The human cost of a religious Christmas

A chance encounter at Durham cathedral reveals a darker side to church life

Back in the summer I attended court in Durham, and then went on a tourist trip with an overseas companion to visit the famous cathedral that looms above the town, nestled in a loop of the River Wear. Events in my personal world delayed me telling a story from that day, but a discussion about attending a Christmas mass at the same venue prompted me to belatedly share what happened with you. A short conversation with an old man said a very great deal about the nature of the modern religious church and its revealed spirit.

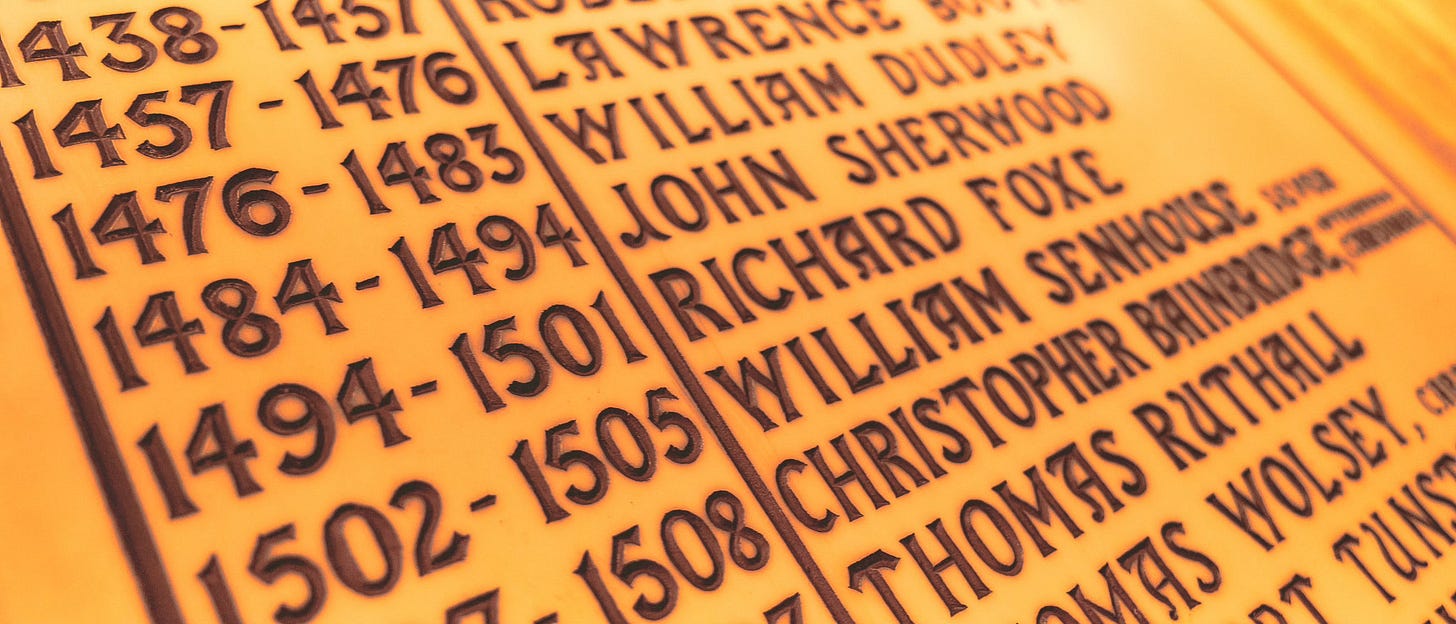

As context, this is the Church of England we are talking about, which may occupy these ancient buildings, but is likely unrecognisable to those who erected these edifices. After all, the clue is in the name — England being a political concept, not a theological one — and the church’s purpose being aligned to the British establishment’s institutions and interests. (Hint: it’s money, not righteousness, they worship.)

When passing through these places, attention to detail often exposes the subtext of the place, which cannot be explicitly on display.

You are meant to pray through Jesus, not to Jesus, but confusing The Way To Salvation with Its Perfected Ending is standard church confusion.

Donate as much as you can afford, without bounds? Really? Why not ask people to bring candles? This would remove the middleman of the fiat moneychanger. But that might not go down too well when you have clerical salaries and pensions to pay!

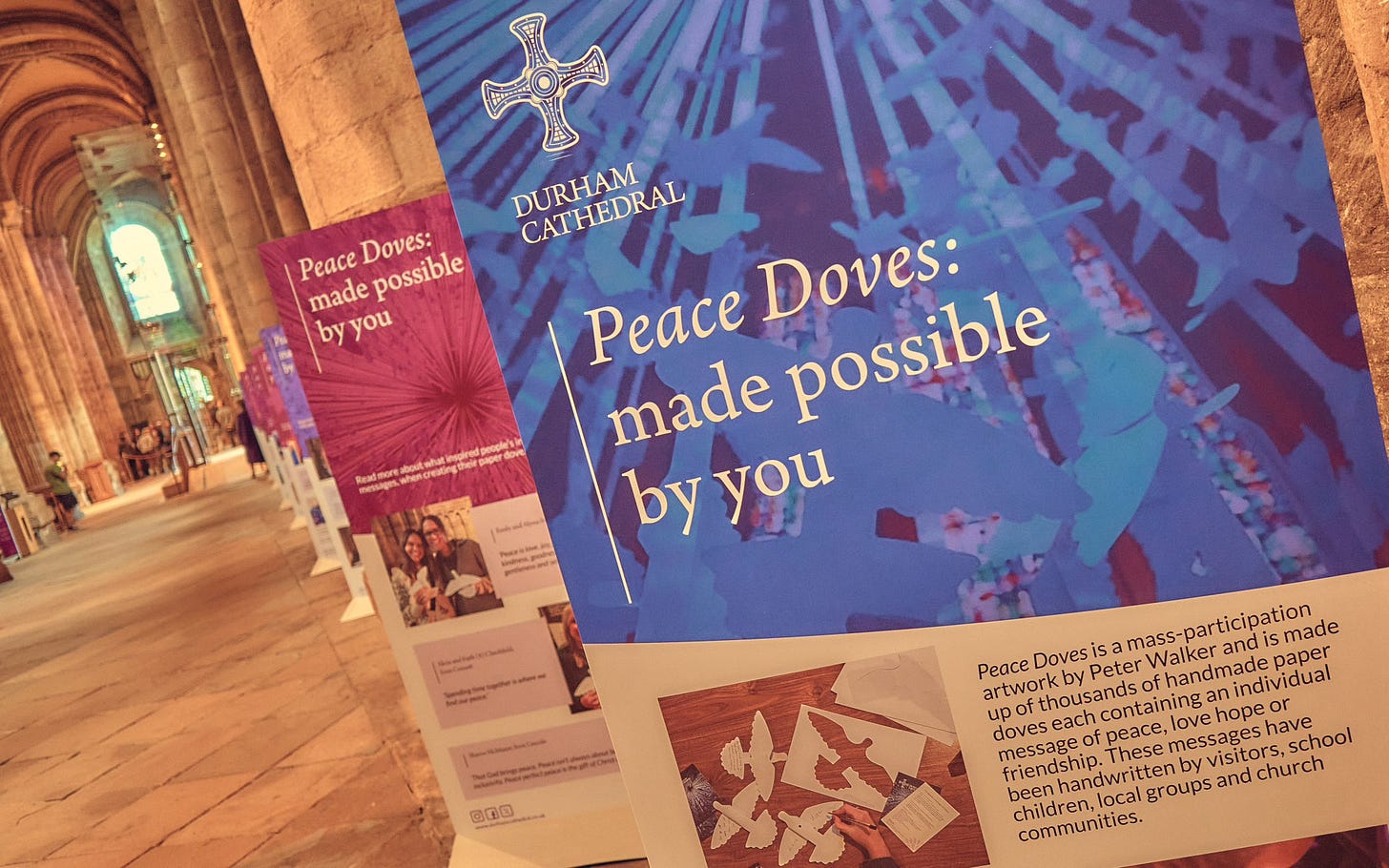

Anyhow, the centrepiece of the cathedral on this occasion was a temporary art exhibit.

Note that it is “church communities” in the blurb — which can be read as being in contrast to the actual purpose of the church, which is a singular community aligned to a sole divine spirit. The institutional church sells Jesus as an icon of peace, and itself as a peaceful enterprise, yet Jesus himself did not make this claim, and proposed quite the opposite:

Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law. And a person’s enemies will be those of his own household. Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. And whoever does not take his cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.

— Matthew 10:34-39

This divergence of what the claimed purpose of the church is, and what it actually does, sets up the story nicely.

Many sat around to contemplate the work. I and my companion attracted the interest of one of the caped stewards, a man advanced in years. He came over as being a gentle soul, if a little sad at the state of the world. His story was that he had come to the church as a chorister when a young boy during WW2. My companion asked what he made of the art installation, and he did not seem very impressed by the assortment of paperwork hanging from the ceiling.

She then asked what impression the magnificent ancient building had made on him when he first entered as a child. Rather than answer the question, he instead told of his sadness. Even though his family was only a few miles away, being in the cathedral choir meant he had to stay at the church. He would quietly sob into his blanket at night, being lonely and homesick. He only got to see his parents once a week.

The worst time of year was Christmas, as there were extra services for the public on Christmas Day, yet he was denied the opportunity to enjoy that time having a meal with his own family. He was essentially a servant to the religious church, when the church was meant to be a servant to him, a vulnerable and innocent child.

The very foundation of Christianity is freedom — from personal strife, national war, and corrupt legalism. Instead of liberating this child, he has been enslaved. To this very day he is in nonstop service to the religious order, whose fundamental survival interests are the support of the political body, not the ending of worldly ways.

Times do change, and maybe today’s choirboys have a superior family connection, and better pastoral care. Yet the persistent moral of the story is hard to ignore. The institutional church is configured to glorify itself, and its loyalist adherents, in ways that contradict gospel teaching, and use children as tools to that end. I have many other visual anecdotes of wokeness in the church which I can share separately.

My own relationship to this place changed with this brief conversation. I saw a hidden human cost of Christmas carols, which is rarely shared in this candid way. Once seen, it cannot be unseen. Maybe our churches are spiritually inverted, treating children as peripheral, rather than figural to their mission? A rather sobering thought for such a spectacular structure.

We decided to skip the Christmas Eve carols and midnight mass — it didn’t sit right.

Beautiful, sad, insightful. Thank you Martin.

God bless.

❤️

Although the building is pleasing to the eye and a wonder to marvel at (thanks to your keen sense of artistry), I sense the absence of spirit through your lens and observations. I gave Christmas a rest this year. No tree. No wreaths. No cards. No gifts. After everything we have been put through psyop after psyop, lies and more lies, persecution from the corporate state-of-mind, social media attacks and shadow banning, I simply could not carry on as usual. I’m just a wet blanket, I suppose. Disillusioned with the whole thing. But somehow I feel free. Lonely, but free. It’s gonna take awhile to adjust, but I will. Unlike that elderly gentleman, I am less enslaved today. As always, mahalo Martin, for your brilliant insights!