"People think I don't care, but I do"

A candid moment as a Member of Parliament leaps the injustice "astonishment gap"

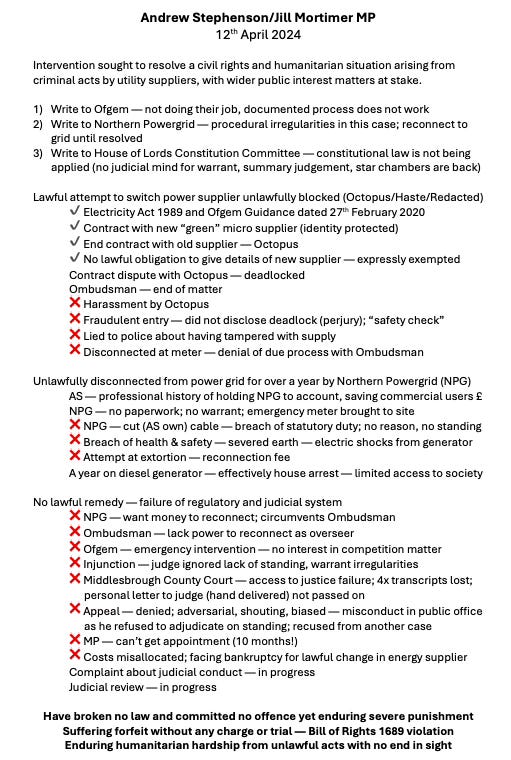

I have just got back home from one of the most intense, interesting, and possibly productive meetings I have ever had. It echoes my good experience at the High Court recently, where there are ultimately honourable and honest people working in an imperfect system as best they can. In this case, the meeting I joined was between my friend Andrew Stephenson, and his parliamentary representative, Jill Mortimer MP. Long-time readers will have read of Mr Stephenson’s epic legal struggle to get reconnected to the power grid after being exiled from normal energised society.

The article headline is a moment of pathos that struck me as important and memorable. Mr Stephenson’s tale of injustice is literally incredible — being hard to believe, yet absolutely factual. Mrs Mortimer is a trained lawyer who clearly can master these situations quickly, with a strong intuitive sense of what is realistic in our world. There was a disconnect between her inner guidance (this was a legal matter she couldn’t resolve) and her outer senses (two polite and credible gentlemen firmly insisting there was a bigger problem that demanded her attention).

The turning point in the meeting was a moment when Mr Stephenson told Mrs Mortimer about one of the first official visits to his property, on the pretext of a “safety check”. The agents of the utility company had lied to police about him having a gas supply (as well as electricity) — which he does not. This is an absolute kind of wrong, and clearly nothing to do with a billing dispute, indicating malice. Having probed Mr Stephenson’s case with a pointed skepticism, I sensed she felt a moment of contrition at having given a victim of a miscarriage of justice a vigorous inquisition.

She explained how the case seemed fantastical, and we agreed! How can so many things go so wrong, and the systems that are meant to protect the public and remedy errors fail to operate? In that tiny moment, she spoke from her heart, and it was no longer Jill Mortimer MP in front of us, but Jill the woman who was doing what she could to help the public from a difficult role. These public surgeries are almost like the legal and social garbage collection, and are not a glamorous occupation. She wasn’t looking for plaudits for candour; the barrister’s cooler professional exterior momentarily dissolved, and the warmer person shone through. Behind the official facade, she is a real person, and just like you and me.

While the initial commercial dispute was to do with billing and changing suppliers, the more serious matter was the grid operator physically disconnecting Mr Stephenson from the main supply by cutting his cable. They had no reason or legal standing to do so, as a kind of extra-judicial punishment. This is not meant to happen in our society — as we typically go to great lengths to ensure the safety of the public and their access to essential services like power and emergency services. You are not meant to find yourself perpetually in the dark and unable to get a new supplier, or get electric shocks from an emergency generator as they severed your earth cable.

Mr Stephenson found an obscure piece of regulatory procedure that meant he could avoid the massive mark-ups of these billing intermediaries, and Octopus (as billing agent) acted like a mafia outfit to shut him down. It is as if Northern Powergrid then undertook “energy assassination” as a warning to others not to try to escape from the utility billing protection racket. The litany of failures looks like a conspiracy theorist has been taking magic mushrooms and given a keyboard and asked to type away, but it is all true. Everything today came down to whether Mr Stephenson’s MP has a conscience that demanded she pay attention to the facts — and she clearly did.

As someone who has been active at both the “penthouse level” of British society, as well as in its “basement”, I can see how difficult it can be for those in authority to empathise with the reality of systemic failure when they do not experience it personally. Not to be critical, but merely to illustrate the point, Mrs Mortimer scoffed a little when I said it was hard for my friend to fight a legal case while constantly on emergency power. It is not only about the continuity of supply to his lights, PC, and printer! It is a nonstop psychological battle to keep pursuing justice, in the face of generator mechanical problems, diesel fuel spills, even a fire.

As Mr Stephenson put it to me, it is like in the film Rambo 2, where he is tied up, has a bag over his head, and there is a rat in it — not once, but every single day. I have had a more minor encounter with Durham County Council, who engage in gangsterism with respect to council tax debt, and wilfully ignore the law and due process. It affects your mental health when those we trust turn upon us, and act out of spite for monetary gain. Once a few injustices happen in a row, it is as if an “astonishment gap” opens up, and onlookers can no longer believe what they are seeing. The dissonance is too great between our inner narrative of the functioning rule of law, and what is presented in front of us.

What is hard for lawmakers to grasp is just how far we have strayed outside of the formal boundaries of our constitution, and the protections it is meant to offer. Industrialised administrative processes, under the rubric of justice but lacking its substance, have automated fraud, extortion, and perjury. In particular, warrants are issued without any judicial mind being applied, and none of the relevant circumstantial data being considered. In this instance, the original contract dispute was deadlocked and awaited resolution by the Ombudsman; nobody had standing to come and disconnect Mr Stephenson, let alone hack up his supply cable.

This meeting was contentious at first, yet respectful throughout, and Mrs Mortimer shook both our hands through the gap in the protective glass in her meeting room on departure. While it was not an easy encounter — I was buzzed afterwards like when doing a conference keynote at maximum energetic output — it was a highly productive one. We had come properly prepared, and she applied her integrity, so the outcome was a win for everyone. As with the High Court, there are good experiences to be had if we let people in authority do their job, and don’t assume the worst of them.

As the first time I have ever met an MP “in the flesh” this was an unforgettable experience, and in a good way. It might not look like our representatives care, but don’t be astonished when some do.

I wonder whether the gravity of the Covid scam has shaken the public sufficiently, that even politicians and bureaucrats are beginning to see the problems, that they themselves don't experience. If so, it's a wonderful time for humanity.

Many people are at the same point Martin, and you summit up perfectly:

“when those we trust turn upon us, and act out of spite for monetary gain. Once a few injustices happen in a row, it is as if an “astonishment gap” opens up, and onlookers can no longer believe what they are seeing. The dissonance is too great between our inner narrative of the functioning rule of law, and what is presented in front of us.

What is hard for lawmakers to grasp is just how far we have strayed outside of the formal boundaries of our constitution, and the protections it is meant to offer. Industrialised administrative processes, under the rubric of justice but lacking its substance, have automated fraud, extortion, and perjury. In particular, warrants are issued without any judicial mind being applied, and none of the relevant circumstantial data being considered.”

I would however have changed “those we trust” to “those that are paid to serve us” to emphasise the Looking Glass we now inhabit.

Has it always been this way or has the great scam just woken us all from our collective slumber ?🤔