MoJ FOIA: not quite proof, not quite vibes

What the Single Justice Procedure reveals about custody and attribution

I recently published two articles that serve as the conceptual groundwork for today’s analysis of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) response from the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) concerning fines under the Single Justice Procedure (SJP). While the SJP by itself can’t send someone to prison — its outcomes feed into enforcement that can.

Together, those pieces introduced and developed the ∆∑ attribution framework. The purpose of that framework is simple: to reattach accountability to named actors, or to demonstrate where authority becomes diffuse — where power is exercised without clear traceability to a defined decision-maker.

The first article, “The Attribution Wars,” set out the larger problem. Much of what passes for debate about “truth” misses a prior step. Before assessing whether an act is justified, lawful, or fair, one must identify where attribution (who decides?) terminates — both conceptually and operationally. If the actor is unclear, the inquiry is already degraded.

The second article, “The mother of all AI audits,” explained why this matters now. AI has collapsed the cost of identifying and reopening attribution gaps. What previously required months of sustained effort can now be pursued with precision and persistence.

This article moves from model to specimen. It applies the framework to a specific FOIA response from the MoJ. The response is interesting in its own right. More importantly, it serves as a worked example of how degraded attribution appears in practice — and how it can be examined without drama or overreach.

This case study is British, but the dynamics are not. I am using the UK as a test case because its process-native system makes attribution questions unusually visible. The underlying pattern — automation, delegated authority, administrative enforcement, and the gap between procedural compliance and proof-level anchoring — exists in every advanced democracy. The labels differ. The logic travels.

“Ghost courts” and attribution gaps

The immediate context for this FOIA request is my long-running attempt to clarify what I have described as “ghost courts” in England and Wales — legal identities under which convictions are issued, yet whose statutory creation, jurisdictional anchoring, and institutional accountability are not readily identifiable in primary legislation.

What began as a jurisdictional dispute has matured into a deeper attribution question:

If a conviction is issued, there must be a legally constituted court.

If a fine is imposed, there must be a judicial act traceable to a named office-holder acting under defined statutory authority.

If enforcement escalates to imprisonment for non-payment, the paper trail must ultimately lead back to a lawful court and a demonstrable exercise of judicial power.

The concern is not rhetorical. It is structural.

The Single Justice Procedure (SJP) was introduced to streamline high-volume, low-level criminal cases. In practice, however, its documentation often refers to administrative constructs and composite labels rather than to clearly constituted courts established in statute. Authority appears implied through process rather than explicitly anchored to a recognisable judicial body.

That distinction matters — because administrative labels cannot substitute for judicial acts.

The logic of habeas corpus is unforgiving: detention must rest on a clearly attributable judicial act. Liberty cannot be curtailed on the basis of automated workflow, institutional shorthand, or procedural implication. If the authority chain cannot be explicitly traced, the attribution is degraded.

This FOIA request seeks to test that chain — not as theory, but in relation to specific SJP fines and the enforcement pathway that follows.

Why this FOIA response matters

The stress-test case is not a “pure” SJP conviction, nor a classic contested magistrates’ court hearing.

In a classic hearing, the attribution chain is visible: a recognised court, an identifiable judicial office-holder, a hearing in open court, and a traceable judicial act.

In a pure SJP case, the paper record is at least internally coherent: a single justice determines the case on the papers.

But the Single Justice Procedure applies only to summary, non-imprisonable offences. A single justice cannot impose custody as a sentence. The liberty risk arises downstream: where a fine imposed on the papers later enters the enforcement pipeline, and non-payment can culminate in committal to custody. Committal orders do not always result in imprisonment, but they are the formal gateway to it.

The real stress point therefore lies in the hybrid pipeline — where proceedings begin under the Single Justice Procedure but later transfer into a conventional hearing, while enforcement continues.

In such cases, sanctions can escalate — including committal to custody — yet the provenance of authority can become blurred:

Is the fine treated as arising from a paper conviction by a single justice, or from a later hearing in open court?

Which court identity is treated as the originating authority?

Which judicial act is treated as grounding enforcement?

This matters because habeas corpus is not a metaphor. It is a structural demand: detention must rest on a clearly attributable judicial act. If a custody pathway can be traced through procedural continuity but not anchored to an identifiable termination object, the constitutional safeguard is weakened — not by defiance of law, but by diffusion of attribution.

No one is suggesting that imprisonment presently rests on “vibes.” But when proof-level anchoring is not demonstrable at system scale, the trend line runs in that direction at system level — from receipts to convention, from convention to assumption.

That trend is constitutionally risky in the context of imprisonment and loss of liberty.

Truth vs termination questions

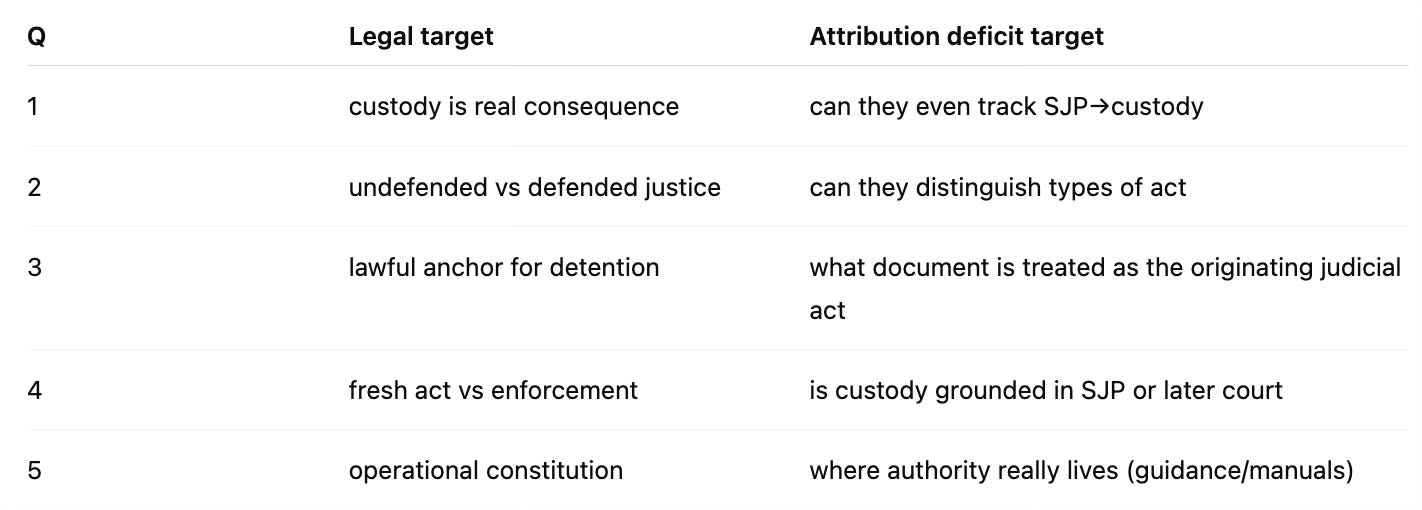

I asked five questions about fines imposed under the Single Justice Procedure (SJP), where cases are determined on the papers by a single justice of the peace.

Before looking at those questions, one qualifier matters. It is not decorative. It is the point.

For the avoidance of doubt, this request relates only to fines imposed following convictions obtained under the Single Justice Procedure and should not include or aggregate data relating to fines or committals arising from non-SJP proceedings.

The legality of “classic” magistrates’ court hearings is not in doubt in this context, because the attribution chain is clean: a recognisable court, a named judicial office-holder, an identifiable hearing, and a traceable judicial act grounded in statute.

The problem I am testing for is what happens when that chain is degraded by automation — and, in particular, in hybrid cases (including my own) where proceedings begin under the SJP but later transfer into a conventional hearing.

That is where attribution becomes ambiguous: the process continues, enforcement proceeds, but the anchor for the judicial act can become implied rather than explicit.

Each question is deliberately dual-purpose.

At the surface level, it engages the legality of the Single Justice Procedure and its enforcement consequences.

At a deeper level, it tests where attribution terminates — what object, act, or office-holder is treated as grounding authority, and whether that anchor is explicit or merely implied.

In the ∆∑ framework, termination of inquiry can occur in any of four modes: (F) formal proof; (PF) procedural flow; (RL) rhetorical laundering (legitimacy-by-language); or (I) institutional override. Restated colloquially, these are “receipts”, “convention”, “vibes”, and “force”.

This distinction of truth from termination is the teachable moment — and I am presenting it up-front, before turning to the details of the questions and responses:

If nothing else, the takeaway is this:

behind every “truth question” sits a prior “termination question.”

Before you can argue about whether something is justified or lawful, you must identify where the system has decided the inquiry stops.

The audit skill is to manage both in synchrony.

Q1&2: When the system cannot isolate its own pipeline

The first two questions naturally form a pairing. (I have rephrased the FOIA questions slightly for an essay audience to make the language less technical.)

Q1: How many people have been committed to custody for non-payment of a fine where the fine arose from a conviction obtained under the Single Justice Procedure (SJP)?

Q2: Of those, how many arose from:

undefended SJP proceedings; and

defended proceedings that transferred out of SJP?

Legal target

To establish whether deprivation of liberty is, in practice, occurring downstream of SJP-originated convictions — and whether it arises predominantly from paper convictions (undefended) or from cases that later moved into conventional hearings.

Attribution target

To test whether HMCTS/MoJ can maintain a traceable enforcement chain between:

SJP conviction → fine → non-payment → committal to custody

If the state cannot even quantify custody outcomes arising from SJP fines, then attribution is degraded at the most basic level: outcome accountability.

MoJ response

In regard to questions one and two above, we can confirm that the MOJ does not hold any information in the scope of your request. Whilst the MOJ holds data on the volume of committal orders issued by the courts for nonpayment of court fines, the MOJ has no way of determining how many of those fines were imposed following a conviction obtained under the Single Justice Procedure. If held, the information could only be obtained by accessing the case records themselves which are held in the custody of the court for the purposes of the court, only. That information required to respond to your request therefore is not held by the MoJ, and so not subject to the FOIA.

It may help to explain that a defendant who has been issued with a committal order by the courts may still avoid imprisonment if the debt is subsequently settled.

The FOIA does not oblige a public authority to create information to answer a request if the requested information is not held. The duty is to only provide the recorded information held.

What was supplied?

A statement that total committal-to-custody figures exist, but are not classifiable by SJP origin.

An explanation that SJP provenance is not recorded in a way that permits identification of committals.

A refusal based on the FOIA cost limit, due to manual checking.

No numbers were provided for SJP-linked committals, and no breakdown was possible.

What category did they terminate in? (F / PF / RL / I)

Termination is primarily PF.

The MoJ does not dispute the legitimacy of the question, nor deny that committals occur. Instead it terminates inquiry at the procedural layer:

“we don’t record it that way”

“it would require manual checking”

“that exceeds the statutory cost limit”

This is a classic PF termination: procedural constraints substitute for proof-level traceability.

Any load governor invoked?

Yes — explicitly. The MoJ relies on ‘not held’ and manual inspection constraints.

Where did attribution stop?

Attribution stops at the point where the system is asked to link:

custody outcome ↔ SJP origin

The MoJ position is effectively:

custody outcomes are recorded,

SJP convictions are recorded,

but the system does not maintain an explicit join between them.

So the termination object the request seeks — a traceable custody pipeline originating in SJP — is not available at proof-level (F).

Instead, the system terminates at process:

“We can’t tell you, because we don’t hold the data in that form, and it is too costly to reconstruct.”

This is the first major specimen of degraded attribution: not a disputed legal principle, but an operational inability to attach a liberty outcome to a specific adjudication pathway.

Q3. Identifying the judicial act behind committal

The next question drills down from aggregate numbers into the authority for a singular case.

Q3: In cases where committal to custody follows non-payment of a fine imposed under the SJP, what document or record is treated operationally by HMCTS as the originating judicial act grounding committal?

And specifically, is it:

the original SJP conviction record;

a later court order or warrant; or

some other record?

Legal target

To identify what legal act is treated as the formal foundation for imprisonment. In constitutional terms, this is the habeas corpus question: What is the judicial act that authorises detention?

Attribution target

To test whether custody is anchored to a traceable judicial act — and whether that act is:

clearly attributable to a court and decision-maker, or

treated as an implied continuation of automated process.

This question is designed to force the system to name the “termination object” for liberty deprivation.

MoJ response

In regard to question three above; we have interpreted this question to mean the records used that led to the judicial decision to commit an individual to custody. If held, this will form part of the court record. The information you require to answer this question could therefore only be obtained by accessing the case records themselves which are held in the custody of the court for the purposes of the court, only. That information required to respond to your request therefore is not held by the MoJ, and so not subject to the FOIA.

The FOIA does not oblige a public authority to create information to answer a request if the requested information is not held. The duty is to only provide the recorded information held.

It may be helpful to explain that the decision to commit an individual to custody is an exclusively judicial function of which the judiciary retain independence. There are sentencing guidelines which explain the options available to the judiciary regarding their decision which can be found at the following link: Sentencing Council

What was supplied?

A refusal to identify the originating judicial act.

A procedural explanation: the answer would require case-by-case file inspection.

No document type, no operational description, and no standardised “anchor object” was provided.

What category did they terminate in? (F / PF / RL / I)

This is again primarily PF termination. But it is more revealing than Q1/Q2, because the question is not statistical. It is conceptual and operational:

“What do you treat as the grounding judicial act?”

The MoJ’s response indicates they are not in a position to name a general operational rule — and instead terminate at procedural retrieval constraints.

Any load governor invoked?

Yes. Again, the FOIA cost limit is the load governor: answering would require manual searches of case files. This is a recurring “load governor” in these responses: the claim that answering would require manual inspection of individual case files.

That defence is procedurally valid under FOIA. But it also reveals something structural. HMCTS can record committals. It can record SJP convictions. Yet it cannot answer basic provenance questions without treating each case as a bespoke manual audit.

In a paper world, that might be an unavoidable constraint. In a process-native justice system — and especially in an era where AI has collapsed the cost of classification, retrieval, and linkage — it looks less like an inevitability and more like an architectural choice.

In other words: the “cost limit” does not merely terminate the FOIA request. It exposes the absence of proof-level joins in the underlying system.

Where did attribution stop?

At the point where the system is asked to explicitly identify the judicial anchor for imprisonment.

The practical termination is:

“We cannot (or will not) specify what grounds custody, without inspecting individual cases.”

This is a highly consequential attribution break, because it means that, at the institutional level:

committal to custody is an operational pathway,

but the originating judicial act grounding it is not articulated as a standard termination object that can be disclosed, described, or audited at scale.

In ΔΣ terms, the system is declining to provide an F-mode anchor for the custody pathway (mandatory for habeas corpus), and instead terminates inquiry at PF via cost and retrieval constraints.

Q4. Fresh act or residual authority?

The next question tests the continuity of authority between the single justice procedure and any committal to prison for non-payment of a fine.

Q4: For administrative and enforcement purposes, is committal to custody for non-payment of an SJP fine treated as:

enforcement of the original SJP conviction; or

arising from a fresh judicial determination at a later hearing?

Legal target

To determine whether imprisonment is treated as:

a continuation of the original SJP conviction, or

the product of a distinct judicial act occurring later in time.

This distinction matters because if committal is a fresh judicial act, it must be grounded in a recognisable court and identifiable judicial decision.

Attribution target

To test whether custody authority:

flows automatically from the SJP conviction, or

is re-anchored to a new judicial act with its own termination object.

In ΔΣ terms, this asks: Where does authority for detention terminate — in the original paper conviction, or in a later act?

MoJ response

Unlike Q1–Q3, the MoJ did provide a substantive answer.

In regard to question four above, this question does not fall under the FOIA legislation, as it is not a request for recorded information as described by the FOIA. However, we can advise that it is a fresh judicial determination

This is common in FOIA practice: a question can be outside FOIA as a request for recorded information, but still answered informally.

What was supplied?

A clear classification.

No cost-limit refusal.

No “not held” response.

They affirmatively state that committal is treated as a fresh judicial determination.

What category did they terminate in? (F / PF / RL / I)

This is closer to F, but only at a classificatory level.

They provide a categorical description of how committal is treated operationally. However, they do not identify:

the specific court,

the form of order,

the warrant type, or

the document treated as the anchor.

So while this is more concrete than Q1–Q3, it is still not full proof-level disclosure of the grounding act.

Any load governor invoked?

No. This is a direct answer.

Where did attribution stop?

At the level of abstract characterisation. The MoJ confirms that custody does not automatically enforce the original SJP conviction. Instead, it is said to arise from a new judicial determination.

That answer has two immediate implications:

The authority for detention is not implied to flow automatically from the paper SJP conviction.

There must therefore exist a later judicial act that grounds imprisonment.

However, Q3 established that the system cannot readily identify, at scale, the specific document treated as the originating judicial act.

So we now have a structural tension:

Q4 asserts that custody rests on a fresh judicial determination.

Q3 indicates that the originating judicial act grounding custody cannot be specified without manual file inspection.

In attribution terms, authority is said to re-anchor — but the anchor object itself is not made explicit at system level.

That gap is operational and affects real lives.

Q5. Where authority actually lives: the guidance layer

To close, we ask what operational guidance, manuals, and training underpin this approach.

Q5: Provide copies of (or extracts from) any current or previously operative internal guidance, policy documents, manuals, or training materials held by HMCTS that address committal to custody following non-payment of fines imposed under the SJP.

Legal target

To identify what operational rules govern the custody pathway when an SJP fine is not paid.

In practice, committal is not managed by statute alone. It is implemented through guidance: who does what, which forms are used, what steps are required, and what documentation is produced.

Attribution target

To determine where real authority “lives” in the enforcement pipeline.

If the system cannot provide proof-level answers about committal outcomes or anchoring documents (Q1–Q3), then guidance becomes the next best proxy for the operational constitution: the real mechanism by which authority is applied.

This question tests whether custody is grounded in:

explicit statutory objects, or

internal procedural objects.

MoJ response

In regard to question five above, Committal for non-payment of fines is the same procedure for the Single Justice Procedure as any other fine in criminal proceedings. MOJ/HMCTS holds some material comprising guidance to legal advisers concerning commitment for default. Training materials for legal advisers on fines enforcement are not held by MOJ/HMCTS but by the Judicial College, which is not an authority for the purposes of FOIA.

Please find attached the following documents for your information:

Calculating Terms in Default: https://intranet.justice.gov.uk/documents/2017/05/calculating-terms-in-default.pdf

Fine days in default calculator: https://intranet.justice.gov.uk/documents/2019/09/fines-days-in-default-calculator.xlsx

Partial Commitment (Also known as split enforcement): https://intranet.justice.gov.uk/documents/2017/05/partial-commitment.pdf

For guidance on how to structure successful requests please refer to the ICO website on the following link: https://ico.org.uk/your-data-matters/official-information/

No such documents were attached to the reply. These intranet links lead to a login page that appears restricted to MoJ staff. Either the documents exist and were not supplied, or they do not exist — and both possibilities are informative.

What was supplied?

A denial that SJP-specific committal guidance exists.

A procedural explanation: committal is a later hearing and not SJP-specific.

Links to general fine enforcement guidance and public-facing documents.

A “not held” response in respect of Judicial College training material.

So unlike Q1–Q3, this question produced actual artefacts — but not the ones requested.

What category did they terminate in? (F / PF / RL / I)

This is a mixed termination.

The claim “no SJP-specific committal guidance exists” is a PF termination: the process is treated as generic fine enforcement once it reaches committal.

The Judicial College point is PF by way of “not held” — a boundary termination object (“outside our organisational possession”).

The links provided are F-lite: documents exist, but they are not the specific internal materials requested, and are not accessible directly.

Any load governor invoked?

Not cost. The governor here is instead:

scope and institutional boundary (“not held” because Judicial College is independent).

This is a different kind of governor: not economic load, but organisational segmentation.

Where did attribution stop?

At the boundary between:

SJP as a conviction mechanism, and

committal as a generic enforcement mechanism.

The MoJ response effectively asserts:

“Once committal is in view, the system no longer treats SJP provenance as a meaningful category.”

This aligns with Q1/Q2, where the system cannot isolate committals arising from SJP fines.

And it aligns with Q4, where committal is treated as a fresh judicial determination at a later hearing.

But it also produces a revealing institutional fact:

Judicial training materials relevant to committal are outside HMCTS’s FOIA reach, because they are held by an independent body.

So even where committal involves judicial discretion, the training and doctrinal materials shaping that discretion are structurally insulated from disclosure via HMCTS.

In attribution terms, the system provides general enforcement documentation, but the SJP-to-custody chain remains untraceable at proof level, and part of the practical operational constitution is placed outside the FOIA boundary.

Synthesis: What this FOIA reveals

Taken together, these responses reveal not a single refusal, but a pattern. It is not “vibes.” But it is attribution by institutional implication rather than system-level proof. That is a problem in liberty-protection terms.

Imprisonment is supposed to run on hard proof of authority — something closer to mathematics: explicit derivation, named actors, traceable acts, clean termination points. Instead, what appears at system level is closer to history (this is how it has evolved), theology (authority asserted through institutional creed), or drama (roles performed within a procedural script).

There is nothing wrong or lesser with these disciplines. They simply do not match the problem domain. Deprivation of liberty is not a narrative exercise. It requires proof.

1. The system records outcomes — but not provenance

The MoJ can record committals for fine default. It can record convictions under the Single Justice Procedure. What it cannot do is join the two at system level.

This is not an absence of data. It is an absence of maintained provenance.

Where liberty is concerned, provenance is not a luxury feature. It is the constitutional spine of enforcement. A system that cannot demonstrate the lineage of its custody decisions at scale relies on institutional coherence rather than auditable linkage.

That is a design choice — and an uncomfortable one.

2. Authority is asserted — but not systemically articulated

We are told that committal rests on a “fresh judicial determination.”

That matters. It is both orthodox and explosive at the same time.

How so? The originating judicial act cannot be identified without manual inspection of individual case files. No standardised anchor object for future imprisonment is articulated at system level. No form, warrant class, or court identity is disclosed as the termination object grounding detention.

Authority is therefore asserted at a classificatory level — but not demonstrated at architectural level. In the context of jailing people, an inability to demonstrate the court and act explicitly is constitutionally serious.

3. Segmentation functions as a load governor

Where questions become difficult, the system resolves them through segmentation:

“Not held by MoJ.”

“Held in the custody of the court.”

“Judicial College is independent.”

Each of these statements may be formally correct. But together they distribute responsibility across organisational boundaries in ways that frustrate proof-level audit.

Institutional independence is constitutionally important. But when segmentation prevents traceability, it also functions as a structural load governor.

The result is not secrecy. It is diffusion of accountability via architectural fragmentation. This mitigates the immediate visibility of the attribution gap and allows the system to continue operating without systemic redesign.

4. The cost defence looks different in an AI era

Repeatedly, the system relies on manual inspection constraints and FOIA cost boundaries.

In a paper-based system, that would be unsurprising.

But in a process-native justice system operating at national scale — and in an era where classification, linkage, and retrieval costs have collapsed — the inability to produce joins looks less like inevitability and more like architecture.

If automation is sufficient to convict at scale, it must also be sufficient to demonstrate provenance at scale.

Otherwise the enforcement pipeline is asymmetrical: efficient in imposing outcomes, inefficient in demonstrating anchors. In the long run, such asymmetry places strain on democratic accountability.

5. This is not illegality. It is degraded attribution.

Nothing in this FOIA response proves unlawful detention. That is not the claim, and it is a crucial benefit of separating truth from attribution to prevent overreach.

The claim is narrower and more structural.

Custody under this pipeline cannot presently be audited at proof-level attribution across the system as a whole. Authority is said to exist, and may in fact exist in every individual case. But the system does not maintain a publicly demonstrable termination object linking SJP origin, enforcement action, and liberty deprivation at scale.

It is neither “proof” nor “vibes.” It is attribution by institutional implication. That is a problem in protection-of-liberty terms.

6. Why this matters beyond the SJP

The Single Justice Procedure is a test case in a broader ecosystem of automation of administration and enforcement.

The wider issue is process-native governance: systems where adjudication, enforcement, and administrative automation operate in tightly coupled pipelines.

Where such systems scale, attribution must scale with them.

Where provenance does not scale, liberty safeguards migrate from traceability to trust. Trust, however well intentioned, is not a constitutional anchor.

This FOIA response shows that something fundamental is missing — clear public audibility that underpins trust.

What next?

This article is not a polemic. It is a report on an audit in progress. The FOIA response is therefore not the end of the matter, but a waypoint in a continuing examination of provenance and authority.

First, a follow-on request has been made for the three guidance documents referenced in the response (“Calculating Terms in Default,” “Partial Commitment,” and the “Fine Days in Default Calculator”), which were not supplied in accessible form. That request has been acknowledged under reference 260202086, with a statutory response deadline of 2 March 2026.

Second, I intend to seek an internal review in relation to Question 3 — specifically, the refusal to identify the document or record treated operationally as the originating judicial act grounding committal to custody.

Question 3 did not request inspection of individual case files. It sought clarification of what class of document or decision is treated, as a matter of operational practice, as the anchor for detention. The response appears to have interpreted this as a request for case-specific retrieval, rather than a request for description of system-level practice.

Internal review is a normal part of the FOIA framework. The purpose here is not to contest judicial independence or individual case validity, but to clarify whether the system maintains and can articulate a standard document class (i.e. an attribution termination object) grounding deprivation of liberty. That ought not to be a controversial design goal.

If enforcement operates at scale, attribution must also be capable of articulation at scale.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ou6ZmTs_jbY&t=293s