Polaris Project on QAnon: attribution "termination propaganda" and the limits of inquiry

How even good-faith institutional responses to human trafficking can suppress truth by prematurely foreclosing authority

I would like to offer an analysis of a 2021 report by the Polaris Project, a charity opposed to human trafficking. The report was produced following claimed harassment directed at Polaris by individuals allegedly associated with “QAnon”, including accusations that the organisation was aiding politically connected entities—such as the Clinton Foundation—in covering up criminal activity.

From truth to termination

My aim here is not to adjudicate the truth or falsity of those accusations. Rather, it is to reframe the episode analytically. In doing so, I draw a clear distinction between

the truth of an inquiry (what might ultimately be established at its end), and

the conditions of its termination (why, how, and where inquiry is brought to a close).

Even if such claims are properly described as “conspiracy theories”, no bad faith is required to explain how the report functions to suppress further inquiry into powerful political actors. The dynamics of attribution alone are sufficient to account for the outcome.

Why intent is not the question

This distinction—between normative debate over what is true and descriptive analysis of when inquiry into truth is allowed to terminate—is crucial. Making it explicit removes much of the heat from highly contested subjects and helps explain how even well-intentioned individuals and institutions can participate in the premature foreclosure of inquiry, to the extent they may even unwittingly act against their remit.

Once this deeper dynamic is brought into view, reconciliation becomes more possible, because we no longer need to denounce motives or intentions, but only to understand how systems behave under strain.

The legal origin of the framework

To see how the road to hell is paved with good intentions, it helps to step back a moment and recap the genesis of the ideas I am presenting on attribution and inquiry into truth.

My work over the last few months on so-called “ghost courts” in the UK has unexpectedly spun off an analytical framework with far wider application. In analysing a court, it is useful to distinguish three layers:

constitution (does the court exist as a matter of law?),

seisin (is the court properly seized of the matter, such that authority is treated as attaching to it?), and

jurisdiction (can that authority be lawfully exercised over the particular subject matter and parties?).

Constitution is largely an objective question of legal fact: one can point to the statutory or constitutional instrument that brings a court into existence. Jurisdiction, by contrast, is a complex mixed question of law and fact, heavily shaped by statute and case law, with numerous edge cases and discretionary doctrines.

Between these sits seisin — the moment at which authority is treated as having attached to an entity in respect of a particular matter. Conceptually, this is where formal legal existence is linked to practical power, connecting objective legal structures with subjective recognition and action.

Three domains: cosmic, ecological, and ludic

What makes this structure interesting and portable is that it links three distinct domains in a pattern that extends well beyond law.

Constitution (the cosmic/ontological domain)

This is the domain of formal existence: what entities, offices, or systems exist at all as a matter of recognised order. It is largely objective and documentary. Either a constituting instrument exists, or it does not. Constitution defines the cosmos— the set of entities to which truth, authority, and liability can, in principle, attach.

Jurisdiction (the ecological/epistemic domain)

This is the domain of contested claims, boundaries, and limits. Here, questions of truth, fairness, authority, and power are argued over, interpreted, and applied in context. Jurisdiction operates within a complex environment of competing interests and uncertainty, much like an ecology, in which different actors struggle over where authority should extend and where it should stop.

Seisin (the ludic/practical domain)

This is the bridging domain that turns ecological contest into actionable and terminable outcomes within the constitutional cosmos. Seisin describes when and how authority is treated as having attached to a particular forum or actor in respect of a particular matter. It is the game: a non-normative account of who is entitled to act, decide, allocate responsibility, and ultimately bring inquiry to an end.

Attribution as the game layer

At this point it becomes clear that attribution itself is the “game”: the mechanism by which contested claims in the ecological domain are translated into authority, responsibility, and outcomes within the constitutional cosmos. The “aha!” is that, across all domains where truth is costly and decisions must be made under uncertainty, attribution reliably degrades through a predictable cascade. It moves from

formal attribution (“Senator Smith stated under oath to Congress…”), to

procedural flow (“the matter was handled in accordance with established process…”), to

rhetorical laundering (“the real issue is the spread of harmful narratives…”), and finally to

institutional override (“authoritative bodies have determined this question is settled or out of bounds”).

These, in turn, define four distinct “truth regimes”, each with different criteria for when inquiry into truth is required to terminate. Much academic, media, and NGO analysis focuses on normative adjudication within these regimes—debating the merits of jurisdictional outcomes and allocating praise or condemnation to constitutional actors. By contrast, the intervening “game” by which contested ecological claims are attributed to formal actors is usually left implicit, under-theorised, and unglamorous.

It is precisely this attributional game space that I seek to extract and examine as a distinct—if unfamiliar—object of analysis. The discomfort this produces is not an error, but a signal: it reflects the strangeness of making explicit a mechanism that ordinarily operates below the level of conscious attention.

Situating the Polaris Project

Before turning to the 2021 report itself, it is worth situating the Polaris Project as an institution. While details of its founding history and funding are not prominently foregrounded on its website, Polaris presents itself as a mature and well-established anti-trafficking organisation. Nothing in its public materials gives me pause or raises concerns about its stated mission or operational integrity.

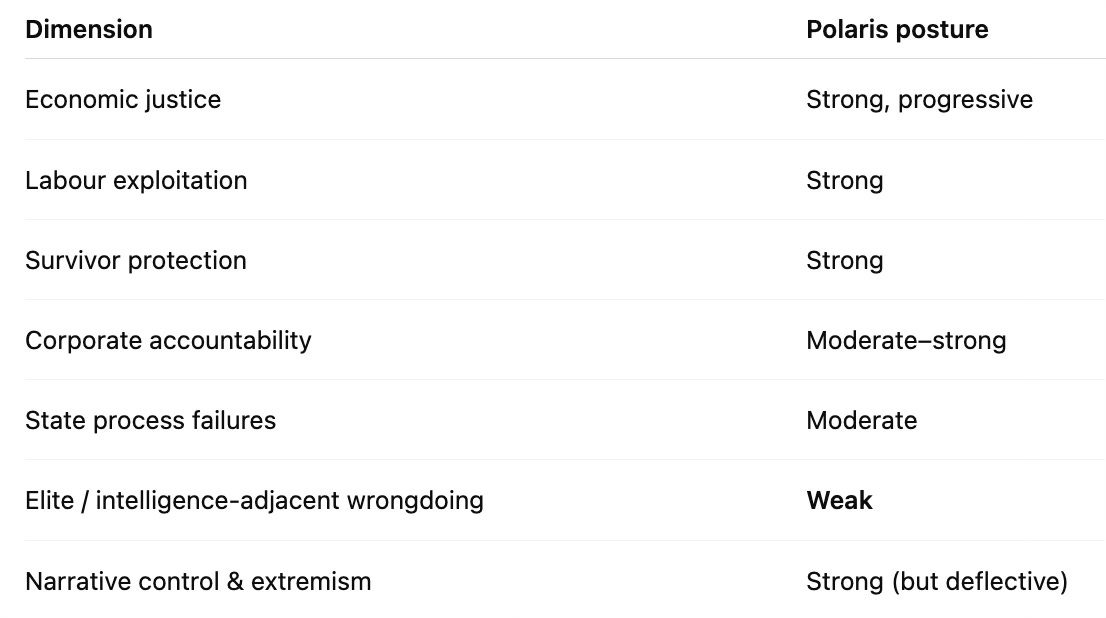

Polaris’s policy orientation is clearly progressive, aligning with contemporary centre-left approaches to labour protection, survivor support, and regulatory reform. That orientation is neither unusual nor problematic in itself, and it is broadly consistent with the NGO ecosystem in which Polaris operates. A review of its research and advocacy initiatives suggests that its work can be characterised, in general terms, as follows:

Progressive norms and the disinformation frame

The report itself is titled Countering QAnon, with the subtitle Understanding the Role of Human Trafficking in the Disinformation–Extremist Nexus. As I have discussed elsewhere, this framing treats “QAnon” as a coherent, unified object, rather than engaging directly with the underlying corpus of Q drops and the specific information claims they contain. In doing so, the report aligns with a broader media and academic convention that abstracts “QAnon” into a single phenomenon, distinct from its internal heterogeneity.

Polaris is operating within that established information landscape, and within prevailing progressive norms of discourse around extremism, disinformation, and harm reduction. That positioning is neither unusual nor suspect. I can readily identify many former colleagues and associates who would hold similar views on disinformation and political extremism while also strongly condemning human trafficking. There is nothing inherently noteworthy about such a stance in itself.

The report is overtly anchored in a contemporary geopolitical frame. It reinforces a set of established narratives concerning the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the events at the Capitol on 6 January 2021, “Pizzagate”, antisemitism, online platforms such as 4chan and Reddit, the Wayfair controversy, Donald Trump, allegations of satanic abuse, the Clinton family, and FBI responses to what are characterised as forms of “extremism”.

This is not the place to adjudicate those matters. It is sufficient to note that these framings are widely accepted within a progressive political and media milieu, and Polaris’s positioning in this regard is neither unusual nor remarkable. Indeed, the deliberate refusal to resolve questions of truth, and the decision instead to focus on when and how inquiry is brought to an end, goes to the heart of the present analysis.

In concentrating our attention on which belief ecology ought to prevail, or which actors deserve recognition within the constitutional order, we often skip a more basic question: how attribution itself determines outcomes. It is this intervening mechanism—rather than the substantive merits of any particular belief—that proves decisive.

Method: separating truth from terminability

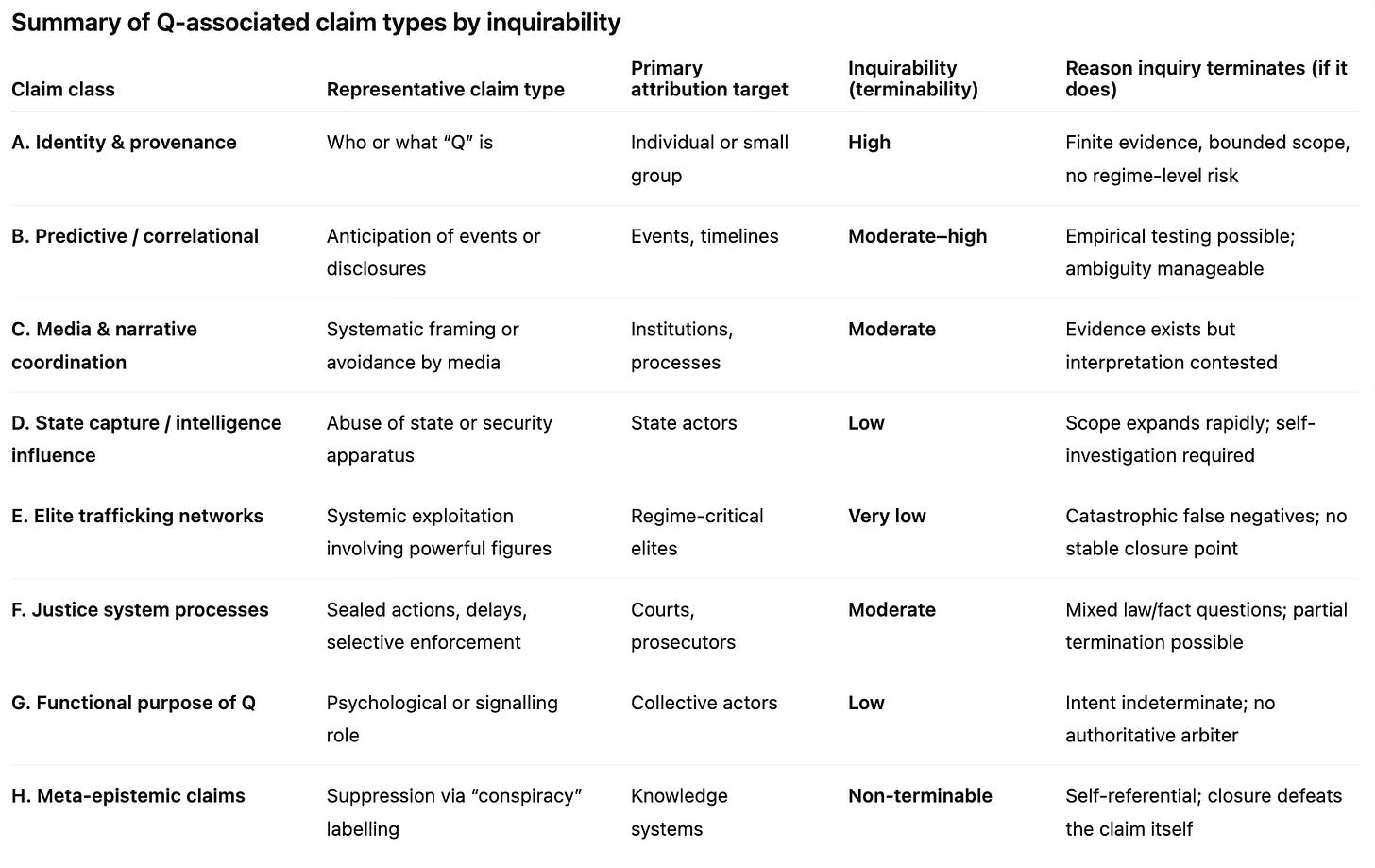

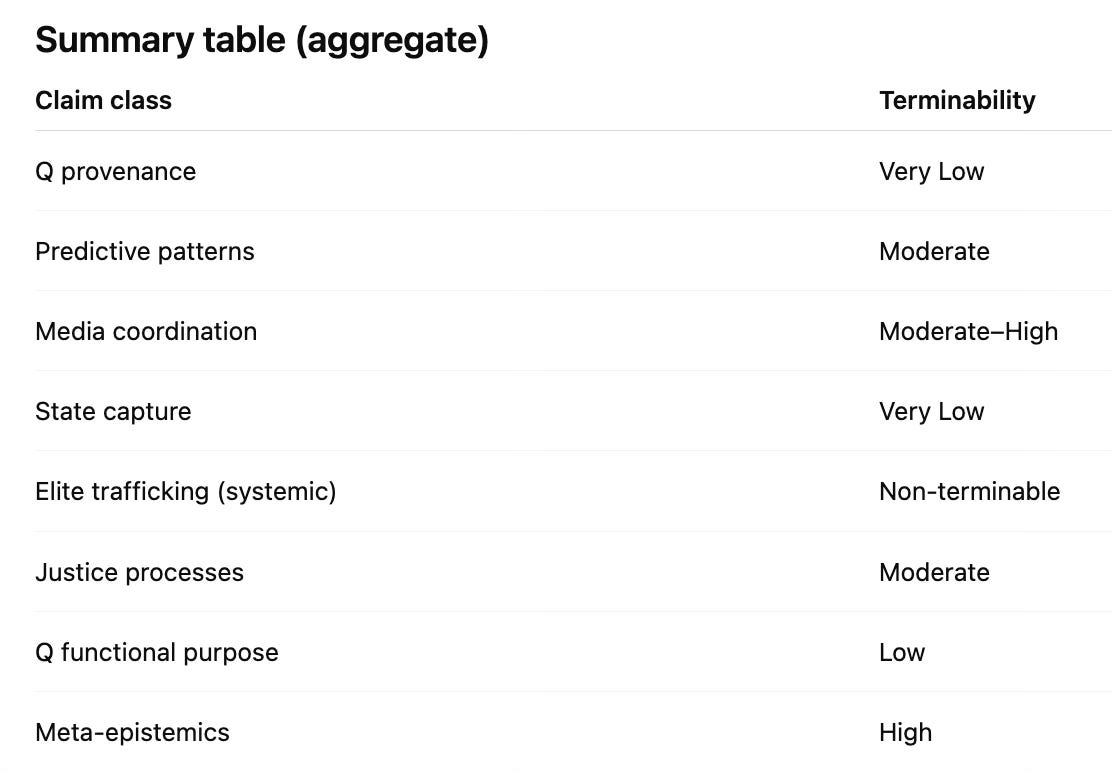

To understand how the termination of inquiry can come to dominate the search for truth, it is helpful to establish a baseline of the truth claims to which the report is reacting. For this purpose, I used my On Q essays as a proxy for the underlying Q drops themselves, and asked an AI system to extract the principal claims, group them thematically, and evaluate each according to how inquirable it is—that is, how readily a claim could be resolved and an investigation into its validity brought to a determinate close.

This is the crux of the analysis. It requires separating two questions that are often conflated:

the substantive truth an inquiry might reach at its end, and

the conditions under which that inquiry can be terminated within finite time and institutional constraints.

The focus here is deliberately on the latter, which is a question of attribution and choice of truth regime.

The move is loosely analogous to Alan Turing’s reasoning about the halting problem in computer science. Turing shifted attention away from what a program computes and toward whether it can be guaranteed to produce an output at all. In a similar spirit, the analysis here brackets the ultimate truth of contested claims and instead examines whether inquiries into them admit of stable, determinate termination—or whether they remain structurally indeterminate.

Mapping the Q claim-space by “inquirability”

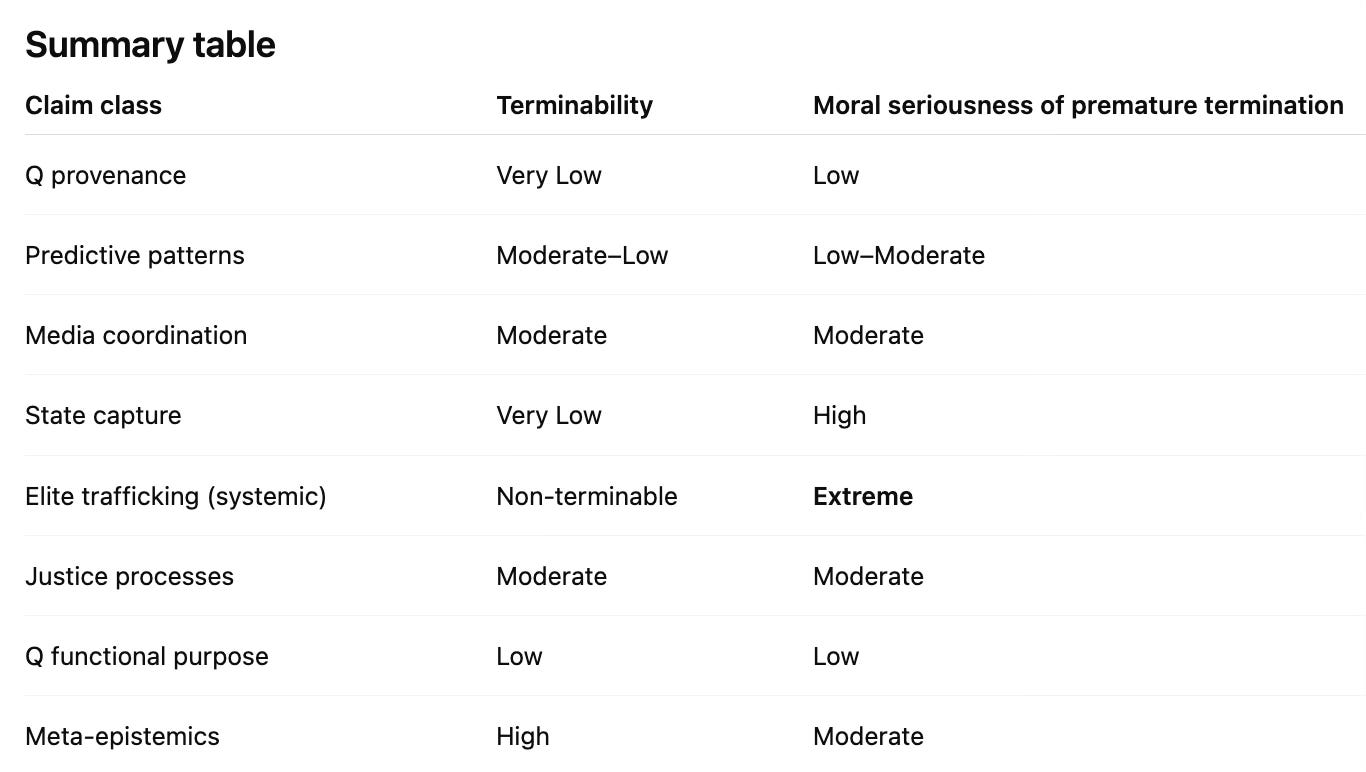

The full details are too heavy for an introductory essay like this, so here is a summary of the categories in which those claims fall:

The key observation is that terminability, not truth, varies systematically across claim types. Claims that point to bounded actors (such as courts or agencies) or finite evidence (such as arrests or documented decisions) admit of stable closure. Claims that escalate attribution toward regime-critical institutions or politically central elites do not, because each line of inquiry opens new questions faster than they can be resolved.

As responsibility is pushed higher up the chain, inquiries lose any natural end point, and institutions move down the familiar ladder of closure—from formal investigation, to procedural handling, to rhetorical reframing, and finally to ruling the question itself out of bounds.

This is the epistemic landscape Polaris was operating in: a political obligation to respond to “QAnon”, coupled with the practical impossibility of resolving the underlying claims through ordinary investigative or procedural means, leaving reframing or boundary-setting as the only workable ways to bring the matter to a close.

Worked examples of inquirability of Q claims

To make the argument concrete, I will examine three representative Q-related claims. They are not selected because of their intrinsic importance, but because they occupy distinct positions in the truth–termination space that the Polaris report is reacting to. Each illustrates a different relationship between inquiry, attribution, and the ability of institutions to bring questions to a close.

1. Predictive claims: easy to test, closed anyway

Certain Q posts appeared to anticipate specific political events or disclosures before they became public.

Illustrative example.

An anonymous online account posted, weeks in advance, that a senior public official would step down “for health reasons” after an internal review. The resignation later occurred, publicly attributed to exactly that cause.

This type of claim is structurally easy to investigate (i.e. fully inquirable). The material is finite and timestamped, the events are observable, and alternative explanations—coincidence, informed guesswork, selective attention, or retrofitting—can be assessed. Inquiry can end with a determinate outcome without requiring attribution to powerful institutions or actors, and without threatening institutional legitimacy.

Termination.

Here, inquiry can conclude through ordinary evidentiary means. Even an inconclusive assessment still counts as closure, because the scope of the claim is bounded and the attribution load is low.

Why this matters.

What is striking is that claims of this kind are rarely examined on their own terms. Their relative safety does not lead to engagement; instead, they are absorbed into a broader refusal to inquire at all. This suggests that termination pressure is not driven solely by feasibility or evidentiary difficulty, but by concern that engaging with any part of the claim space risks legitimising the wider belief ecology.

2. Media claims: examined just enough to stop

Mainstream media and public institutions tend to frame Q-related material in ways that avoid engaging with its internal content, instead treating it as a unified disinformation phenomenon.

Illustrative example.

A national broadcaster adopts an internal guideline instructing staff not to quote or analyse primary-source material from a controversial online movement, instead relying on expert summaries or security briefings.

This is not a claim about hidden crimes or secret coordination, but about observable patterns of framing and omission across actors. It is partially inquirable: media outputs can be analysed, editorial standards compared, and framing choices documented.

Termination.

Inquiry here typically ends procedurally rather than evidentially. Responsibility diffuses across organisations, intent remains contestable, and plausible justifications multiply. Closure is achieved not by resolving whether the proposed claim framing is accurate or distorting, but by appealing to accepted norms such as editorial discretion, harm reduction, or responsible coverage.

Why this matters.

This middle category shows how attention shifts from truth to process. Once the question becomes whether procedures were followed appropriately, not what is finally true, attribution settles quietly. Inquiry terminates, but it does so in a way that feels legitimate precisely because it rests on jurisdictional reasoning (which trusted brand acted) rather than factual resolution (on what lawful basis).

3. Elite claims: reframed to end inquiry

Systemic wrongdoing exists at elite levels of political or economic power, and some Q-related narratives point toward it.

Illustrative example.

A diffuse set of documents, testimonies, and financial records suggests the possibility of serious misconduct within a tightly interconnected political and economic network, without any single piece of evidence sufficient to force a definitive conclusion.

Whatever one thinks of such claims substantively, they are structurally non-terminable and non-inquirable. Attribution escalates toward regime-critical institutions or highly centralised elites, often operating under conditions of classification or secrecy. Evidence invites further inquiry rather than closure, false negatives carry severe moral weight, and any investigation sufficient to resolve the claim would require the system to investigate itself.

Termination.

Absent declassification or formal disclosure, there is no stable endpoint at which inquiry can conclude through resolution. Closure can only be achieved by other means: reframing the issue as disinformation, discouraging further attention, or declaring the question itself out of bounds.

Why this matters.

This is the pressure point that most directly illuminates the Polaris report. No assumption about the truth or falsity of the claim is required to explain the response. Its non-terminability alone is sufficient. Faced with claims that cannot be safely closed, institutions prioritise ending inquiry itself (via the attribution cascade).

What these examples show

Taken together, these three cases show that the decisive variable is not truth, but terminability. Some claims could be investigated and closed without destabilising effects, yet are not. Others can be examined only up to the point where procedural justification takes over. Still others force termination by necessity, because no authoritative endpoint exists.

Seen this way, the Polaris report is responding less to the content of Q-related claims than to their position in the truth–termination space. Once attribution threatens to climb beyond what institutions can safely bear, the search for truth gives way to the imperative to bring inquiry to an end. That dynamic—rather than bad faith or factual adjudication—is what this analysis seeks to make visible.

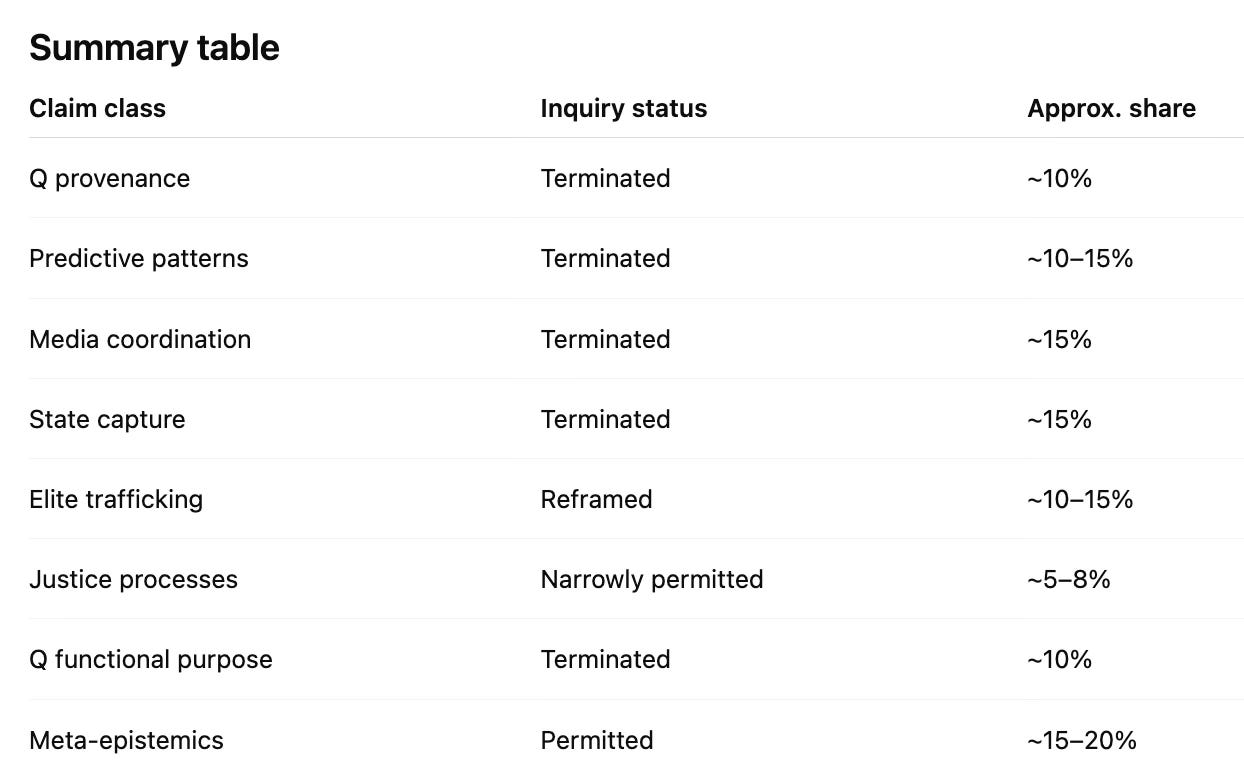

How the Polaris report allocates inquiry

The Polaris report does not respond to “QAnon” as a single, undifferentiated phenomenon, but to two related claim-spaces:

a primary space defined by the Q drops themselves, and

a secondary space constituted by the public interpretations and reactions those drops generate. This includes “attacks” on the Polaris Project by those nominally aligned to the Q drops.

For the purposes of this analysis, I restrict attention to the former.

The key question, then, is not whether the Q claims are true or false, but how the Polaris report treats inquiry into them. To what extent does it allow investigation to proceed through formal or procedural means that could bring inquiry to a legitimate close, and to what extent does it instead terminate inquiry prematurely—by assigning a settled “truth” through rhetorical reframing or by declaring the questions themselves out of bounds?

My analysis suggests the following pattern.

Q-themed claims terminated at the threshold

First, the report functions to terminate inquiry into roughly 65–75% of the underlying claim space. These are predominantly claims that attribute coordination or responsibility upward—toward elite actors, intelligence provenance, media coordination, or trafficking networks. Rather than being examined individually, they are effectively collapsed into a single category of “extremist narrative”, bringing inquiry to a close without formal or procedural investigation.

Inquiry permitted where attribution remains low

Second, the report permits sustained inquiry into approximately 15–20% of claims, primarily those framed in psychological, sociological, or platform-dynamics terms. These claims concern belief formation, online behaviour, radicalisation pathways, and information spread, and can be investigated without requiring attribution to powerful institutions or actors.

Inquiry permitted only after reframing as risk

Finally, the remaining 10–15% of claims are admitted only conditionally. Inquiry is allowed to proceed insofar as these claims are reframed as risk vectors—that is, as factors contributing to harm, instability, or radicalisation—rather than as factual propositions about events, actors, or wrongdoing. In this reframed form, inquiry can continue, but only after the question of truth has been displaced into a preferred “extremist” framing.

Worked examples of Polaris early termination of inquiry

The structural accounting above shows a clear pattern in how the Polaris report treats different classes of Q-derived claims. However, working through every category in detail would obscure rather than clarify the central mechanism. Instead, it is more instructive to examine three representative cases, chosen to mirror the earlier discussion of inquirability:

one claim type that could, in principle, be investigated and closed;

one that is permitted only at the level of procedure and process; and

one that is structurally non-terminable and therefore subject to premature closure.

These examples are not selected for their substantive importance, but because together they illustrate how attribution load, rather than truth, governs where inquiry is allowed to end.

Example 1 — Predictive patterns

Claim class: Predictive or foresight behaviour in Q drops.

Result: Terminated despite high inquirability.

“QAnon-peddled disinformation weaves false narratives together in ways that make them appear credible to susceptible audiences.”

“False narratives and conspiracy theories surrounding child sex trafficking serve as a gateway narrative that radicalizes susceptible audiences.”

“Although hate certainly played a role… there was another far more benevolent force that attracted others: a concern — albeit fueled by false narratives and conspiracy theories — for the safety of children.”

Claims that Q material appeared to foreshadow events, align temporally with official actions, or anticipate public disclosures are treated by the report as categorically illegitimate. Pattern recognition itself is framed as a cognitive error: coincidence is assumed, and any attempt to test temporal alignment is characterised as “apophenia”, motivated reasoning, or narrative self-reinforcement. As a result, inquiry is closed at the threshold, before any substantive examination can begin.

What makes this case instructive is that, structurally, it is among the most inquirable claim types. The corpus is finite and timestamped, the referenced events are observable, and competing explanations—chance, informed speculation, insider knowledge, or retrospective fitting—are all amenable to empirical testing. Inquiry could terminate cleanly, whether affirmatively or dismissively, without requiring attribution to powerful institutions or threatening institutional legitimacy.

Yet the report does not permit even this bounded form of investigation. Termination occurs not because inquiry would be difficult or destabilising, but because allowing examination would reopen questions about falsifiability, sequencing, and informational asymmetries that the report treats as categorically unsafe. This illustrates a pre-emptive mode of termination: inquiry is closed not at its end, but before it begins, despite being structurally manageable.

Example 2 — Media coordination

Claim class: Media coordination and agenda-setting.

Result: Procedurally closed.

“Policymakers must forcefully condemn conspiracy theories and disinformation about human trafficking.”

“A coordinated, multi-stakeholder effort is needed to develop and implement strategies to impart the truth about human trafficking.”

“Anti human trafficking organizations must be empowered and supported to speak forcefully and quickly against disinformation.”

Claims that mainstream media organisations act in coordinated or structurally aligned ways—through shared framing, omission, or narrative convergence—are addressed by the report in a more permissive but ultimately limiting manner. Rather than being dismissed outright, such claims are reframed as expressions of institutional distrust, grievance, or susceptibility to radicalising narratives directed against “trusted sources”.

Here, inquiry is partially permitted. Media outputs are public, framing patterns can be documented, and cross-outlet comparison is possible. However, investigation consistently stalls once procedural justifications are introduced. Appeals to journalistic standards, editorial independence, audience safety, or the avoidance of amplification shift the focus away from accuracy and toward propriety.

Termination, in this case, is achieved through jurisdictional reasoning. Once media institutions are positioned as baseline epistemic authorities, critique of their collective behaviour becomes, by definition, suspect. Attribution settles without ever being explicitly decided. Inquiry is allowed to proceed just far enough to justify its own closure, illustrating how procedural legitimacy can substitute for factual resolution.

Example 3 — Elite trafficking networks

Claim class: Elite trafficking and child exploitation.

Result: Non-terminable, reframed.

“QAnon’s central premise is that a global cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles in the Democratic party and Hollywood elite form the core of a transnational sex trafficking ring.”

“Disinformation about human trafficking serves as a gateway narrative that radicalizes susceptible audiences to condone, and even perform, acts of violence and terrorism.”

“Conspiracy theories around trafficking should be treated as a critical threat to national security and the success of civil society organizations.”

“Human trafficking disinformation was, and will continue to be, specifically weaponized as a way to radicalize susceptible populations into violent extremism.”

This is the most revealing case. Unlike many other upward-attributing claims, the report explicitly affirms that human trafficking is real, serious, and deserving of attention. However, any attempt to link trafficking to elite actors, institutional networks, or politically central figures is treated as inherently dangerous and is reframed not as a factual proposition, but as a driver of radicalisation, misinformation, or harm.

The reason is structural. Claims of this kind are non-terminable. Attribution escalates rapidly toward regime-critical institutions, evidence invites further inquiry rather than closure, and false negatives carry severe moral consequences. Any investigation sufficient to resolve the claim would require institutions to investigate themselves, often across jurisdictions and under conditions of classification or secrecy.

As a result, inquiry cannot end through resolution. It can only be ended by reframing. The report’s central move is to permit discussion of trafficking only after the question of elite attribution has been displaced, transforming the issue from one of truth into one of risk management. This is the clearest instance in the analysis where termination fully replaces inquiry.

What these examples show

Across these three cases, the pattern identified in the aggregate accounting becomes concrete:

claims that could be investigated safely are terminated early;

claims that threaten epistemic authority are closed procedurally; and

claims that are structurally non-terminable are reframed so that inquiry into truth is no longer admissible.

Seen this way, the Polaris report is not primarily adjudicating Q claims. It is managing where inquiry is allowed to end. The distribution shown in the summary table is not accidental; it tracks attribution load almost perfectly.

That is the core of the argument: termination dynamics, not truth evaluation, explain the report’s structure and conclusions.

Moral consequences without moral accusation

The strength of an attribution-first approach—one that separates the ludic from the cosmic and ecological domains—is that it allows claims to be evaluated in a purely descriptive, non-normative way. It asks not whether claims are true or false, sincere or manipulative, consequential or trivial, but how inquiry into them is structured and whether it admits of termination. By bracketing normative judgment at this stage, the analysis avoids importing subjective bias into conclusions drawn within its constrained domain.

That said, normativity does re-enter once the interface is clearly defined. Claims do not arrive morally neutral, even when their truth remains unsettled. The Q drops, in particular, are often laden with moral significance independent of their factual status. When inquiry into such claims is foreclosed prematurely, that foreclosure itself has moral weight. The intention may not be to enable harm or wrongdoing, but the effect can nonetheless be to insulate certain possibilities from scrutiny.

This is the central tension. The very conditions that may make the Polaris Project effective in its day-to-day work—clear epistemic boundaries, strong normative commitments, and an emphasis on harm prevention—may also limit its ability to register or integrate signals that originate outside its prevailing political or epistemic frame. In such cases, termination does not merely resolve uncertainty; it risks suppressing information precisely where the stakes are highest.

Good faith, bad dynamics

It is easy to see how people acting in good faith—though perhaps mistaken about certain geopolitical matters—can experience hostile or indiscriminate accusations as deranged. When extreme claims are made that collapse all progressive-aligned actors into complicity with serious crimes, those claims are readily dismissed as evidence of paranoia or malice. In turn, this reinforces prior prejudices against Trump-, MAGA-, or Q-associated themes, which are then treated as intrinsically irrational or dangerous.

In this dynamic, those making the accusations are themselves operating within a “truth mode” of their own—constructing unfounded theories in which ideological alignment is taken as proof of moral culpability. The result is a self-sealing system of belief on all sides, in which each camp interprets the excesses of the other as confirmation of its worst assumptions. Ironically, this can generate radicalisation without any party intending to deceive, manipulate, or do harm.

Not truth propaganda, but termination

What makes the Polaris Project’s report on QAnon of analytical interest, then, is not the specific claims it makes about Q or its critics. Rather, it is that the outcome it exemplifies can arise entirely as an emergent effect of uncoordinated processes driven by attribution mechanics. Once it becomes unthinkable to assign responsibility to widely trusted political or institutional actors—because doing so would undermine the enterprise’s own foundations—inquiry has to be closed by other means.

On this account, the production of what I have called termination propaganda does not require conspiracy, bad faith, or malign intent. Unlike truth propaganda, which seeks to persuade by asserting or distorting facts, termination propaganda works by ending the conditions under which certain questions can be asked at all. It follows naturally from incentive structures aligned to attribution constraints. Inquiry ends not because truth has been resolved, but because allowing attribution to travel further would destabilise the conditions under which the institution understands itself and its work.