The fatal dishonesty of "ghost courts"

HMCTS's two-faced stance lacks moral integrity and damages the rule of law

I cannot now recall where I first encountered it, but one of my early “aha!” moments about the nature of totalitarian systems was this: the absurdity of bureaucratic rules is not accidental. When everyone knows the system is nonsense, yet they still comply, the result is a ritual of humiliation that erodes conscience and autonomy.

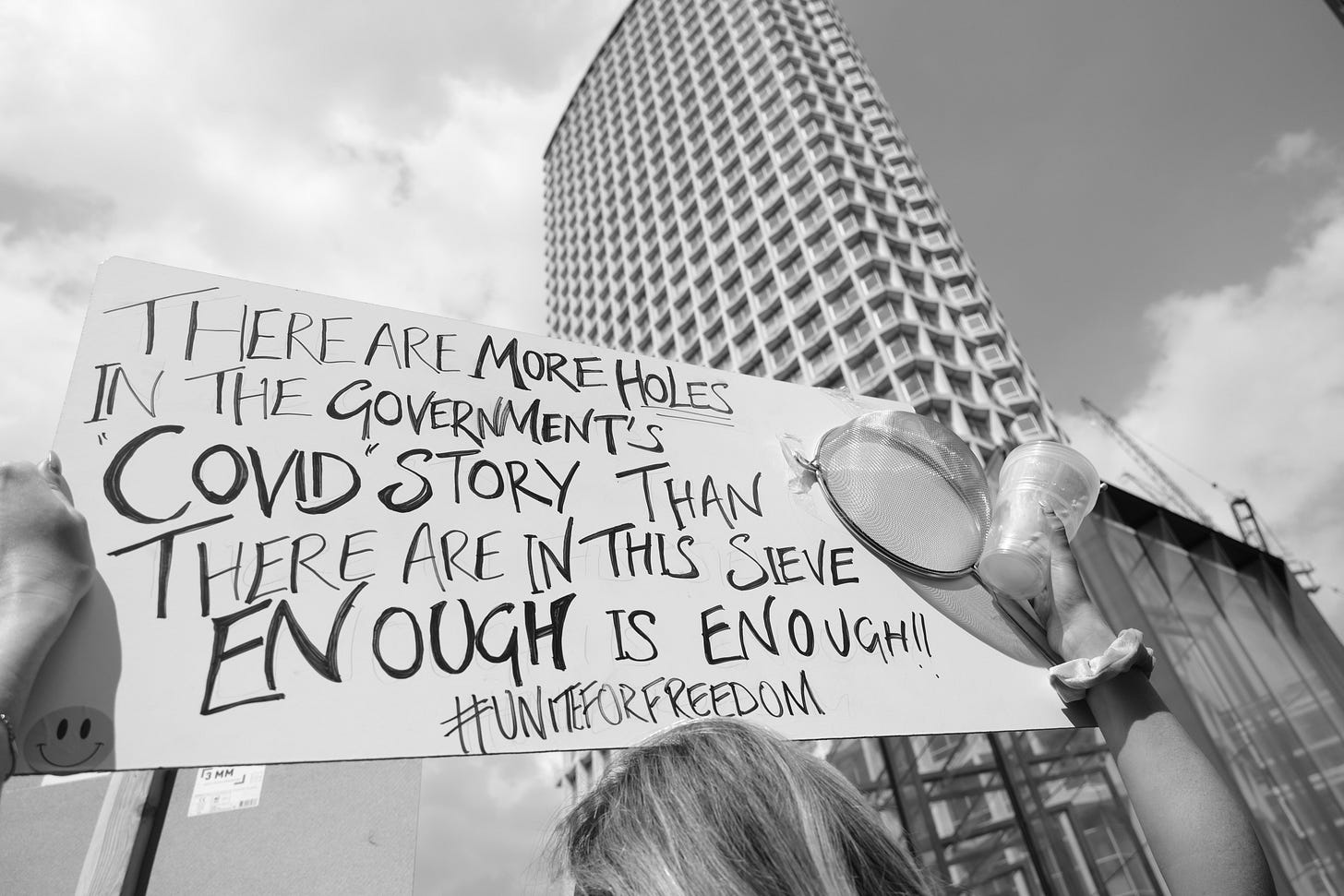

This dynamic resurfaced during the Covid-19 period, when measures such as mask mandates and selective distancing rules were presented in ways that defied internal coherence. Compliance was secured not by rationality, but by collective acceptance of contradictions.

Misrepresentation of authority in criminal process

As I examine what I call the “ghost court” phenomenon, the same abusive pattern emerges. Citizens are told that “everything is lawful,” and that even where defects exist, there is a statutory saving clause to cure them. Yet at the very point where the State claims coercive power over the individual — the heading of the summons — the authority is often misrepresented.

If the words “Magistrates’ Court” appear on the first line, the ordinary person is entitled to assume that is the statutory court seised of their case. If, in fact, that label is an internal brand or IT construct, then the appearance of authority is misleading. Article 6 ECHR requires that a court be “established by law” and that process be clear and intelligible. This is ordinary common sense.

Administrative drift

Over the past twenty years, local courts have been reorganised. Petty Sessional Divisions gave way to Local Justice Areas (LJAs). HM Courts and Tribunals Service then promoted synthetic labels derived from LJAs into the “headline” on summonses. These were sometimes merged with internal location codes (e.g., “North and West Cumbria Magistrates’ Court (1752)”).

The practical effect was to demote traditional courthouse names (e.g., Carlisle Magistrates’ Court) into mere “venues,” while elevating administrative composites into the status of “the court.” Yet in law, the court remains the justices in session at a proper venue, not an IT label. The difference is everything, as with jurisdiction you cannot have competing claims to authority.

Jurisdiction as a two-way bridge

Jurisdiction is a bridge that must be crossable in both directions. The State must be able to reach out to an individual and compel participation in the legal process. But the individual must equally be able to identify the lawful authority by which that demand is made.

When the summons uses multiple or conflicting names, or substitutes a non-existent “ghost court” for a statutory magistrates’ court office, the bridge collapses. The individual cannot verify the warrant of authority. Jurisdiction is lost at the threshold, because the gateway to compulsion is mis-specified.

The minimum standard

The technical legal minimum for a valid summons is straightforward:

The defendant’s name and address.

The particulars of the alleged offence.

The time and place to attend.

The name and address of the issuing magistrates’ court office.

This requirement is not cosmetic. It is the first claim of lawful authority. Embellishments such as the Crown crest are unobjectionable,. But when HMCTS substitutes an LJA alias plus IT code as if it were a statutory court, the summons risks becoming unintelligible — and hence unlawful, as well as morally ungrounded.

Consequences of court misrepresentation

This drift has consequences across the enforcement chain. DVLA records now reference synthetic “ghost courts,” while HMCTS enforcement notices sometimes omit the court entirely. Citizens receive no sealed orders bearing the name of a real court of record.

If all were straightforward, HMCTS could explain and justify the labels openly. The very fact that stonewalling and retrospective justifications are needed shows that the practice rests on shaky legal ground. The crack in the foundation is right to the bedrock — the covenant between the people and State is breached.

The “excuses” reveal the breakdown

Paradoxically, it is the reasoning of HMCTS itself, in a quasi-defence brief to its own legal advisers, that reveals how far the system has drifted. The standard lines run as follows:

Claim: Even if every summons names a non-statutory “court”, all defects can be cured retrospectively under section 123 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980.

Response: This confuses a local defect (like a spelling error or torn paper) with a jurisdictional nullity. Section 123 was meant to save cases from trivial slips, not to validate systemic misrepresentation. Parliament cannot by fiat make a non-existent court into a lawful one; jurisdictional error is not curable.

Claim: Jurisdiction rests on the information or written charge, not the summons, so defects in the summons are irrelevant.

Response: The summons is not a disposable mechanism; it is the citizen’s notice of compulsion. ECHR Article 6 requires it to be intelligible and precise. If the summons misrepresents the court, the bridge of jurisdiction is broken at the threshold.

Claim: Court names have “no legal significance,” so misnaming does not matter.

Response: The criminal procedure rules require the court to be named. The heading is the first and main claim of authority. Misrepresentation there is fatal; “surplusage” doctrine cannot apply to the gateway of jurisdiction.

Claim: Local Justice Areas are administrative only, so their omission or misstatement has no effect.

Response: HMCTS cannot have it both ways: internally LJAs are “administrative,” but externally they are presented as courts to secure public compliance. That inconsistency itself is a form of misrepresentation and dishonesty.

Claim: Summons form rules are minimal, so extra words or labels make no difference.

Response: True, only the essentials matter — but among those essentials is the court name. If that is wrong, the summons fails. This is not like leaving off a crest or using the wrong font.

Claim: Magistrates can sit anywhere in England and Wales under a single commission, so assignment is flexible.

Response: Elastic deployment does not authorise fictive labels. Justices may be redeployed, but the issuing court office must still be real and identifiable. Administrative convenience cannot substitute for juridical authority.

Claim: Case law shows errors don’t remove jurisdiction once the defendant appears.

Response: That applies to procedural defects after a real court has been seised. It does not apply where the summons names a court that never existed. A non-entity cannot acquire jurisdiction, no matter who attends.

The legitimacy time bomb is armed

The High Court may yet decide to endorse a manifestly false claim to authority in order to salvage the Single Justice Procedure and shield HMCTS from existential humiliation. If so, it will be pronouncing the legal equivalent of: “there is no ghost mural on the side of the Royal Courts of Justice.” This recalls the recent Banksy episode, where officialdom disclaimed what everyone could see with their own eyes. The cost of sustaining the fiction is not short-term embarrassment, but the steady erosion of legitimacy.

The conduct I have encountered demonstrates that something is being concealed. Freedom of Information requests are late, evasive, or contradictory. The prosecution advances one theory of jurisdiction, the bench another, and the clerk yet another. Established statutory mechanisms for testing jurisdiction are suppressed. Complaints vanish into administrative limbo. Pre-action protocol letters are ignored, again and again. This is not the conduct of a system confident in its position, but one scrambling to avoid scrutiny.

The descent into judicial ridicule

If the supervisory court rules that English law tolerates misrepresentation in court names, and that jurisdiction can still be asserted through such devices, the reputational damage will be catastrophic. Britain would be seen to fall below the very standards it demands of others, and would invite the same criticisms it directs at Turkey, Ukraine, or Georgia for defective judicial practice. Authoritarian states in Moscow and Beijing will be handed a propaganda gift: “Look, even Britain runs ghost courts.” This is not just academic; it risks formal scrutiny from UN Special Rapporteurs on judicial independence and arbitrary detention.

The danger extends beyond the international arena. If HMCTS persists with this practice and the media expose it, mass non-compliance becomes a real possibility. Once the public understands that the court named on the top of a summons is as fictitious as a forged banknote, the moral obligation to attend court or pay fines collapses. The damage would not be confined to the Single Justice Procedure. The integrity of the entire criminal justice system is tainted if fraudulent court names are tolerated. If misrepresentation at the gateway is permitted, then there is no lower bound to the decline.

Truth is the only way out

HMCTS is telling one story to the public, another internally, and acting in ways that align with neither. Court names are presented to the public as if statutory in order to secure compliance, while staff are told they are meaningless administrative labels, and all attempts to scrutinise the practice are blocked. This double standard cannot be dismissed as a technicality. Court names are not decorative; they are the foundational claim of lawful authority on a summons.

HMCTS has been placed in an impossible position by Parliament, which bears ultimate responsibility for the mess. In striving to meet impossible targets under poorly framed legislation, HMCTS has overstepped and assumed powers that belong to Parliament — effectively creating forged courts. While the administrative pressures explain how this drift occurred, they do not excuse it.

In a functioning constitutional monarchy, this would be the moment for the Crown to intervene and insist on truth, however costly or painful. Failing that, it falls to the public to shine a light on the duplicity. Only open acknowledgement of the problem — and reform at source — can preserve legitimacy. Without truth, the criminal justice system remains tainted by a practice that undermines both the law and the trust on which it depends.

I keep getting letters from TV license as I cancelled it some years back.

It's addressed to "the occupier" I stick a label with there address on it over the window in the envelope and sent it back to the fictional realm that created it.

Vampire's are real and take many forms, I would include our governmental in the list🧛♂️

Don't let them in🙏🤝

Administrative convenience cannot substitute for juridical authority.

There is case law about this …