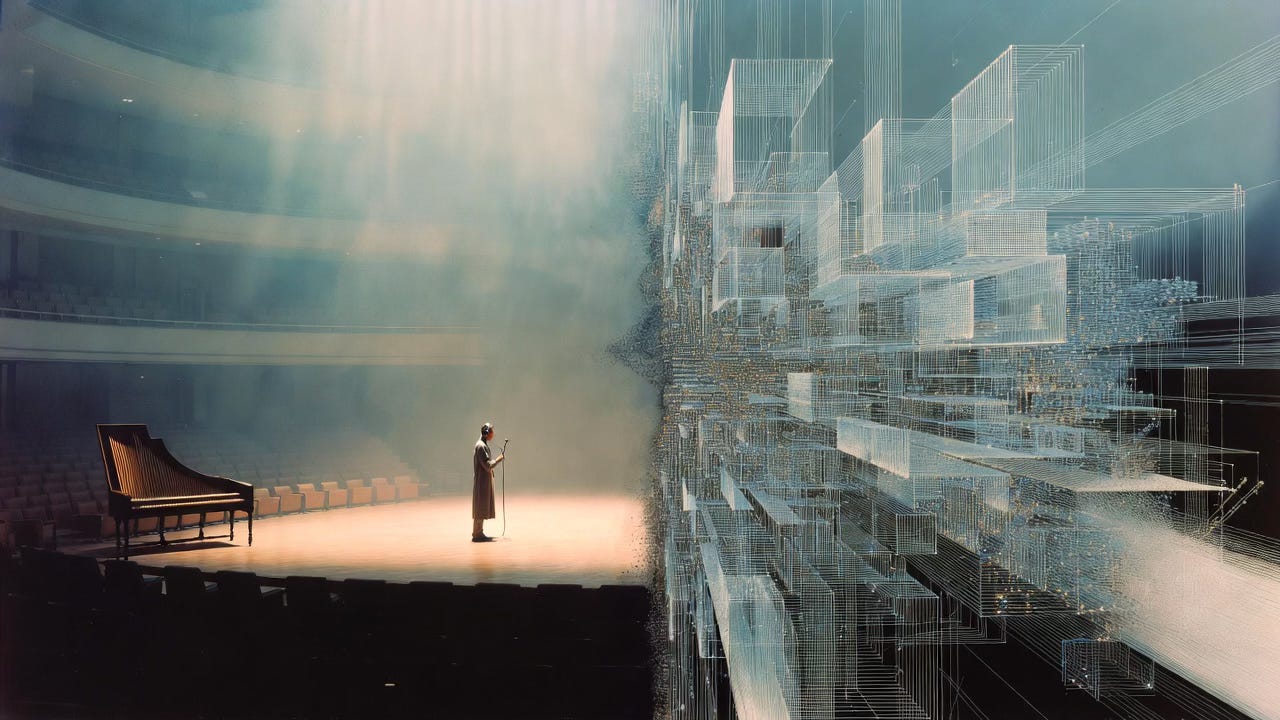

The punchline up front is this: music made with machine automation can readily exceed what a human can physically perform. Once it does, design choices determine how listenable the result is to the human nervous system — the hospitality of the piece. A low-hospitality work can still be recognisably music, even if it no longer delivers automatic pleasure through harmony or groove. Other systems — including law — are now being automated using post-human tools. In those systems too, choices are being made about hospitality.

The starting point for this reflection was Amon Tobin’s Mission from the album Bricolage. What I admire about it is how a simple, enjoyable melodic figure is embedded within an extremely complex, syncopated beat system — one that cannot be denoted, rehearsed, or performed by a human using traditional conservatory methods. Whether you enjoy such pieces is beside the point; they serve only to illustrate a spectrum of hospitality.

Here, hospitality means the degree to which a system remains intelligible, orienting, and trustworthy to a human participant when operating near — or beyond — human limits.

Let’s start our journey with a high-hospitality piece of electronic music.

The Doctor Who theme is among the most recognisable pieces of electronic music ever written, and one of the earliest composed specifically for television. Masters of rave craft and crowd synchrony, Orbital have transformed it into a closing act capable of crowning a night of collective revelry.

In their Glastonbury Festival performance, a euphoric surge roughly three minutes in is paired with synchronised lasers to produce a whole-body experience. The result is engineered joy: extreme scale and massive technical power, deployed in a way that remains inviting rather than overwhelming. The system exceeds the individual, yet carries them.

This Orbital performance exemplifies raw power expressed with hospitality intact. Despite its scale, it remains legible, orienting, and participatory — engaging the listener not as a subject to be acted upon, but as a consenting partner in the experience.

Now let us move to the hospitality edge case: Vordhosbn by Aphex Twin — Richard D. James, the self-taught Cornish master of digital deviance. There is no traditional harmony, no familiar progression, no phrasing drawn from what we usually recognise as “normal” music. Instead, there is a torrent of glitches, structures, and tones. Yet the piece has a recognisable and internally consistent texture that is, in a quiet way, endearing.

On first listen it can feel like being politely assaulted. On repeated listening, however, something different happens: the listener’s capacity expands to accommodate its playful transitions in and out of overload. The work knowingly operates at the boundary of hospitality — that is the point, and the source of its genius.

Vordhosbn exceeds what a human can physically perform and consciously parse, yet its grammar remains intact. Meaning is felt rather than decoded. The listener is stretched, but not abandoned. It stays just on the hospitable side of hostility: hospitality may approach zero, but it never becomes negative. Even as familiar perceptual frameworks begin to break down, the experience remains safe and lawful — coherent, intentional, and trustworthy right up to the edge.

Are you ready for some genuinely inhospitable music? The exemplar I have chosen is Gantz Graf by Autechre. I have deliberately not selected repetitive Berlin techno — where the aim is hypnotic absorption rather than inhospitability — nor a “knowing” assault on the senses such as Frank Zappa’s Jazz from Hell. Instead, this is a tightly orchestrated nervous breakdown of sound, operating at the far limit of what can still be recognised as music before it collapses into noise.

Unlike the Aphex Twin example, Gantz Graf makes no allowance for whether its structures can be absorbed by the human body. There is no attempt to train the listener, no gradual acclimatisation, and no invitation to participate. The work exhibits extreme structural intelligence combined with minimal concern for listener orientation. There are no melodic or emotional handholds — only a direct confrontation with sound. The listener is not carried, but exposed.

One could almost imagine feeding this piece into an artificial intelligence and asking it to judge whether it is technically accomplished or aesthetically valid, precisely because its evaluability does not depend on human embodiment. While the music is not violent in any literal sense, consent has been effectively erased. Hospitality is not merely close to zero; it is explicitly not a design goal. One step further and extreme rampage would degenerate into auditory rape; this is the lower limit of hospitality that is still discernibly musical in nature, even if objectionable to many listeners.

These degrees of hospitality have a clear musical pedigree and are not confined to any one set of eclectic or peripheral tastes. In exploring them, my recommendation engine surfaced a range of composers and artists — some unfamiliar to me, others well known — spanning different traditions and eras. What follows is a more conservatory-grade taxonomy of hospitality, offered to show that the same design question translates cleanly across registers of musical practice, before it is transplanted into a different domain altogether.

As a totem of high hospitality, consider Brian Eno’s 1983 work An Ending (Ascent) — by a very familiar artist. The listener fits entirely within its frame, free to enter, leave, or remain without penalty. Everything is immediately legible; no perceptual boundaries are pushed, yet a gently evolving texture sustains attention over time.

In energy, it is the opposite of Orbital, yet the kinship is clear. Both generate uplift — one through stillness, the other through force — demonstrating that hospitality is not a function of intensity, but of orientation.

Mirroring Aphex Twin’s Vordhosbn, we have György Ligeti’s 1968 work Continuum. It pushes the harpsichord to its limits as an instrument, as well as the listener, while breaking neither. Both pieces explicitly push event density beyond perceptual resolution, with individual notes dissolving into texture even as musical grammar remains intact. The listener experiences a boundary breakdown without total collapse.

Lastly, as a counterpoint to Autechre, consider Conlon Nancarrow’s Study for Player Piano No. 37, composed for machine in the late 1960s. Its temporal ratios exceed anything a human performer could realise, and strain the listener’s capacity to parse what they hear. The listener is not expected to follow the music in any conventional sense; beauty still emerges, but hospitality is incidental rather than designed.

This stands in direct contrast to Orbital, where the experience is explicitly shared. Here, the music is not collaborative but imposed: opaque, indifferent to participation. The listener is not carried, but subjected. The power of the piece lies precisely in its refusal to accommodate — the erasure of hospitality is not a failure, but the point of the exercise.

Lying in bed with my earbuds in, I had the moment of insight: the motif of hospitality translates directly from music to my legal work. I am being presented with court names that cannot be parsed as courts, and are not legible as law. Just as electronic music and laser shows enable post-human performance, so too do modern legal systems. The risk in both domains is descent into brittle abstraction — which is why electronic artists like Shpongle mix flute with sequencers, grounding the result in human flesh through breath.

When I review the dozens of names used to assert legal authority in my case, what emerges is not merely multiplicity, but a graduated withdrawal of hospitality as authority becomes more abstract, automated, and throughput-oriented.

At the Orbital/Eno tier sits Carlisle Magistrates’ Court. It is singular, embodied, and locatable. A human can orient themselves without specialist decoding. In hospitality terms, the citizen fits entirely within the frame. Authority is legible, consent to jurisdiction is meaningful, and participation is possible. This is law as invitation: it may be contested, but one knows where one stands.

Crossing into the boundary case — analogous to Aphex Twin or Ligeti — we encounter North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court sitting at Carlisle. Names become composite and aggregated. Intelligibility is still recoverable with effort: event density exceeds intuitive parsing, yet sufficient grammar remains intact for the system to function. Hospitality is depleted but not withdrawn; the result remains lawful, in the same sense that boundary music remains listenable.

At the far extreme lies inhospitability, exemplified musically by Autechre or Nancarrow. This maps onto abstracted, ghostly, or non-determinate courts that cannot be meaningfully located or oriented to. Here we see numeric identifiers, inconsistent naming across documents, and authority inferred from output alone. This is where “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)” belongs. Correctness is internal to the system; human orientation is incidental.

The crux is that these are distinct categories of human endeavour:

Low hospitality in music is legitimate because no coercion follows, withdrawal is allowed at any moment, and consent is optional as a result. In contrast,

low hospitality in law is illegitimate because coercion follows automatically, withdrawal is punished, and consent is presumed — not earned.

That’s the ethical asymmetry. My stress-test via the High Court shows the system will break the rule of law (“musical listenability”) before it breaks throughput. Translated into the hospitality frame, the higher purpose it serves is preservation of output, volume, efficiency — not legibility, traceability, or demonstration of authority. That is exactly the Autechre or Nancarrow posture: “The system runs. Whether you can follow is not our concern.”

When courts move from named places to abstract identifiers, they undergo the same transition as music moving from Orbital to Autechre: power increases, hospitality collapses, and authority is inferred from output rather than demonstrated through intelligibility. When legal systems become post-human — as with the Single Justice Procedure, automated, high-throughput, and abstract — they therefore face the same hospitality question as post-human music, but with coercive consequences.

The doctrine implicitly offered by the State might be caricatured as “if it makes any sound at all, then it is law”, though that formulation misses some nuance. More accurately, in a low-hospitality legal system, output is mistaken for authority: if the system produces any paperwork, it is treated as lawful by default, regardless of whether its origin, structure, or jurisdiction remains intelligible to the person bound by it.

On this basis, ghost courts can be reclassified as low-hospitality systems. Tribunal identity is unclear (the genre is undefined); authority is inferred rather than demonstrated (the listener cannot locate the work); and objections are treated as noise (like a phone ringing during a concert). Just as Orbital protects the listener, and Aphex Twin protects correctness, Autechre protects the system itself. The claim advanced here is that when legal machinery protects throughput over hospitality, a point is reached at which it ceases to function as law — just as sound, pushed far enough beyond grammar, ceases to function as music.

Post-human systems are not the problem. We have lived with them in music for decades, and learned to distinguish those that stretch us, those that abandon us, and those that carry us safely beyond ourselves. The ethical question is not whether a system exceeds the human, but whether it remains accountable to them. Music that abandons the listener merely loses an audience. Law that abandons the citizen loses legitimacy.