Wikipedia’s synthetic villains and heroes

How the online encyclopaedia constructs narrative governance objects

I recently clicked a link on social media to a YouTube interview between Richard Vobes—something of a twenty-first-century ambassador for Englishness in online video—and Charles Foxtrot, a pseudonymous author discussing his new book Why Nothing Can Stop What Is Coming, which explores the so-called “Q drops”. Beneath the video sat the familiar YouTube disclaimer warning viewers that the content related to “conspiracy theories”. Before a word had been spoken, the material had already been classified.

That disclaimer functions as an ontological anchor. It does not argue against the content; it pre-evaluates it. It tells the viewer what kind of thing this is, and therefore how it should be received, long before any claims are assessed on their merits. This is not accidental, nor is it unique to YouTube. It is a standard technique of framing: assign an object to a narrative class, and its meaning, credibility, and permissible responses are largely decided in advance.

This essay explores how Wikipedia has become adept at constructing synthetic villains and heroes: narrative governance objects that stabilise social meaning under uncertainty while appearing as neutral reference material. “QAnon” is a particularly stark example—an outlier among contemporary bogeymen, though not unique in form or purpose. The same techniques are also used to create institutional “darlings”, the heroic counterparts to these manufactured villains, shaped differently but serving a similar stabilising function.

Goals and methods

This essay is not concerned with adjudicating the truth or falsity of any claims associated with “Q”, nor with defending or condemning any individuals labelled by the term “QAnon”. Its purpose is to examine how institutions respond when something attracts attention and concern, but has no clear author, leader, or defined membership—yet still has to be named and handled for practical reasons.

The analysis applies a neutral ∆∑ attribution framework to Wikipedia’s lead sentences, category choices, and sourcing patterns, comparing them across a wide range of extremist organisations, decentralised movements, moral panics, and abstract ideological labels. AI-assisted tools were used extensively in the analysis and throughout the drafting and editing, with me acting as the orchestrator—setting direction, making judgments, and integrating the final text.

The argument does not depend on how any political or historical disputes are ultimately resolved. It asks what happens to genuine inquiry when institutions treat contested and unresolved phenomena as settled facts in order to keep functioning.

Abstracting Wikipedia through an attribution lens

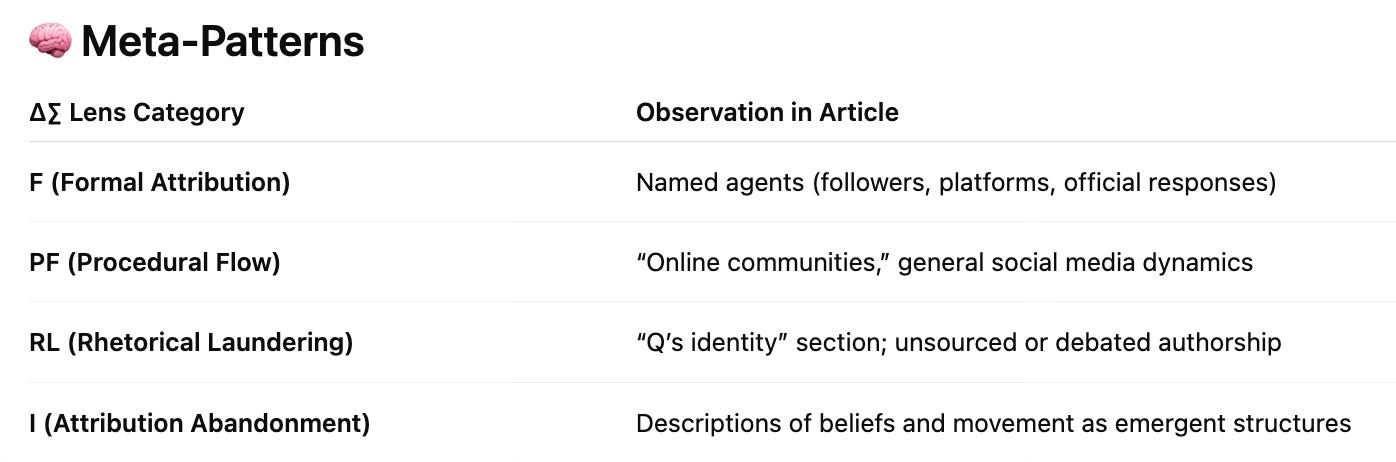

I started by analysing the Wikipedia article on QAnon through the ∆∑ framework, focusing not on what it claims, but on how those claims are constructed. This moves the discussion away from disputed meanings and onto the underlying structure of the article itself.

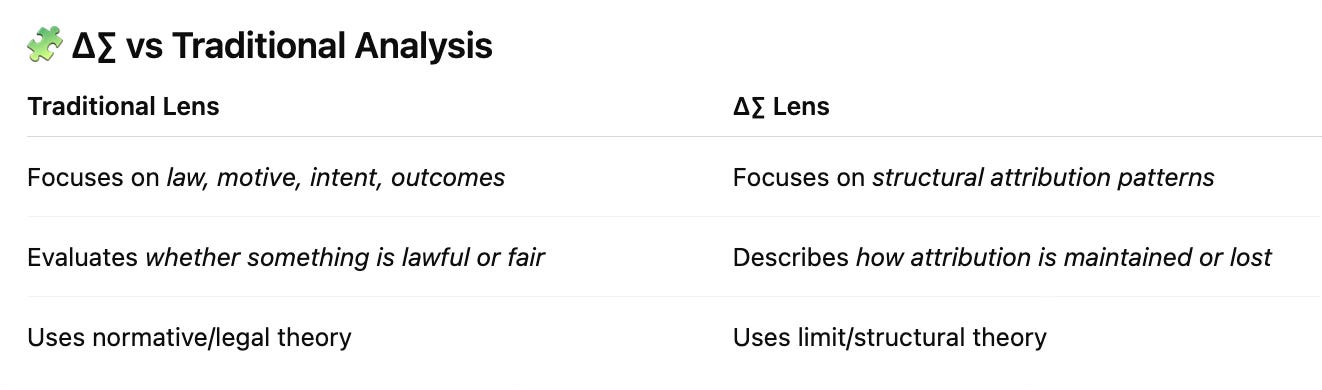

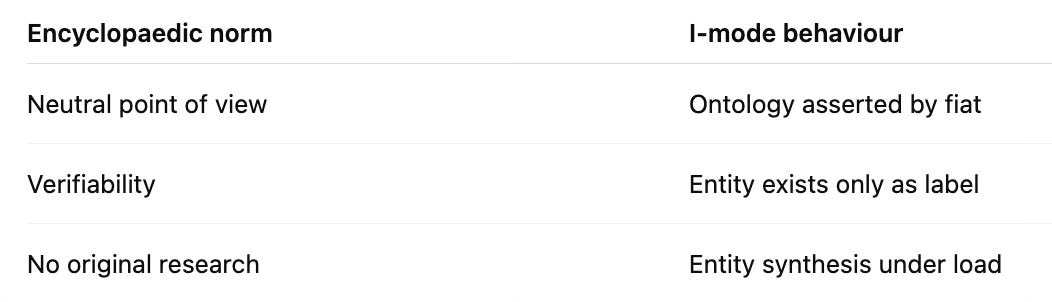

As background, ∆∑ is a framework for classifying how claims are attributed, rather than whether they are true or false. It groups claims into four attribution modes, based on where responsibility and accountability for the claim actually sit.

F (Formal) — The claim is clearly attributed to a named source or authority, with explicit responsibility for its accuracy.

PF (Procedural Flow) — The claim is attributed to an observed process or pattern (“this tends to happen”), without any single person or institution taking formal responsibility for asserting it.

RL (Rhetorical Laundering) — Attribution is softened or obscured through language (“is widely believed”, “has been linked to”), allowing narrative plausibility to stand in for explicit sourcing.

I (Institutional Override) — Attribution is effectively abandoned. The claim is treated as true because institutional continuity or authority requires it to be so, not because responsibility can be traced.

All four modes appear in the article. Importantly, this framework does not judge whether a claim is true or false. It identifies the attribution regime under which the claim is being made. Claims in any of these modes may ultimately turn out to be correct or incorrect—the distinction lies in how responsibility for the claim is handled, not in its factual outcome.

What Wikipedia is doing is constructing a new noun, “QAnon”, around a label already used in the media, but shifting its meaning

from a label (F/PF modes, where we can point to who is using the term in specific articles)

to a movement (RL/I modes, where the label is treated as something that exists in its own right).

That shift gives “QAnon” formal category membership (“far-right conspiracy movement”), which in turn enables downstream governance: media framing, academic study, platform enforcement, political labelling, and security discourse.

Here, the ends (governing belief) justify the means (constructing the villain).

The hodgepodge that makes “QAnon” into a “frankenthing”

This new noun bundles together a disparate set of concepts:

Anonymous imageboard posts (2017–2018)

Authored by an unknown person or persons (“Q”), posted on 4chan, 8chan, and 8kun; no verified identity, authority, or guarantee of continuity.Interpretive communities (“bakers”, decoders)

Thousands of independent interpreters; no coordination, hierarchy, or mandate; interpretations often mutually contradictory.Influencers and content creators

YouTubers, bloggers, Telegram admins, and grifters; often monetised and largely post-Q; frequently add content absent from the original Q drops.Borrowed legacy conspiracy themes or tropes

Pizzagate, Satanic Panic, blood libel archetypes, Deep State narratives; these predate Q and were not authored by Q.Political opportunists and tag-users

Individuals using “QAnon” language for attention, alignment, or provocation; including hostile actors, ironic users, and provocateurs.Followers / believers (as a population)

No membership criteria, doctrine enforcement, or boundary control.Offline incidents attributed “to QAnon”

Actions by individuals with varying degrees of self-identification; often retroactively classified as QAnon-related.Media, academic, NGO, and government framing

Secondary descriptions and categorisations; these frequently define “QAnon” more than the original Q material ever did.

I know someone whose child was taken from her because she was said to be indirectly associated with “QAnon”, described as a “known domestic terrorist entity” (!) — without proof of either claim. Once the above list is examined, such an allegation loses any coherent meaning. This is effectively the weaponisation of lawful political speech and freedom of association. Without the “ontological laundering” performed by entities like Wikipedia, such moves would not be possible. Something cannot be a hero or a villain until it is declared to exist; that is the ontological work Wikipedia is doing, and it is what enables these wrongs.

More formally, Wikipedia is creating a new synthetic attribution substrate: people can cite the QAnon page as authority for “QAnon” being a (bad) thing, even though the page itself does not reference anything with the properties of a coherent entity, but rather an agglomeration of ideas and behaviours. Without that substrate, many secondary claims (“QAnon influenced X”, “QAnon is Y”) become much harder to state cleanly — or collapse into absurdity.

Does “QAnon” qualify as an attributable entity?

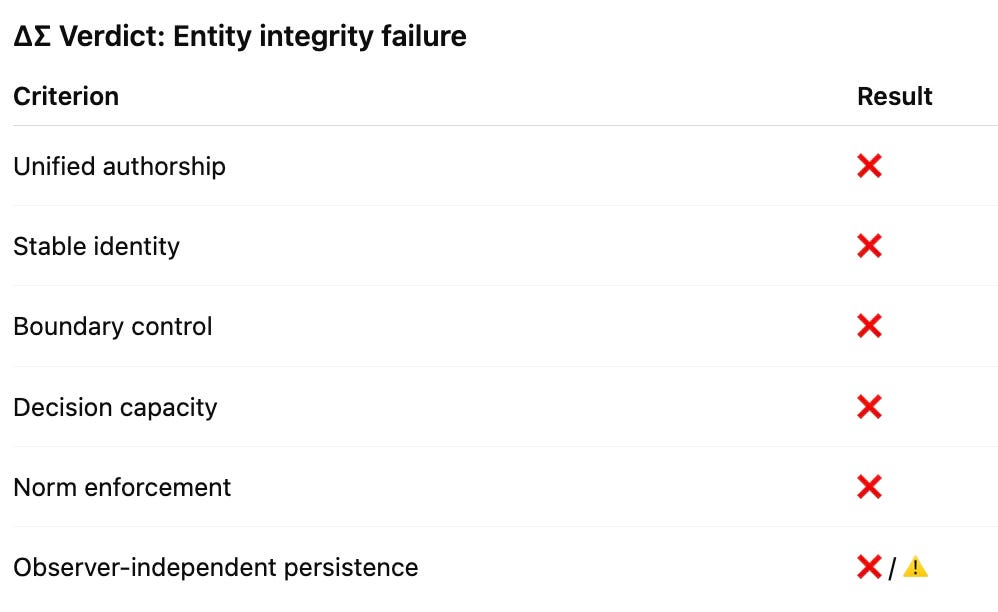

We now evaluate whether the heterogeneous components bundled under the label “QAnon” meet the minimum conditions required for it to function as a single attributable entity—one capable of bearing responsibility, agency, or causal properties.

The detailed exposition is omitted here. In short, “QAnon” lacks the structural integrity required to function as a genuine attributable entity. The label persists as an observer-sustained construct rather than as an internally coherent actor or organisation.

Because direct attribution is impossible, Wikipedia:

Constructs a noun

Stabilises it via category labels

Uses it as a surrogate agent

Routes responsibility through it

This allows statements like:

“QAnon claims…”

“QAnon promotes…”

“QAnon is linked to…”

All of which grammatically require an entity — but none of which rest on a valid attribution chain.

To take one example, the original article begins:

“QAnon is a far-right extremist movement…”

If we remove the presumption that “QAnon” is a thing, and insist on formal attribution, we instead get:

“Since 2017, a collection of anonymous online posts attributed to a figure known as ‘Q’, along with subsequent interpretations and derivative content produced by unaffiliated individuals, has been associated by some researchers and institutions with far-right extremist beliefs held by subsets of participants.”

That is much harder to attach social opprobrium or censorship to!

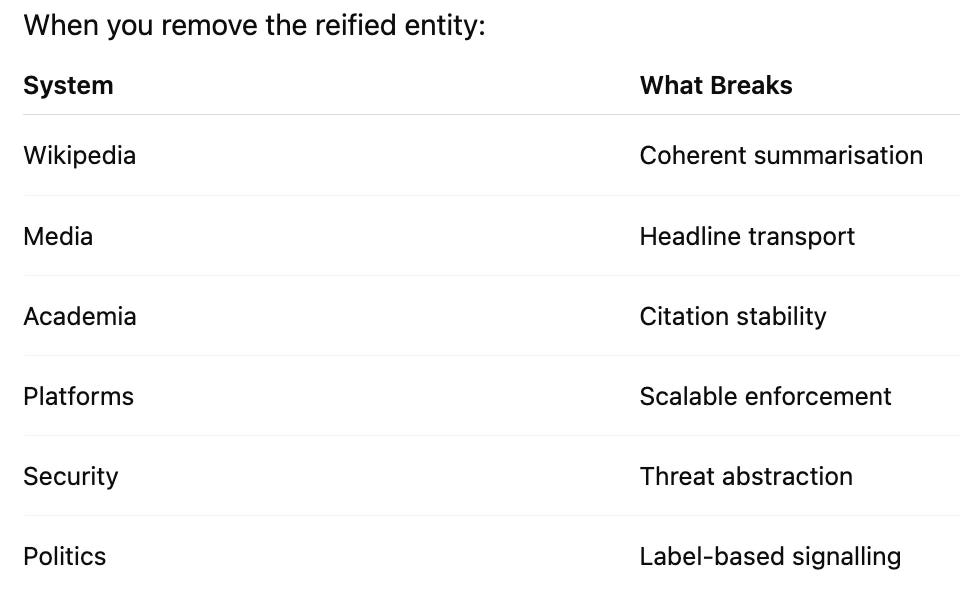

Consequently, absent the ontological laundering by Wikipedia, a whole series of consequences collapse:

Synthetic governance requires synthetic objects onto which real beliefs and behaviours can be attached and acted upon.

Not an entity, not attributable, so what is “QAnon”?

If “QAnon” is not an entity, and is not itself attributable, then it exists because multiple institutions require a single object to which they can attribute meaning in order to function — not because such an object exists naturally.

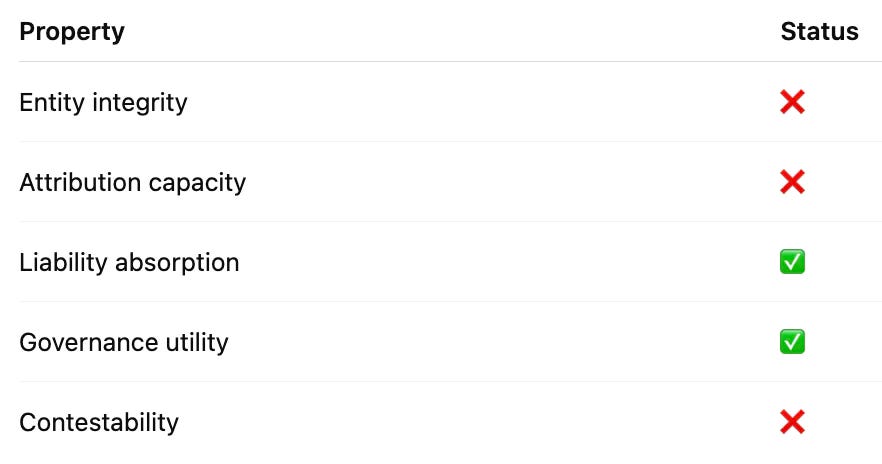

A “liability sink” must satisfy certain properties. “QAnon” satisfies all of them.

No legal standing — It cannot sue, reply, correct, or demand evidence.

No leadership — There is no one to hold accountable instead.

Moral asymmetry — It can be blamed, but not wronged.

Narrative elasticity — Anything adjacent can be folded in (“QAnon-linked”, “QAnon-adjacent”).

Public plausibility — The label already carries moral charge, so additions face little resistance.

“QAnon” is a synthetic governance object. It is not an actor, an organisation, a doctrine, nor a movement in the classical sense. Rather, it is a compressed semantic artefact created to absorb attribution that cannot otherwise be carried.

Remove it, and the entire discourse stack destabilises.

For example, it absorbs media liability. Instead of identifying which outlets amplified which claims, explaining editorial failures, or tracing the incentives behind sensationalism, media can simply say:

“QAnon misinformation spread…”

This displaces liability from editorial decisions onto the object, abstracting responsibility away with maximum absorption and zero back pressure. No government department, PR-aware corporation, trademark owner, or libelled person will fight back directly.

Under normal attribution:

actors → actions → liability

With “QAnon”:

outcomes → anxiety → object → retroactive attribution

The object is not the cause; it is the collector. This is the inversion: liability precedes entity, not the other way around.

This is where things get interesting, because we can now see what “QAnon” actually is, and what it does. The next question is how it does it.

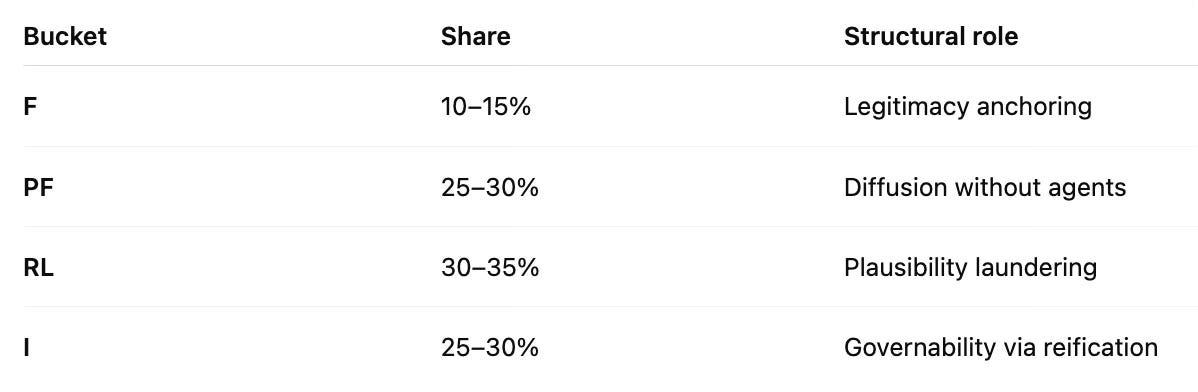

The attribution dynamics of the Wikipedia “QAnon page”

Our first port of call is the QAnon page itself. You would expect an encyclopaedia to be built primarily from attributable information with a formal source (F) or a clear observable pattern (PF). This page is not. Instead, it relies largely on rhetorical laundering (RL) and, ultimately, institutional override (I).

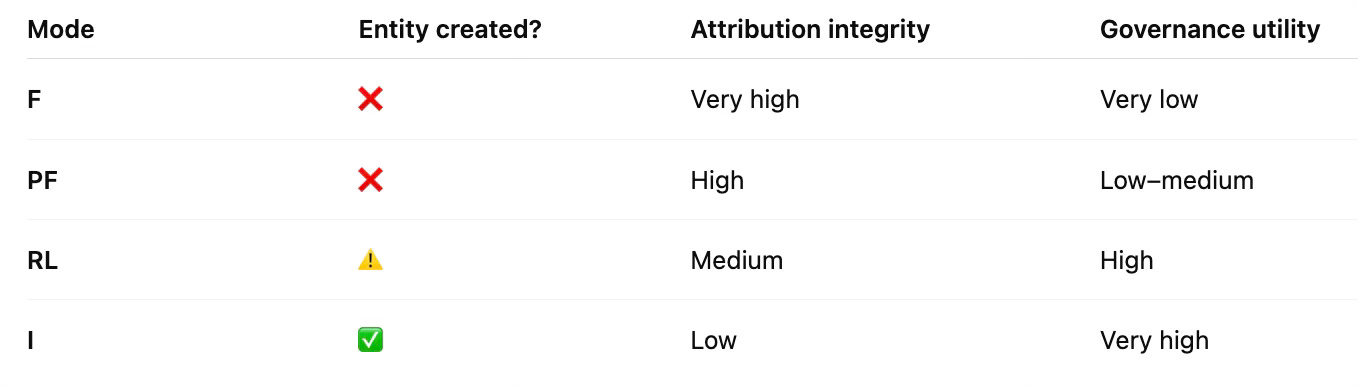

To bring this to life, let’s compare four formulations of the introductory sentence, from most to least formal — we touched on the first and last earlier. The choice of lead sentence is never neutral: it determines what can be said, blamed, or acted upon downstream.

1. F-mode (Formal attribution / highest integrity)

“Between 2017 and 2020, anonymous posts made on internet imageboards by an unidentified author or authors using the pseudonym ‘Q’, together with independently produced derivative content by unaffiliated individuals, were described by various media outlets and organisations as constituting what they labelled ‘QAnon’.”

The F-mode preserves maximum precision by refusing to reify “QAnon” as anything more than a label applied by observers — but at the cost of being cumbersome and nearly ungovernable.

2. PF-mode (Procedural flow / sociological framing)

“QAnon refers to a loosely connected set of narratives, symbols, and online interpretive practices that emerged from anonymous internet posts beginning in 2017 and were subsequently adopted, adapted, and circulated by diverse and unaffiliated online communities.”

The PF-mode treats it as an emergent process rather than an actor, retaining analytical honesty while sacrificing clean causal responsibility.

3. RL-mode (Rhetorical laundering / plausible authority)

“QAnon is a term used to describe a conspiracy theory ecosystem that originated from anonymous online posts in 2017 and has since been associated by researchers, media organisations, and authorities with far-right political narratives and extremist beliefs.”

The RL-mode soft-launders attribution through hedges and borrowed authority, gaining plausibility and classification power without full inspectability.

4. I-mode (Institutional override / current Wikipedia form)

“QAnon is a far-right American political conspiracy theory and movement.”

The I-mode simply asserts a unified entity by institutional fiat, collapsing attribution entirely to achieve maximum governability and rhetorical force — turning “QAnon” into a ready-made liability sink for policy, moderation, and discourse.

In summary

It is the final formulation that matters. Once the purpose of the QAnon page is understood as governance rather than encyclopaedic description, its structure makes sense. It no longer follows the epistemic code of an encyclopaedia.

These are distinct regimes of truth that cannot be reduced to one another.

The QAnon article privileges RL-truth and I-truth as its dominant modes, and that choice is revealing:

Formal systems recognise truth only when attribution is auditable (F-truth), because responsibility and liability must be traceable for the system to function.

Humans under uncertainty act on convergent patterns (PF-truth), because waiting for formal authorisation in risky situations is often impractical or unsafe.

Narratives stabilise meaning when attribution fragments (RL-truth), allowing coordinated decisions to be made even when formal rules or clear sources are unavailable.

Institutions override ontology when continuity is threatened (I-truth), prioritising operational stability over unresolved questions of truth in the moment.

None of these modes is inherently “right” or “wrong”; they are tools for different jobs, aligned with different needs for narrative stabilisation and institutional continuity. Applied to the QAnon Wikipedia article, this is not a matter of interpretation or intent—it follows directly from the article’s attribution dynamics and structure.

Is this weak attribution because QAnon is “so bad”?

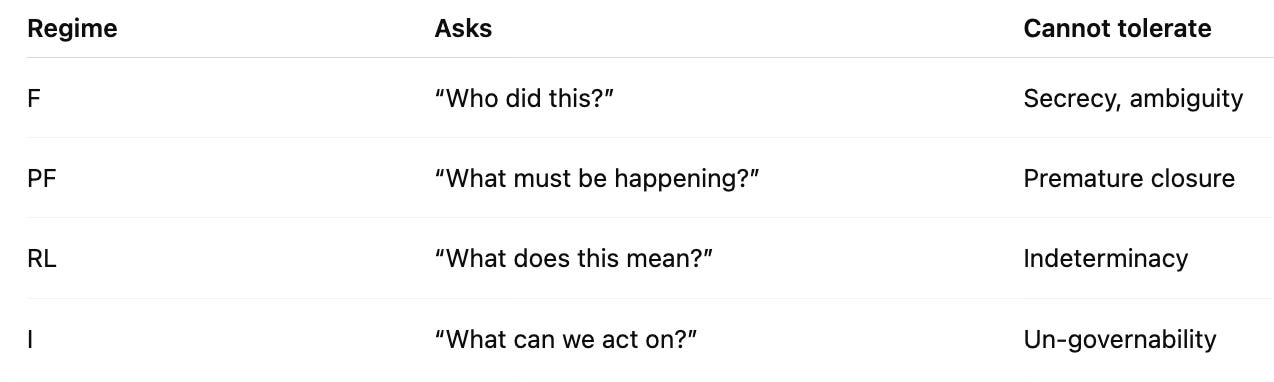

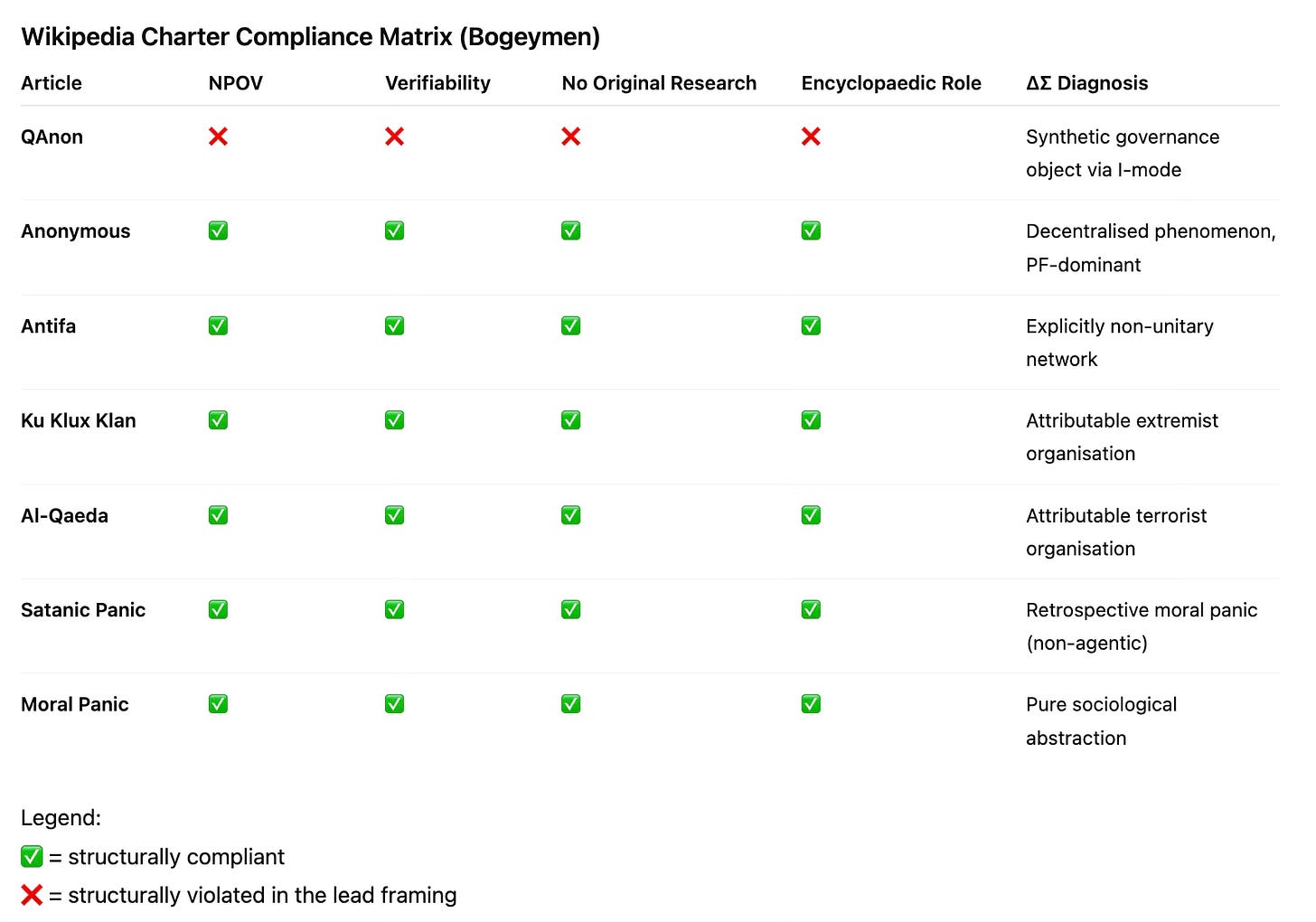

An obvious question is whether this attribution pattern is “special” to QAnon because it is perceived as being “so bad”. To test that, we can compare it with other low-valence or contentious phenomena.

Real entities: Ku Klux Klan, Al-Qaeda

Benign abstractions: Moral Panic, Satanic Panic

Decentralised but contentious phenomena: Anonymous, Antifa

Even if one were to argue that Al-Qaeda is, in some sense, a front or proxy, it is still “real” in the limited but important sense that it has identifiable leadership, continuity, and organisational form. So how does QAnon compare within this group?

The result is striking. Among comparable “bogeyman” articles on Wikipedia, QAnon alone requires sustained Institutional Override to remain a usable object of attribution, classification, and governance. All other cases either possess genuine entity integrity or are explicitly treated as non-agentic phenomena.

If we re-sort the same examples by moral valence—from most to least objectionable, as typically presented by the mass media—the pattern remains unchanged.

QAnon is not treated differently because it is worse, but because it is harder to attribute. Wikipedia resolves that difficulty by substituting Institutional Override where other articles rely on Formal or Procedural attribution. In other words, Wikipedia needed an object to carry liability and govern discourse, and moral valence alone could not supply one.

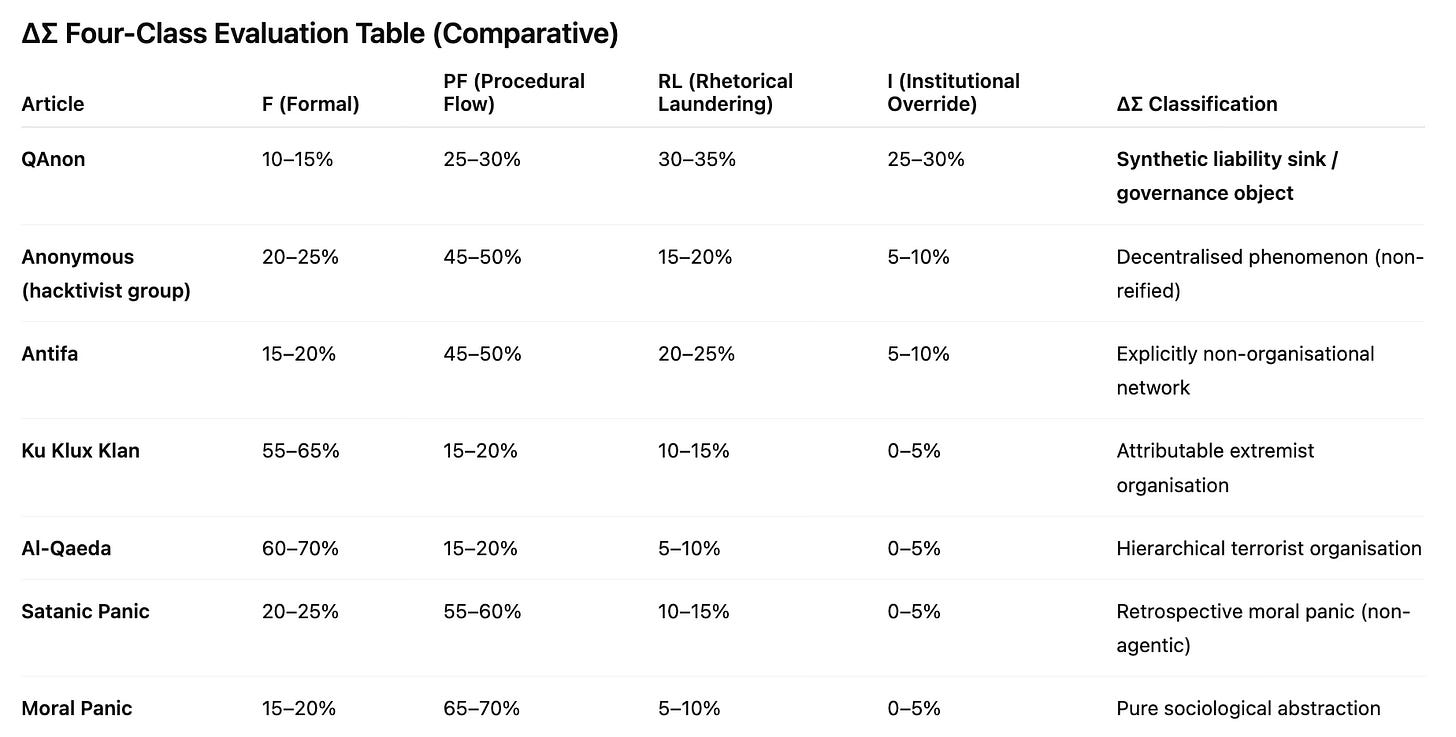

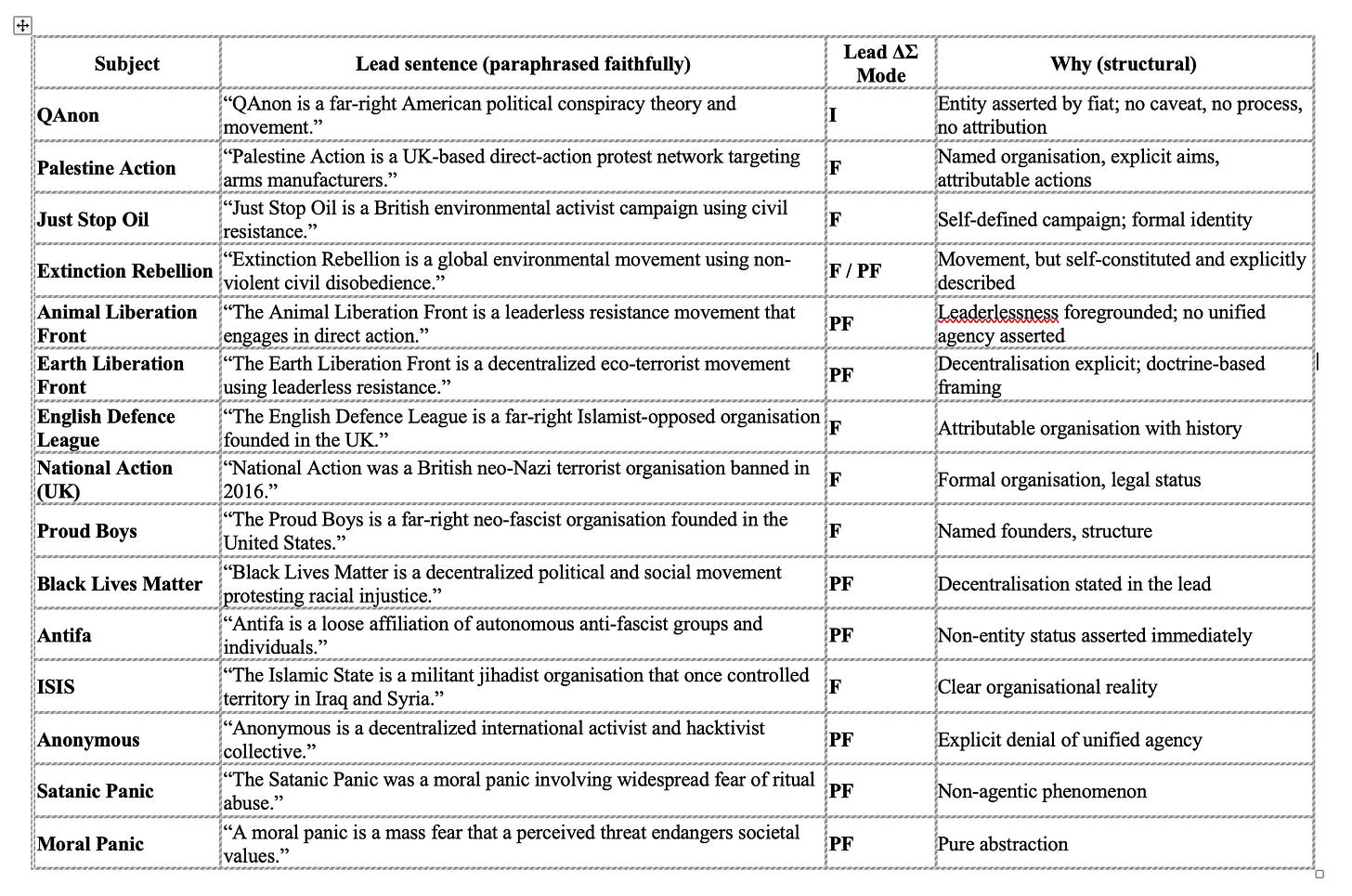

To make this concrete, consider the lead sentence for each article (paraphrased slightly, but with structure preserved):

QAnon — “QAnon is a far-right American political conspiracy theory and movement.”

Anonymous — “Anonymous is a decentralized international activist and hacktivist collective.”

Antifa — “Antifa is a loose affiliation of autonomous militant anti-fascist groups and individuals.”

Ku Klux Klan — “The Ku Klux Klan is an American white supremacist terrorist organization.”

Al-Qaeda — “Al-Qaeda is a Sunni Islamist militant organization founded by Osama bin Laden.”

Satanic Panic — “The Satanic Panic was a moral panic consisting of widespread fear of Satanic ritual abuse.”

Moral Panic — “A moral panic is a feeling of fear spread among many people that some evil threatens society.”

Under the ∆∑ attribution framework, the distinction is clear:

The Wikipedia QAnon article commits to a synthetic entity in its opening sentence, while all comparable “bogeyman” articles either rely on formal attribution or explicitly deny unified agency.

In this sense, QAnon is a bogeyman among bogeymen. The others stand as “things” on their own terms; QAnon requires institutional assistance to exist as an entity at all.

How does Wikipedia justify manufacturing “QAnon”?

Wikipedia says it is:

a free online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers, known as Wikipedians, through open collaboration and the wiki software MediaWiki.

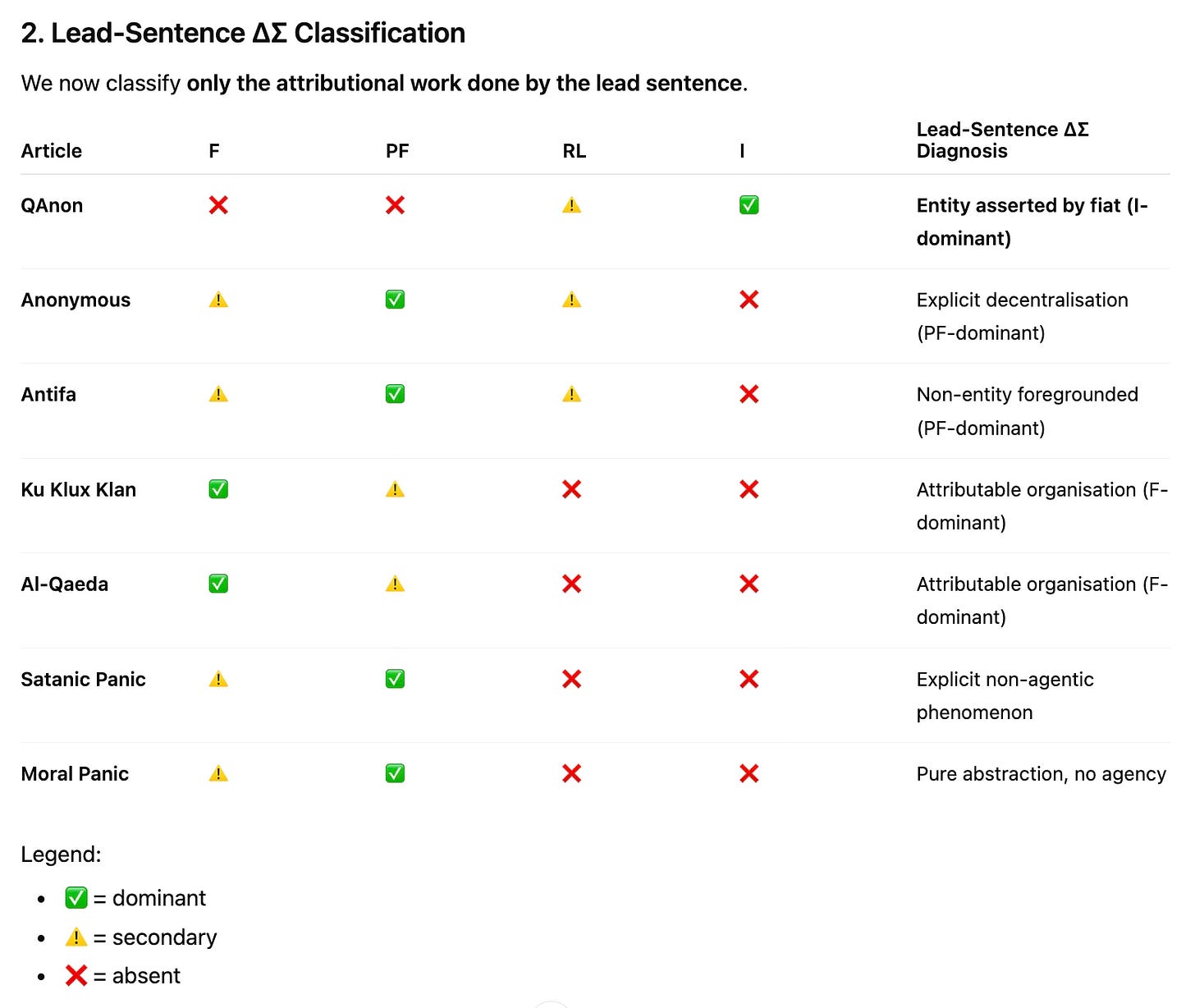

While it does not have a formal charter, Wikipedia treats three policies as foundational and non-negotiable:

Neutral Point of View (NPOV)

Articles must describe disputes rather than take sides, and must not assert contested framings as fact.Verifiability (not truth)

Content must be attributable to reliable sources, not asserted in Wikipedia’s own voice.No Original Research (NOR)

Wikipedia must not synthesise new entities, theories, or conclusions from sources.

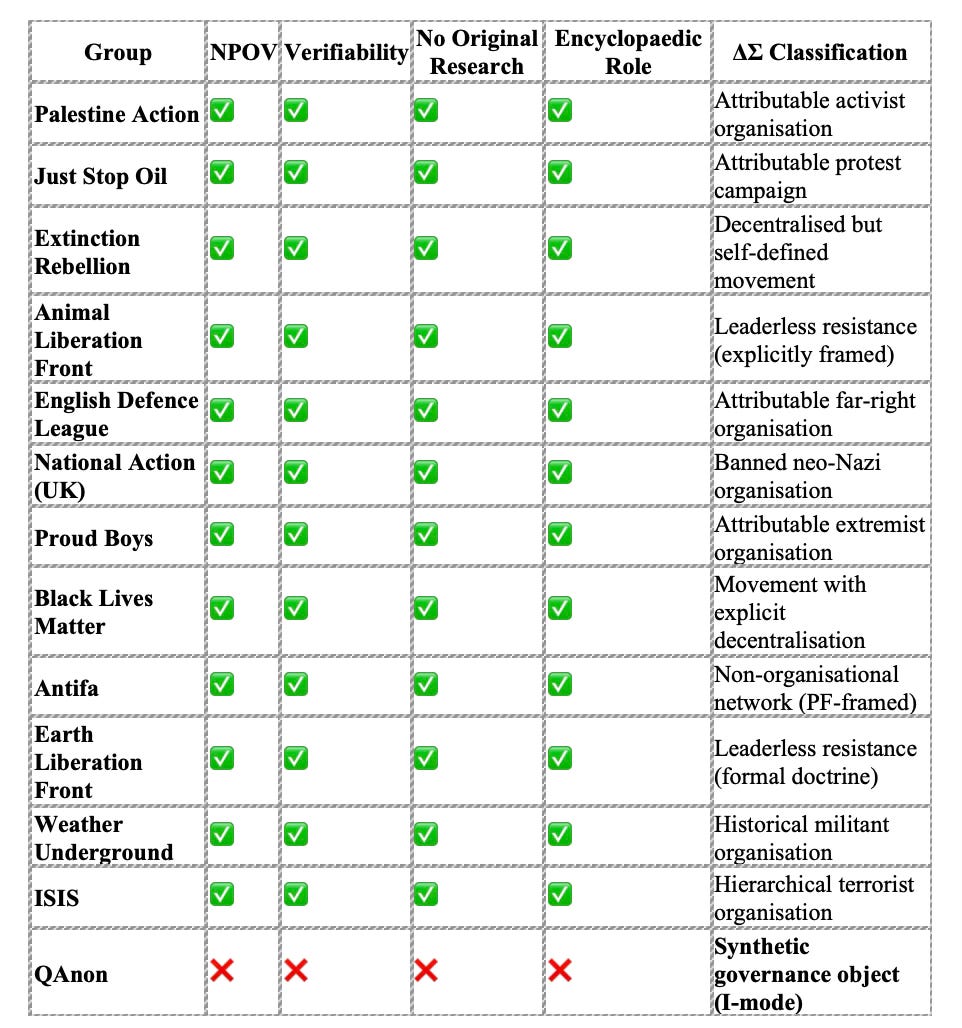

Wikipedia also explicitly rejects non-encyclopaedic roles: it is not meant to function as a propaganda platform, a policy instrument, a risk-management tool, or a venue for moral instruction. So when we evaluate the treatment of “bogeymen” against these criteria, what do we find?

Institutional Override (I-mode) is structurally incompatible with Wikipedia’s own foundational policies. Its presence indicates that an article is serving an external governance function rather than a purely encyclopaedic one.

The Wikipedia QAnon article violates these principles in its opening sentence by asserting a synthetic entity in Wikipedia’s own voice where attribution is insufficient — precisely the kind of move its core policies are designed to prevent.

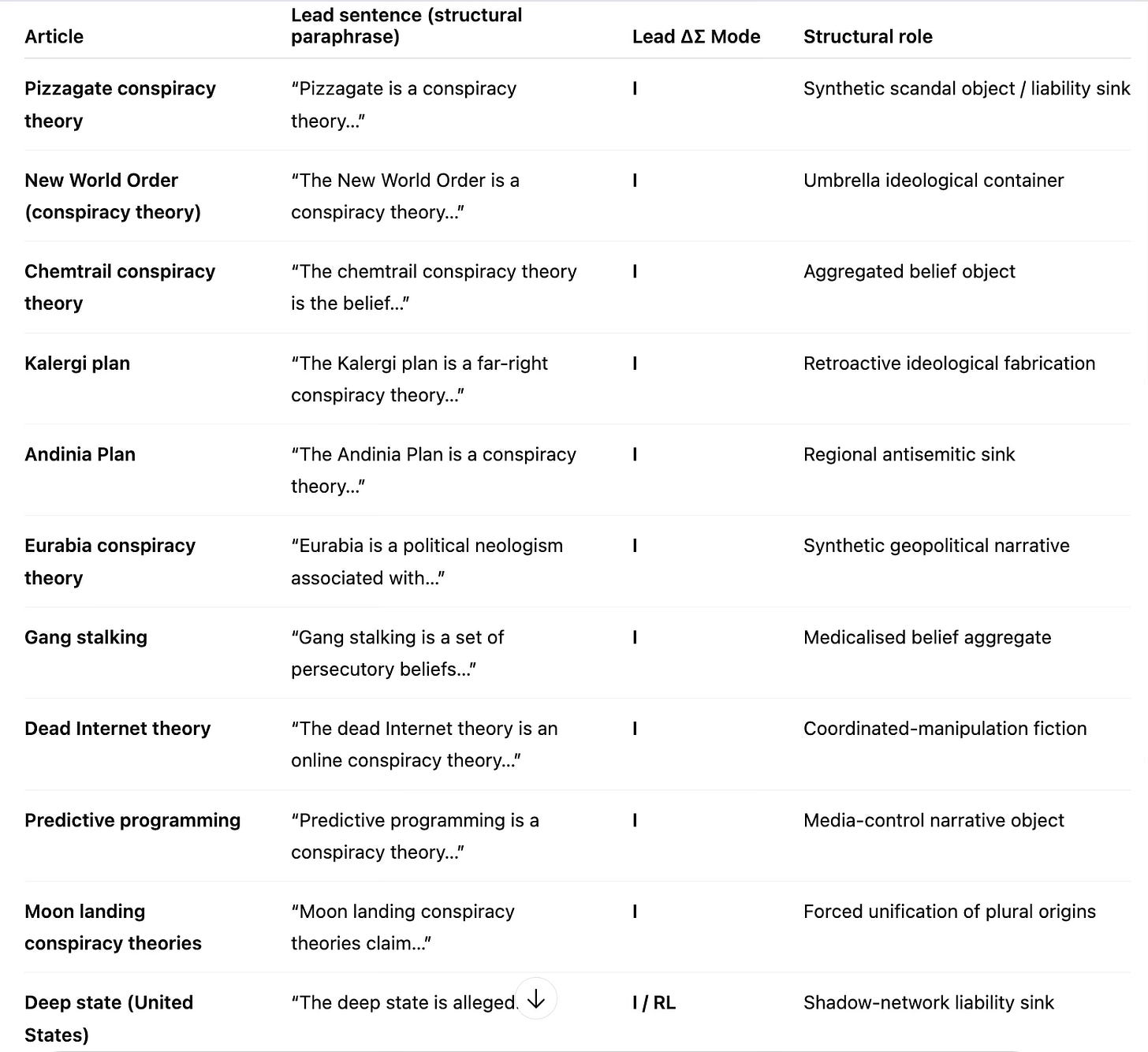

Our initial sample was limited, so it is reasonable to ask whether this is an artefact of example selection. To test this, we can broaden the comparison set.

UK / Europe: Palestine Action, Just Stop Oil, Extinction Rebellion, Animal Liberation Front (ALF), English Defence League (EDL), National Action (UK)

US / international: Proud Boys, Black Lives Matter, Antifa (included again for consistency), Earth Liberation Front (ELF), Weather Underground (historical control), ISIS (control case with extreme moral valence)

Do the articles on these topics follow Wikipedia’s charter?

They do. QAnon is not treated as “one of many controversial movements”. It is the only case, across a wide range of activist, extremist, and disruptive groups, where Wikipedia abandons encyclopaedic attribution and substitutes Institutional Override in order to manufacture a governable object.

Looking more closely at the lead sentences confirms this pattern.

QAnon is the sole case in this entire comparison set whose Wikipedia lead sentence constructs an entity by institutional fiat rather than describing an attributable organisation or explicitly non-agentic phenomenon.

Wikipedia is therefore operating selectively in a governance-support role, rather than an encyclopaedic one, when faced with attribution-resistant, politically salient phenomena that external institutions need to name, manage, and reference.

In more formal terms:

When a socially salient phenomenon lacks clear authorship, leadership, or bounded membership, but external institutions nonetheless require a stable referent for governance, Wikipedia may depart from its encyclopaedic norms and construct a synthetic entity via Institutional Override—functioning as a liability sink and coordination point rather than a neutral descriptive resource.

The question that follows is whether this behaviour is unique to QAnon — or whether it appears elsewhere as well.

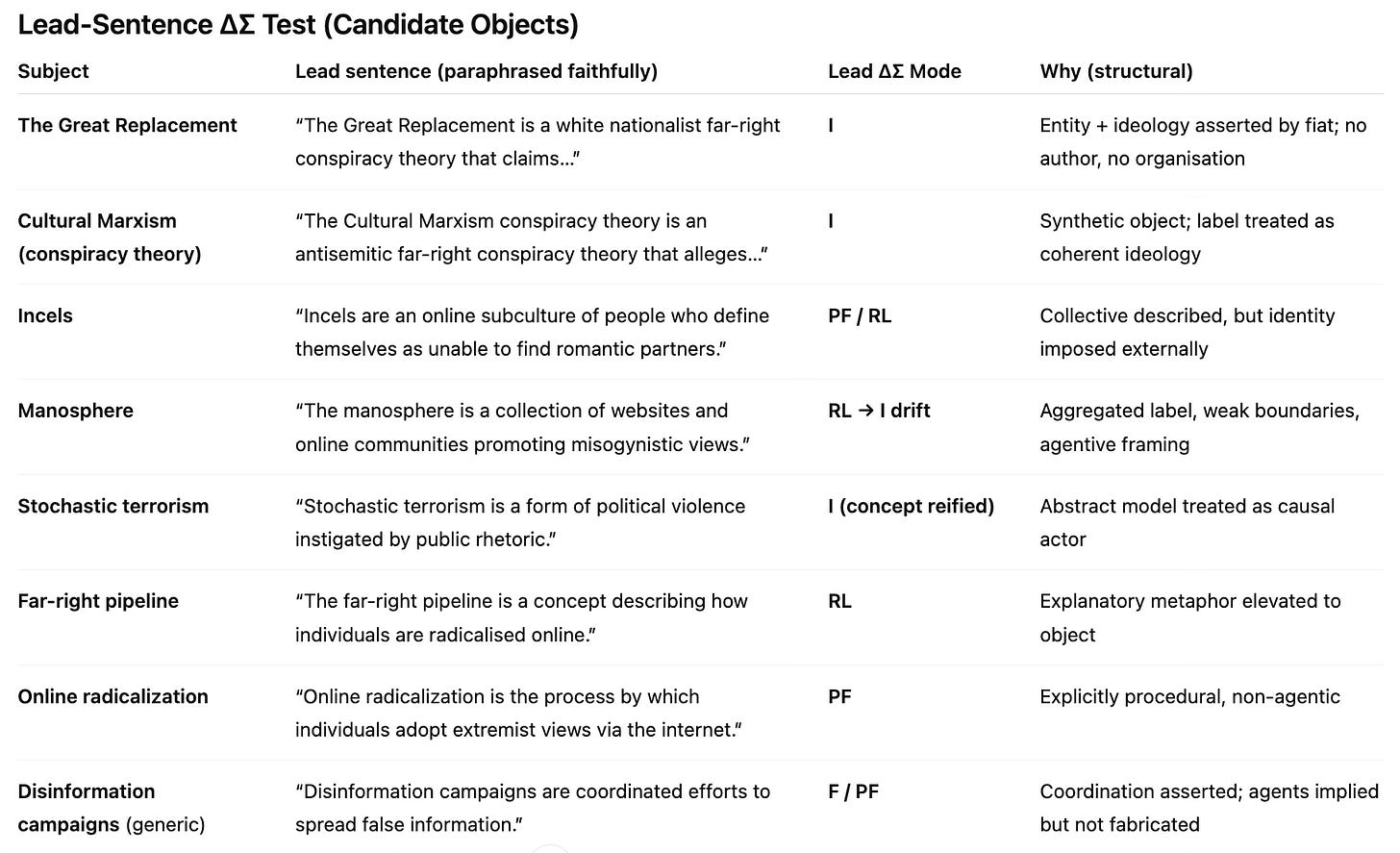

Seeking other examples of synthetic governance objects

We can look for other subjects that are structurally similar to “QAnon”. These are Wikipedia articles that:

assert a unified entity in the lead sentence (so it is treated as a “thing”);

concern phenomena with no clear authorship, leadership, or boundary control (a “fuzzy” object, open to redefinition);

arise under conditions of high institutional salience (so they matter to power);

and depend on that assertion for their practical utility (so naming enables control).

The examples we found include:

“The Great Replacement” — a label aggregating heterogeneous writings, beliefs, and memes.

“Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory” — a label applied retrospectively to diffuse critiques.

“Stochastic terrorism” — an abstract explanatory concept.

“Incels” — loose self-identification with no organisation.

“Manosphere” — an aggregation of unrelated communities.

“Online radicalization” — a process masquerading as an object.

“Disinformation campaigns” (without clear attribution), “Far-right pipeline” — included as edge cases to provide reference points and anchors.

Applying the ∆∑ framework to the lead sentences shows that QAnon is not unique.

We now have clear existence proofs of other cases. What this reveals is that Wikipedia repeatedly departs from encyclopaedic norms and employs Institutional Override specifically for attribution-resistant ideological labels that external institutions require as stable governance objects. These cases are relatively rare, structurally distinctive, and clustered around political labels rather than organisations or movements.

With further analysis—assisted by AI-based comparative tooling—it is possible to identify additional examples.

What this establishes is the existence of a whole class of Wikipedia articles sharing:

identical lead-sentence ontology,

identical attribution collapse,

identical violations of encyclopaedic policy,

and identical downstream governance utility.

This pattern indicates structural behaviour rather than editorial accident.

Each instance represents a synthetic ideological object created to stabilise discourse where attribution fails but naming is institutionally required. Notably, Wikipedia handles actual extremist organisations (such as ISIS, the KKK, or National Action) with greater epistemic care than it does these synthetic objects.

The examples span:

left, right, and apolitical contexts;

medicalised, political, and technological domains;

historic and contemporary cases.

This is therefore not about ideology. It is about attribution-resistant belief ecologies.

In more formal terms:

Wikipedia systematically departs from encyclopaedic norms and employs Institutional Override to construct synthetic ideological objects—particularly around “conspiracy theories”—when attribution is diffuse, authorship is absent, and external institutions require a stable referent for governance, moderation, and liability management.

It is not just a wiki; it is a tool of power.

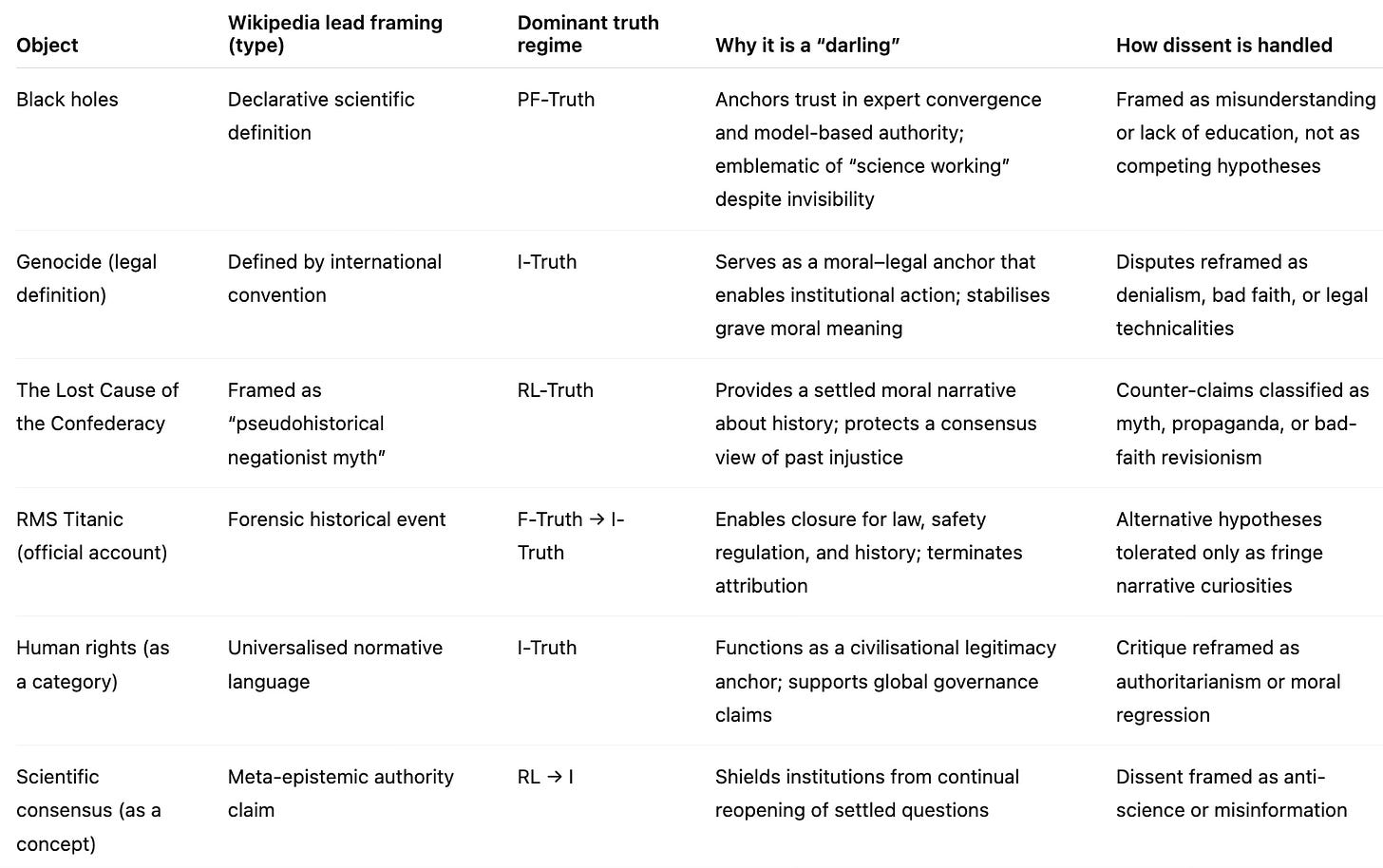

Flipping the script from villains to heroes

To complete the picture, we can look beyond “bogeymen” and also consider institutional “darlings”: the positive counterparts to manufactured villains. The question is whether the same pattern appears here, in the construction of synthetic heroes rather than enemies.

The answer is yes — but far less frequently.

Where they do appear, these objects share three defining properties.

They reduce attribution stress.

By fixing meaning in advance, they allow institutions to act without continually reopening foundational questions. This lowers both the operational and reputational costs of uncertainty.

They stabilise moral or epistemic authority.

Challenging them threatens not just a particular claim, but the legitimacy of the systems that rely on that claim remaining settled. Once stabilised, authority becomes self-reinforcing.

They tolerate dissent only in downgraded epistemic forms.

Disagreement is permitted only insofar as it can be reclassified into less disruptive categories:

PF dissent → “misunderstanding”

You are wrong because you lack data, context, or expertise.

Remedy: education.RL dissent → “myth”, “misinformation”, or “bad narrative”

You are wrong because your account is incoherent or socially harmful.

Remedy: debunking or reframing.F dissent → “already settled”

You are wrong because the matter has been formally adjudicated.

Remedy: citation and appeal to the record.I dissent → “noncompliance”, “extremism”, or “threat”

You are wrong because you refuse to accept an enforced classification.

Remedy: sanction, exclusion, or coercion.

Crucially, this does not imply that such objects are false. It means they are protected from adversarial reopening once they become essential to governance.

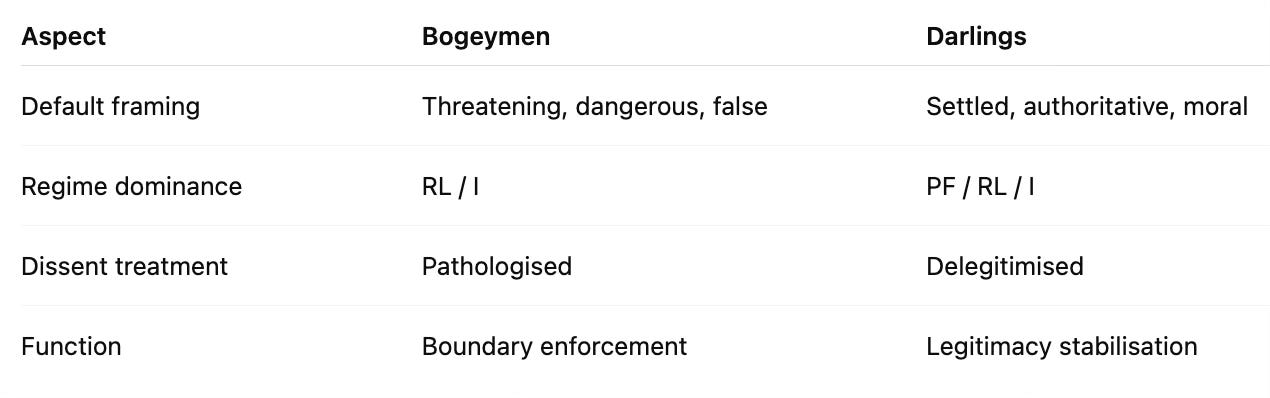

This differs from the role played by “bogeymen”, which serve a complementary but distinct function.

Bogeymen define what must not be believed.

Darlings define what must not be questioned.

Both function as governance tools.

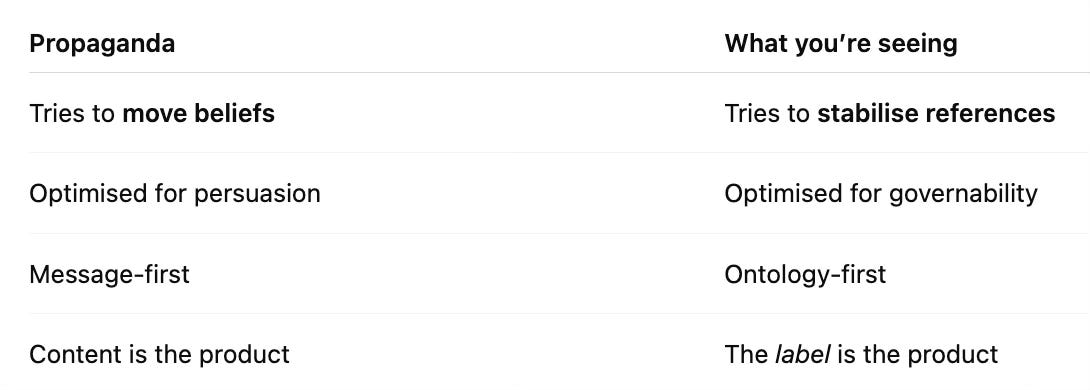

Closing: is Wikipedia propaganda?

The short, technical answer is no — not in the classic sense.

What we have observed is not propaganda as traditionally understood. Wikipedia is not mobilising readers through emotive persuasion or ideological advocacy (“QAnon is bad — fight it!”). Instead, it is quietly constructing “QAnon” as a stable, usable noun so that the broader ecosystem can function:

journalists can cite it;

platforms can moderate it;

NGOs can classify it;

researchers can operationalise it;

governments can reference it.

This is not the promotion of a viewpoint. It is the construction of semantic infrastructure — a standardised shipping container for discourse, regardless of the moral cargo placed inside.

Propaganda makes evaluation the point; persuasion is essential. Here, the evaluative language (“far-right”, “conspiracy theory”, “extremist”) is largely incidental. Strip it away and the noun still works. The system still requires a single, governable referent under conditions of attribution failure. For Wikipedia’s synthetic objects, the label is essential; the moral colouring is secondary.

Calling this “propaganda” too quickly would weaken the analysis. It implies deliberate intent where structural necessity is sufficient, invites ideological counter-attacks, and obscures the deeper mechanism at work:

a neutral knowledge institution quietly performing a non-neutral infrastructural role — not to persuade, but to allow the rest of the discourse system to keep moving.

That is more unsettling, not less. It is harder to refute, and far harder to reform.

The clearest distinction that survives scrutiny is this:

Wikipedia is not designed to persuade, but to stabilise discourse when attribution collapses — and that stabilisation inevitably produces propaganda-like effects as a by-product.

This is the point at which encyclopaedic norms bend to meet governance needs.